Week 11

Week 11: Tuesday, January 12, 2016

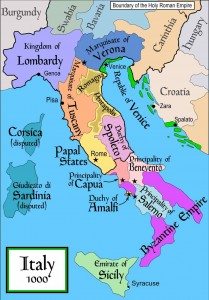

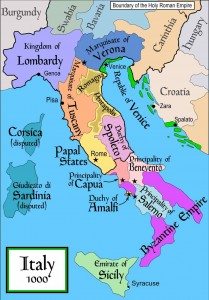

Italy in the Year 1000

Europe approached the year 1000 AD with fear and foreboding at the same time that it experienced the most extraordinary leap forward. It feared the chronological marker. For one thousand years, Christians had awaited the Last Judgement, the Revelation, the Final Days. And the approaching year seemed obvious as the possible approaching end of all things. But on the hand, in the secular world, in the world of trade and economic expansion, Europe had not seen times like these since the Fall of Rome. So what was one to think? was everything coming to an end? Or was everything about to get better? The year 1000 is a fascinating moment in European and Italian history. In continental Europe, the Holy Roman Empire established itself as the most powerful state. Otto III made a pilgrimage from Rome to Aachen, stopping at Regensburg, Meissen, Magdeburg, and Gniezno. In Rome, he built the basilica of San Bartolomeo all'Isola, to host the relics of St. Bartholomew. In France, Robert II, the son of Hugh Capet, was the first of the Capetian kings. The Byzantine Empire under the Macedonian dynasty was sorely pressed by the ongoing Muslim conquests, losing many of its eastern territories in the Byzantine–Arab wars (780–1180). At the same time, Byzantium was instrumental in the Christianization of the Ukraine and of other medieval Slavic states. In Great Britain, a unified kingdom of England had developed out of the various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. In Scandinavia, Christianization was in its early stages, with the Althingi of the Icelandic Commonwealth embracing Christianity in the year 1000. On September 9, King Olaf Tryggvason was defeated by an alliance of his enemies in the Battle of Svolder. Sweyn I established Danish control over part of Norway. Oslo, Norway, was founded in 1000. The papacy during this time was in a period of decline, in retrospect known as the saeculum obscurum ("Dark Age") or "pornocracy" ("rule of harlots"), a state of affairs that would result in the Great Schism later in the 11th century. Hungary was established in 1000 as a Christian state. In the next centuries, the Kingdom of Hungary became the pre-eminent cultural power in the Central European region. On December 25, Stephen I was crowned as the first King of Hungary in Esztergom. Sancho III of Navarre became King of Aragon and Navarre. The Reconquista was gaining some ground, but the southern Iberian peninsula would still be dominated by Islam for centuries to come; Córdoba at this time was the world's largest city with 450,000 inhabitants. (The preceding survey based on Wikipedia article on The Year 1000.)

RECOMMENDED READING:

Robert Lacey,

The Year 1000: What Life Was Like at the Turn of the First Millennium,

Back Bay Books (April 1, 2000),

ISBN 9780316511575

RECOMMENDED READING:

Michele Spike,

Tuscan Countess: The Life and Extraordinary Times of Matilda of Canossa ,

Vendome Press; 1st edition (September 28, 2004),

La Contessa Matilda was the most important person in 11th Century Florence. She led the explosive revival of Florence; she endowed and encouraged the church; she rebuilt the architecture. This biography is the first one we have had in English that is really good and worth recommending.

From Publishers Weekly:

The dramatic life of Matilda of Canossa (1046-1115) could easily be the plot of a Pirandello play: there are papal intrigues, warring medieval factions and even an ill-fated marriage to a hunchback that ends in murder. Spike's marvelous biography of the countess takes on all of these events, and also explains how Matilda became an ardent defender of the lands in the Po Valley, which she considered her birthright. Spike deftly conjures the world of pre-Renaissance Italy, where a woman "passed through her life from father to brother, to husband, to son, as each in his turn acted for her welfare." Many of the men in Matilda's life, however, failed to act in her best interests, and under such conditions, the remarkable young woman flouted the traditions of her male-dominated world and managed to defend her small portion of Italy from Henry IV. Using a staggering amount of new research, Spike peels back layer upon layer of previous myth to render a startling new portrait of the countess. (The author also displays a novelist's talent for detail, exploring the unusual alliance between Matilda and Pope Gregory VII, her ally and lover.) Spike's first-person account of her exhaustive research is one of the book's unexpected pleasures; the modern-day characters she encountered during her hunt provide this engrossing historical chronicle with a richly personal subtext. 40 b/w illus.

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

12

Week 12: Tuesday, January 19, 2016

Italian Art in the Middle Ages: Sculpture

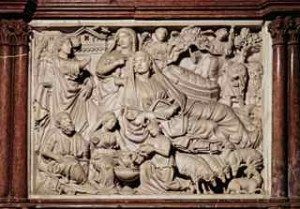

At the right you see Nicola Pisano, Nativiy, Carrara marble, Pisa Baptistry pulpit. Notice Mary and her Roman matron face. Pisano is copying Roman sculpture that is sitting there in Pisa. From 1000 AD to 1300 AD, artists in Europe changed the look of Western art. The change took place with Italian architects, sculptors and painters leading the way. The art of scuplture allows us to follow the transformation without interruption from the Fall of Rome all the way forward to our period, 1000-1300, this Winter Quarter. In Italy alone, there is no permanent interruption in the production of art even in the worst of times. In some periods the production is small, but it still allows us to see the change take place. Italy had one major advantage over other European states: it had the Roman scuptural past sitting all around it. Thus the first hints of Medieval artistic change are visible in cities such as Pisa where the Roman sculptural remains are rich, and local artists such as Nicola Pisano and his son Giovanni Pisano, can lead the way, starting with their own local Roman past. To the right, you see Pisano's Virgin Mary and she will remind you of a Roman matron.

13

Week 13: Tuesday, January 26, 2016

Monasteries

In the seventy-plus years between the last Roman Emperor (476 AD) and the death of Benedict (547 AD), Western Europe created a whole new version of Christianity: monastic Christianity. Born in the years of massive social unrest and political collapse, the new monastic life as it came to be lived in Italy under the leadership of Benedict, appealed to both men and women, rich and poor, young and old. It offered people the opportunity to withdraw from the confusion and to move into a safe space and to join a community of like-minded individuals who welcomed the simplicity of monastic life. The single most important individual in the creation of this new way of life was Benedict of Nursia. We met Benedict in Fall Quarter, and now we want to turn to some of the other great monastic houses that became the most important centers of cultural preservation in all of Europe and especially those in Italy. All these houses can be visited today.

- Monte Cassino, founded 529 (Benedict)

- Lerins, France, founded 410.

- Fulda, Germany, founded 744 by disciple of Boniface.

- Cluny, Burgundy, France, founded 910 (Benedictine)

- Camaldoli, Casentino Italy, founded 1012 by Saint Romuald (Benedictine)

- Vallombrosa, Appenine mountains near Florence, founded 1038 by Florentine nobleman.

PART TWO: Visits to some monasteries.

Saint Catherine's Monastery in Sinai, Egypt is one of the oldest monasteries in the world and was begun in 548 AD. It has been in continuous operation since that date and therefore is one of the oldest continuously occupied monasteries in the world. Its official name being Sacred Monastery of the God-Trodden Mount Sinai, lies on the Sinai Peninsula, at the mouth of a gorge at the foot of Mount Sinai, in the city of Saint Catherine in Egypt's South Sinai Governorate.

14

Week 14: Tuesday, February 2, 2016

Universities

One of the most important contributions to modern culture that comes from the Middle Ages are the universities. The ancient Greek and Roman world did not have universities. They had institutions of higher learning such as Plato's Academy, but they did not have universities. The name of the institution tells you much about what it proposed to do: universities were supposed to bring all knowledge together in one location with many different professors and students from all over the world, all of whom knew Latin, the language of a Medieval university. Two of the most important of the early universities were Italian: the University of Bologna specializing in Law, and the University of Padova (Padua in English) specializing in Medicine. We will discuss their creation and evolution and the role they played in the growth of Medieval Italy. In both Padova and Bologna, the university is the most important institution in the city and has significant political power and influence. A great university could MAKE a city; it could put it on the map! Thus any threat to withdraw and relocate was a potential catastrophe.

RECOMMENDED READING:

Charles Homer Haskins,

The Rise of the Universities ,

Cornell University Press Paperbacks, 1957 (First edition 1924),

ISBN 9780801490156

"The republication of Charles Homer Haskins' The Rise of Universities is cause for celebration among historians of higher education and among medievalists of all disciplines...Haskins' argument is a powerful one: that today's university system is a direct (and immediate) descendent of the collections of scholars who gathered around master teachers in the great cities of Europe during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries...[His] thesis was profound for its time and remains the guiding interpretation of medieval universities."

—Library Quarterly

PART TWO: Pictures

See below the University of Bologna.

15

Week 15: Tuesday, February 9, 2016

The Papacy and the Empire

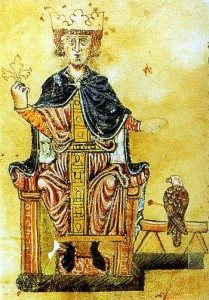

The two most important institutions of the Middle Ages in Europe were the Holy Catholic Church based in Rome and the Holy Roman Empire based in Germany or some other northern country. These two institutions were seen as extending back into past history to the days of Jesus of Nazareth. Both were seen to be eternal and universal. The truth was something different. The Holy Roman Empire was, as Voltaire remarked: "neither Holy nor Roman nor an Empire." But the mythology saw it as an extension of the real Roman Empire. The idea was that the Roman Empire had not declined and ended but had continued in the form of this newer "Holy Roman Empire" founded by Charlemagne and Pope Leo on Christmas Day in the year 800 AD. The Holy Catholic Church in Rome was on more solid ground. It most definitely was Roman. It was a church, an international church. And one would assume it was Holy. In the Medieval vision, these two institutions were partners in the leadership of the whole Christian world. Pope and Emperor, like Charlemagne and Pope Leo, were to work together to bring about peace and unity in the Christian world. In reality, the two fought most of the time. And the rare moments of complete amity between pope and emperor were brief and historically insignificant. But if the two institutions were competitors more than partners, they were, after all, the two institutions in the Middle Ages that mattered the most. This was especially true for Italy; more so for Italy than all the rest of Europe. One of the two institutions was based in the Italian city of Rome. And the second institution was led by the emperor who spent much of his time in Italy too. So whereas Englishmen might view both institutions as distant and unimportant, citizens of Italy most definitely did not.

RECOMMENDED READING:

James Bryce,

The Holy Roman Empire,

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (September 12, 2012) ,

ISBN 1479208523

The Holy Roman Empire was, according to Voltaire, neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire. But it was long-lived, complex, brutal, important, and fascinating, as is evident from the reading of this notable work published in 1871 by the English jurist, historian and politician, James Bryce (1838 to 1922). Bryce concentrates his considerable erudition on the meaning and significance of the empire’s existence rather than on its chronology. This is an essential work for the understanding of western history.

Reader comments on Amazon:

By Lisa C. Philip on July 8, 2013 Format: Paperback." Even though this book was written over one hundred years ago it is still the best book on the topic. Packed with so much information. Highly recommended for anyone interested in the topic."

The Holy Roman Empire was, according to Voltaire, neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire. But it was long-lived, complex, brutal, important, and fascinating, as is evident from the reading of this notable work published in 1871 by the English jurist, historian and politician, James Bryce (1838 to 1922). Bryce concentrates his considerable erudition on the meaning and significance of the empire’s existence rather than on its chronology. This is an essential work for the understanding of western history.

Reader comments on Amazon:

By Lisa C. Philip on July 8, 2013 Format: Paperback." Even though this book was written over one hundred years ago it is still the best book on the topic. Packed with so much information. Highly recommended for anyone interested in the topic."

16

Week 16: Tuesday, February 16, 2016

The Rebirth of the Cities after the Dark Ages

On and around the year 1000 AD the cities of Europe, and especially of Italy, turn a corner. After centuries of war and invasion, almost suddenly, there is peace. Travel on land ad sea is safer. Products move around more easily. People move around more easily. And thus during the Eleventh Century, there is a general resurgence of the European economy and especially that of the cities. The cities grow fast. They expand fast. They build bigger walls. They build huge new cathedrals and huge new city halls like the building on the right, the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. In order to understand this phenomenon we will take one Italian city, Florence, and tell its story from the end of the Roman Empire in the sixth century to the great expansion of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Of all the possible choices for our study, Florence has a major advantage for our study: it was a Roman founded city, it declined as Rome declined, it surged back as all of Europe and Italy rebounded in the eleventh century. Its trajectory reveals exactly the Italian story of so many other cities.

PART TWO: PICTURES

The expansion of Florence in the Middle Ages.

RECOMMENDED READING

This two-volume history of Florence is the best detailed study of Florence ever written. Schevill wrote a masterpiece of well researched narrative history for Florence in 1936 and then it was republished in a Harper Torchbook paperback in 1961. The Harper Torchbook is still out there in used book stores so we have purchased five for our library. But there are still copies left if you want to own one. It is two volumes with the first volume devoted to our period of Medieval History and the second volume on Renaissance Florence. For the Lombards see Medieval Florence (Volume 1) Chapter Three, "Darkness Over Florence."

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU

17

Week 17: Tuesday, February 23, 2016

The Normans in Italy

The Norman conquest of southern Italy spanned most of the 11th and 12th centuries, involving many battles and independent conquerors. Only later were these territories in southern Italy united as the Kingdom of Sicily, which included the island of Sicily, the southern third of the Italian Peninsula (except Benevento, which was briefly held twice), the archipelago of Malta and parts of North Africa. Immigrant Norman brigands acclimatised themselves to the Mezzogiorno as mercenaries in the service of Lombard and Byzantine factions, communicating news swiftly back home about opportunities in the Mediterranean. These groups gathered in several places, establishing fiefdoms and states of their own, uniting and elevating their status to de facto independence within fifty years of their arrival. Unlike the Norman conquest of England (1066), which took a few years after one decisive battle, the conquest of southern Italy was the product of decades and a number of battles, few decisive. Many territories were conquered independently, and only later were unified into a single state. Compared to the conquest of England it was unplanned and disorganised, but equally complete. (From Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING:

John Julius Norwich has written an elegant intelligent book on the Normans in Italy. Many of you enjoyed his book on Byzantium in Fall Quarter.

John Julius Norwich,

The Normans in the South, 1016–1130 (The Normans in Sicily),

Faber and Faber (November 9, 2011),

ISBN 0571259642

About the Author: John Julius Norwich was born in 1929. He joined the British Foreign Service after studying French and Russian at Oxford, and left the service in 1964 to become a writer. He has also worked extensively in radio and television, hosting the popular BBC radio panel game My Word! for several years, and writing and presenting historical documentaries. His many books include an acclaimed Byzantium trilogy.

From Amazon, Most Helpful Customer Reviews 6 of 6 people found the following review helpful a lush narrative history about a uniquely dynamic people By Robert J. Crawford on March 10, 2013 Format: Paperback

"This is an excellent popular history of the Normans - the Viking people that occupied NW France, got feudal recognition and were absorbed into the local culture, and then expanded outward with exceptional dynamism. Theirs was an absolutely remarkable rise, from pillagers to nobility and finally, statesmen and relatively enlightened sovereigns. While their takeover of Britain (the last time the island was invaded, let alone conquered) is well known, their career in the South has received relatively little attention. This wonderfully readable book remedies that in a series of stories that are at once scholarly and fun. When the Normans arrived in southern Italy, they were little more than a mercenary force, indeed thieves. They may have been able to boast they were born of French feudal lords, but they were essentially adventurers with nothing. Their brutality was as remarked upon as their thirst for status and glory. At the time of their arrival in 1016, Italy was uneasily divided between the germanic Lombards, Greeks with ties to Byzantium, and the papacy. Sicily was occupied at the time by various sultans, a culturally rich if unstable mix with Greeks and Latins as well. The Normans, and in particular the family of the Hautevilles, came onto the scene and clawed their way to the top. Robert, dubbed the Guiscard, became a major figure, eventually gaining the title of Duke of Apulia from the Pope, who annointed sovereigns all over western christendom. With his brother Roger, with whom he occasionally warred, he brought order to the South and opened an invasion of Sicily. Though constantly at war with unruly lords sworn to him under feudal obligation, Robert was merciful and tolerant once in power, to the surprise of his critics."

18

Week 18: Tuesday, March 1, 2016

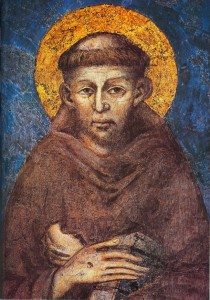

St Francis of Assisi

Saint Francis of Assisi (Italian: San Francesco d'Assisi; born Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, but nicknamed Francesco ("the Frenchman") by his father; 1181/1182 – October 3, 1226) was an Italian Catholic friar and preacher. He founded the men's Order of Friars Minor, the women’s Order of St. Clare, and the Third Order of Saint Francis for men and women not able to live the lives of itinerant preachers, followed by the early members of the Order of Friars Minor, or the monastic lives of the Poor Clares. Francis is one of the most venerated religious figures in history. Francis' father was Pietro di Bernardone, a prosperous silk merchant. Francis lived the high-spirited life typical of a wealthy young man, even fighting as a soldier for Assisi. While going off to war in 1204, Francis had a vision that directed him back to Assisi, where he lost his taste for his worldly life. On a pilgrimage to Rome, he joined the poor in begging at St. Peter's Basilica. The experience moved him to live in poverty. Francis returned home, began preaching on the streets, and soon gathered followers. His Order was authorized by Pope Innocent III in 1210. He then founded the Order of Poor Clares, which became an enclosed religious order for women, as well as the Order of Brothers and Sisters of Penance (commonly called the Third Order). In 1219, he went to Egypt in an attempt to convert the Sultan to put an end to the conflict of the Crusades. By this point, the Franciscan Order had grown to such an extent that its primitive organizational structure was no longer sufficient. He returned to Italy to organize the Order. Once his community was authorized by the Pope, he withdrew increasingly from external affairs. In 1223, Francis arranged for the first Christmas nativity scene. In 1224, he received the stigmata, making him the first recorded person to bear the wounds of Christ's Passion. He died during the evening hours of October 3, 1226, while listening to a reading he had requested of Psalm 142. On July 16, 1228, he was proclaimed a saint by Pope Gregory IX. He is known as the patron saint of animals and the environment, and is one of the two patron saints of Italy (with Catherine of Siena). It is customary for Catholic and Anglican churches to hold ceremonies blessing animals on his feast day of October 4. He is also known for his love of the Eucharist, his sorrow during the Stations of the Cross, and for the creation of the Christmas crèche or Nativity Scene.. (Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU

19

Week 19: Tuesday, March 8, 2016

Italian Art in the Middle Ages: Painting

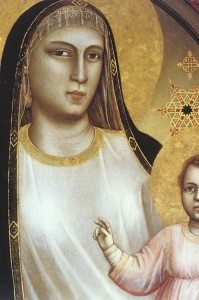

It was in Italy between 1000 AD and 1300 AD that a small number of painters completely changed the way that the art of painting presented the scene of human activity to the eyes of the viewer. Before that time, the Eastern Christian capital of Constantinople had exerted an overwhelming power over the artistic traditions of Christianity. But with the outbreak of the Iconoclastic Controversy which lasted during the 700's and 800's, and the decision of the Eastern Emperor to ban all representations of divine figures in art, suddenly the international art world changed. Artists who had been active in Constantinople rushed to Italy to continue their careers. And by 1000 AD, Rome was beginning to exercize a new power in Christian art. In the next three hundred years, the Greek style as some called it, was overturned and in its place Italian artists labored to develop a whole new native Italian style, a "Latin" style to replace Greek. The earliest efforts in this iconographic revolution took place in Rome but soon it expanded over all of Italy with Florence becoming the most advanced center of painting by the year 1300. The most important name in this new Florentine artistic leadership is Giotto. You see a detail of his Rucellai Madonna to the right. (The painting is in the Uffizi.) Below is a photograph of the Scrovegni Chapel which was painted by Giotto in 1305 to 1310 with stories of Jesus. It would be fair to say that this chapel contains the most revolutionary artistic heritage anywhere in the European world since the days of Rome.

RECOMMENDED READING

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU

20

Week 20: Tuesday, March 15, 2016

The Age of the Cathedrals

By 1300, the economic boom that had begun around 1000 AD was now fully underway and was bearing significant results in the great cities of Italy. Populations were exploding. The city of Florence had to expand its walls three times in a few hundred years. By 1300 Florence contained over 100,000 people. The same was happening in Venice and Milan. Trade was booming. Governments were experimenting with innovative ideas about elections and citizen's rights. The most dramatic evidence of this new culture was to be seen in the various cathedral projects all over Italy. In Milan, Venice, Pisa, Lucca, Siena, and Florence, cities planned massive new cathedral buildings in the center of their city to mark its power and its prestige. The greatest of all these projects was that of Florence. In 1296, the city fathers gathered together to lay the cornerstone of what was to be the largest cathedral in Europe. And the building that emerged did indeed hold that title until Rome decided to build a whole new St Peter's in 1510.

RECOMMENDED READING

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU

All

Week 11: Tue., Jan. 12, 2016

Italy in the Year 1000

Europe approached the year 1000 AD with fear and foreboding at the same time that it experienced the most extraordinary leap forward. It feared the chronological marker. For one thousand years, Christians had awaited the Last Judgement, the Revelation, the Final Days. And the approaching year seemed obvious as the possible approaching end of all things. But on the hand, in the secular world, in the world of trade and economic expansion, Europe had not seen times like these since the Fall of Rome. So what was one to think? was everything coming to an end? Or was everything about to get better? The year 1000 is a fascinating moment in European and Italian history. In continental Europe, the Holy Roman Empire established itself as the most powerful state. Otto III made a pilgrimage from Rome to Aachen, stopping at Regensburg, Meissen, Magdeburg, and Gniezno. In Rome, he built the basilica of San Bartolomeo all'Isola, to host the relics of St. Bartholomew. In France, Robert II, the son of Hugh Capet, was the first of the Capetian kings. The Byzantine Empire under the Macedonian dynasty was sorely pressed by the ongoing Muslim conquests, losing many of its eastern territories in the Byzantine–Arab wars (780–1180). At the same time, Byzantium was instrumental in the Christianization of the Ukraine and of other medieval Slavic states. In Great Britain, a unified kingdom of England had developed out of the various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. In Scandinavia, Christianization was in its early stages, with the Althingi of the Icelandic Commonwealth embracing Christianity in the year 1000. On September 9, King Olaf Tryggvason was defeated by an alliance of his enemies in the Battle of Svolder. Sweyn I established Danish control over part of Norway. Oslo, Norway, was founded in 1000. The papacy during this time was in a period of decline, in retrospect known as the saeculum obscurum ("Dark Age") or "pornocracy" ("rule of harlots"), a state of affairs that would result in the Great Schism later in the 11th century. Hungary was established in 1000 as a Christian state. In the next centuries, the Kingdom of Hungary became the pre-eminent cultural power in the Central European region. On December 25, Stephen I was crowned as the first King of Hungary in Esztergom. Sancho III of Navarre became King of Aragon and Navarre. The Reconquista was gaining some ground, but the southern Iberian peninsula would still be dominated by Islam for centuries to come; Córdoba at this time was the world's largest city with 450,000 inhabitants. (The preceding survey based on Wikipedia article on The Year 1000.)

RECOMMENDED READING:

Robert Lacey,

The Year 1000: What Life Was Like at the Turn of the First Millennium,

Back Bay Books (April 1, 2000),

ISBN 9780316511575

RECOMMENDED READING:

Michele Spike,

Tuscan Countess: The Life and Extraordinary Times of Matilda of Canossa ,

Vendome Press; 1st edition (September 28, 2004),

La Contessa Matilda was the most important person in 11th Century Florence. She led the explosive revival of Florence; she endowed and encouraged the church; she rebuilt the architecture. This biography is the first one we have had in English that is really good and worth recommending.

From Publishers Weekly:

The dramatic life of Matilda of Canossa (1046-1115) could easily be the plot of a Pirandello play: there are papal intrigues, warring medieval factions and even an ill-fated marriage to a hunchback that ends in murder. Spike's marvelous biography of the countess takes on all of these events, and also explains how Matilda became an ardent defender of the lands in the Po Valley, which she considered her birthright. Spike deftly conjures the world of pre-Renaissance Italy, where a woman "passed through her life from father to brother, to husband, to son, as each in his turn acted for her welfare." Many of the men in Matilda's life, however, failed to act in her best interests, and under such conditions, the remarkable young woman flouted the traditions of her male-dominated world and managed to defend her small portion of Italy from Henry IV. Using a staggering amount of new research, Spike peels back layer upon layer of previous myth to render a startling new portrait of the countess. (The author also displays a novelist's talent for detail, exploring the unusual alliance between Matilda and Pope Gregory VII, her ally and lover.) Spike's first-person account of her exhaustive research is one of the book's unexpected pleasures; the modern-day characters she encountered during her hunt provide this engrossing historical chronicle with a richly personal subtext. 40 b/w illus.

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Week 12: Tue., Jan. 19, 2016

Italian Art in the Middle Ages: Sculpture

At the right you see Nicola Pisano, Nativiy, Carrara marble, Pisa Baptistry pulpit. Notice Mary and her Roman matron face. Pisano is copying Roman sculpture that is sitting there in Pisa. From 1000 AD to 1300 AD, artists in Europe changed the look of Western art. The change took place with Italian architects, sculptors and painters leading the way. The art of scuplture allows us to follow the transformation without interruption from the Fall of Rome all the way forward to our period, 1000-1300, this Winter Quarter. In Italy alone, there is no permanent interruption in the production of art even in the worst of times. In some periods the production is small, but it still allows us to see the change take place. Italy had one major advantage over other European states: it had the Roman scuptural past sitting all around it. Thus the first hints of Medieval artistic change are visible in cities such as Pisa where the Roman sculptural remains are rich, and local artists such as Nicola Pisano and his son Giovanni Pisano, can lead the way, starting with their own local Roman past. To the right, you see Pisano's Virgin Mary and she will remind you of a Roman matron.

Week 13: Tue., Jan. 26, 2016

Monasteries

In the seventy-plus years between the last Roman Emperor (476 AD) and the death of Benedict (547 AD), Western Europe created a whole new version of Christianity: monastic Christianity. Born in the years of massive social unrest and political collapse, the new monastic life as it came to be lived in Italy under the leadership of Benedict, appealed to both men and women, rich and poor, young and old. It offered people the opportunity to withdraw from the confusion and to move into a safe space and to join a community of like-minded individuals who welcomed the simplicity of monastic life. The single most important individual in the creation of this new way of life was Benedict of Nursia. We met Benedict in Fall Quarter, and now we want to turn to some of the other great monastic houses that became the most important centers of cultural preservation in all of Europe and especially those in Italy. All these houses can be visited today.

- Monte Cassino, founded 529 (Benedict)

- Lerins, France, founded 410.

- Fulda, Germany, founded 744 by disciple of Boniface.

- Cluny, Burgundy, France, founded 910 (Benedictine)

- Camaldoli, Casentino Italy, founded 1012 by Saint Romuald (Benedictine)

- Vallombrosa, Appenine mountains near Florence, founded 1038 by Florentine nobleman.

PART TWO: Visits to some monasteries.

Saint Catherine's Monastery in Sinai, Egypt is one of the oldest monasteries in the world and was begun in 548 AD. It has been in continuous operation since that date and therefore is one of the oldest continuously occupied monasteries in the world. Its official name being Sacred Monastery of the God-Trodden Mount Sinai, lies on the Sinai Peninsula, at the mouth of a gorge at the foot of Mount Sinai, in the city of Saint Catherine in Egypt's South Sinai Governorate.

Week 14: Tue., Feb. 2, 2016

Universities

One of the most important contributions to modern culture that comes from the Middle Ages are the universities. The ancient Greek and Roman world did not have universities. They had institutions of higher learning such as Plato's Academy, but they did not have universities. The name of the institution tells you much about what it proposed to do: universities were supposed to bring all knowledge together in one location with many different professors and students from all over the world, all of whom knew Latin, the language of a Medieval university. Two of the most important of the early universities were Italian: the University of Bologna specializing in Law, and the University of Padova (Padua in English) specializing in Medicine. We will discuss their creation and evolution and the role they played in the growth of Medieval Italy. In both Padova and Bologna, the university is the most important institution in the city and has significant political power and influence. A great university could MAKE a city; it could put it on the map! Thus any threat to withdraw and relocate was a potential catastrophe.

RECOMMENDED READING:

Charles Homer Haskins,

The Rise of the Universities ,

Cornell University Press Paperbacks, 1957 (First edition 1924),

ISBN 9780801490156

"The republication of Charles Homer Haskins' The Rise of Universities is cause for celebration among historians of higher education and among medievalists of all disciplines...Haskins' argument is a powerful one: that today's university system is a direct (and immediate) descendent of the collections of scholars who gathered around master teachers in the great cities of Europe during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries...[His] thesis was profound for its time and remains the guiding interpretation of medieval universities."

—Library Quarterly

PART TWO: Pictures

See below the University of Bologna.

Week 15: Tue., Feb. 9, 2016

The Papacy and the Empire

The two most important institutions of the Middle Ages in Europe were the Holy Catholic Church based in Rome and the Holy Roman Empire based in Germany or some other northern country. These two institutions were seen as extending back into past history to the days of Jesus of Nazareth. Both were seen to be eternal and universal. The truth was something different. The Holy Roman Empire was, as Voltaire remarked: "neither Holy nor Roman nor an Empire." But the mythology saw it as an extension of the real Roman Empire. The idea was that the Roman Empire had not declined and ended but had continued in the form of this newer "Holy Roman Empire" founded by Charlemagne and Pope Leo on Christmas Day in the year 800 AD. The Holy Catholic Church in Rome was on more solid ground. It most definitely was Roman. It was a church, an international church. And one would assume it was Holy. In the Medieval vision, these two institutions were partners in the leadership of the whole Christian world. Pope and Emperor, like Charlemagne and Pope Leo, were to work together to bring about peace and unity in the Christian world. In reality, the two fought most of the time. And the rare moments of complete amity between pope and emperor were brief and historically insignificant. But if the two institutions were competitors more than partners, they were, after all, the two institutions in the Middle Ages that mattered the most. This was especially true for Italy; more so for Italy than all the rest of Europe. One of the two institutions was based in the Italian city of Rome. And the second institution was led by the emperor who spent much of his time in Italy too. So whereas Englishmen might view both institutions as distant and unimportant, citizens of Italy most definitely did not.

RECOMMENDED READING:

James Bryce,

The Holy Roman Empire,

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (September 12, 2012) ,

ISBN 1479208523

The Holy Roman Empire was, according to Voltaire, neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire. But it was long-lived, complex, brutal, important, and fascinating, as is evident from the reading of this notable work published in 1871 by the English jurist, historian and politician, James Bryce (1838 to 1922). Bryce concentrates his considerable erudition on the meaning and significance of the empire’s existence rather than on its chronology. This is an essential work for the understanding of western history.

Reader comments on Amazon:

By Lisa C. Philip on July 8, 2013 Format: Paperback." Even though this book was written over one hundred years ago it is still the best book on the topic. Packed with so much information. Highly recommended for anyone interested in the topic."

The Holy Roman Empire was, according to Voltaire, neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire. But it was long-lived, complex, brutal, important, and fascinating, as is evident from the reading of this notable work published in 1871 by the English jurist, historian and politician, James Bryce (1838 to 1922). Bryce concentrates his considerable erudition on the meaning and significance of the empire’s existence rather than on its chronology. This is an essential work for the understanding of western history.

Reader comments on Amazon:

By Lisa C. Philip on July 8, 2013 Format: Paperback." Even though this book was written over one hundred years ago it is still the best book on the topic. Packed with so much information. Highly recommended for anyone interested in the topic."

Week 16: Tue., Feb. 16, 2016

The Rebirth of the Cities after the Dark Ages

On and around the year 1000 AD the cities of Europe, and especially of Italy, turn a corner. After centuries of war and invasion, almost suddenly, there is peace. Travel on land ad sea is safer. Products move around more easily. People move around more easily. And thus during the Eleventh Century, there is a general resurgence of the European economy and especially that of the cities. The cities grow fast. They expand fast. They build bigger walls. They build huge new cathedrals and huge new city halls like the building on the right, the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. In order to understand this phenomenon we will take one Italian city, Florence, and tell its story from the end of the Roman Empire in the sixth century to the great expansion of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Of all the possible choices for our study, Florence has a major advantage for our study: it was a Roman founded city, it declined as Rome declined, it surged back as all of Europe and Italy rebounded in the eleventh century. Its trajectory reveals exactly the Italian story of so many other cities.

PART TWO: PICTURES

The expansion of Florence in the Middle Ages.

RECOMMENDED READING

This two-volume history of Florence is the best detailed study of Florence ever written. Schevill wrote a masterpiece of well researched narrative history for Florence in 1936 and then it was republished in a Harper Torchbook paperback in 1961. The Harper Torchbook is still out there in used book stores so we have purchased five for our library. But there are still copies left if you want to own one. It is two volumes with the first volume devoted to our period of Medieval History and the second volume on Renaissance Florence. For the Lombards see Medieval Florence (Volume 1) Chapter Three, "Darkness Over Florence."

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU

Week 17: Tue., Feb. 23, 2016

The Normans in Italy

The Norman conquest of southern Italy spanned most of the 11th and 12th centuries, involving many battles and independent conquerors. Only later were these territories in southern Italy united as the Kingdom of Sicily, which included the island of Sicily, the southern third of the Italian Peninsula (except Benevento, which was briefly held twice), the archipelago of Malta and parts of North Africa. Immigrant Norman brigands acclimatised themselves to the Mezzogiorno as mercenaries in the service of Lombard and Byzantine factions, communicating news swiftly back home about opportunities in the Mediterranean. These groups gathered in several places, establishing fiefdoms and states of their own, uniting and elevating their status to de facto independence within fifty years of their arrival. Unlike the Norman conquest of England (1066), which took a few years after one decisive battle, the conquest of southern Italy was the product of decades and a number of battles, few decisive. Many territories were conquered independently, and only later were unified into a single state. Compared to the conquest of England it was unplanned and disorganised, but equally complete. (From Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING:

John Julius Norwich has written an elegant intelligent book on the Normans in Italy. Many of you enjoyed his book on Byzantium in Fall Quarter.

John Julius Norwich,

The Normans in the South, 1016–1130 (The Normans in Sicily),

Faber and Faber (November 9, 2011),

ISBN 0571259642

About the Author: John Julius Norwich was born in 1929. He joined the British Foreign Service after studying French and Russian at Oxford, and left the service in 1964 to become a writer. He has also worked extensively in radio and television, hosting the popular BBC radio panel game My Word! for several years, and writing and presenting historical documentaries. His many books include an acclaimed Byzantium trilogy.

From Amazon, Most Helpful Customer Reviews 6 of 6 people found the following review helpful a lush narrative history about a uniquely dynamic people By Robert J. Crawford on March 10, 2013 Format: Paperback

"This is an excellent popular history of the Normans - the Viking people that occupied NW France, got feudal recognition and were absorbed into the local culture, and then expanded outward with exceptional dynamism. Theirs was an absolutely remarkable rise, from pillagers to nobility and finally, statesmen and relatively enlightened sovereigns. While their takeover of Britain (the last time the island was invaded, let alone conquered) is well known, their career in the South has received relatively little attention. This wonderfully readable book remedies that in a series of stories that are at once scholarly and fun. When the Normans arrived in southern Italy, they were little more than a mercenary force, indeed thieves. They may have been able to boast they were born of French feudal lords, but they were essentially adventurers with nothing. Their brutality was as remarked upon as their thirst for status and glory. At the time of their arrival in 1016, Italy was uneasily divided between the germanic Lombards, Greeks with ties to Byzantium, and the papacy. Sicily was occupied at the time by various sultans, a culturally rich if unstable mix with Greeks and Latins as well. The Normans, and in particular the family of the Hautevilles, came onto the scene and clawed their way to the top. Robert, dubbed the Guiscard, became a major figure, eventually gaining the title of Duke of Apulia from the Pope, who annointed sovereigns all over western christendom. With his brother Roger, with whom he occasionally warred, he brought order to the South and opened an invasion of Sicily. Though constantly at war with unruly lords sworn to him under feudal obligation, Robert was merciful and tolerant once in power, to the surprise of his critics."

Week 18: Tue., Mar. 1, 2016

St Francis of Assisi

Saint Francis of Assisi (Italian: San Francesco d'Assisi; born Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, but nicknamed Francesco ("the Frenchman") by his father; 1181/1182 – October 3, 1226) was an Italian Catholic friar and preacher. He founded the men's Order of Friars Minor, the women’s Order of St. Clare, and the Third Order of Saint Francis for men and women not able to live the lives of itinerant preachers, followed by the early members of the Order of Friars Minor, or the monastic lives of the Poor Clares. Francis is one of the most venerated religious figures in history. Francis' father was Pietro di Bernardone, a prosperous silk merchant. Francis lived the high-spirited life typical of a wealthy young man, even fighting as a soldier for Assisi. While going off to war in 1204, Francis had a vision that directed him back to Assisi, where he lost his taste for his worldly life. On a pilgrimage to Rome, he joined the poor in begging at St. Peter's Basilica. The experience moved him to live in poverty. Francis returned home, began preaching on the streets, and soon gathered followers. His Order was authorized by Pope Innocent III in 1210. He then founded the Order of Poor Clares, which became an enclosed religious order for women, as well as the Order of Brothers and Sisters of Penance (commonly called the Third Order). In 1219, he went to Egypt in an attempt to convert the Sultan to put an end to the conflict of the Crusades. By this point, the Franciscan Order had grown to such an extent that its primitive organizational structure was no longer sufficient. He returned to Italy to organize the Order. Once his community was authorized by the Pope, he withdrew increasingly from external affairs. In 1223, Francis arranged for the first Christmas nativity scene. In 1224, he received the stigmata, making him the first recorded person to bear the wounds of Christ's Passion. He died during the evening hours of October 3, 1226, while listening to a reading he had requested of Psalm 142. On July 16, 1228, he was proclaimed a saint by Pope Gregory IX. He is known as the patron saint of animals and the environment, and is one of the two patron saints of Italy (with Catherine of Siena). It is customary for Catholic and Anglican churches to hold ceremonies blessing animals on his feast day of October 4. He is also known for his love of the Eucharist, his sorrow during the Stations of the Cross, and for the creation of the Christmas crèche or Nativity Scene.. (Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU

Week 19: Tue., Mar. 8, 2016

Italian Art in the Middle Ages: Painting

It was in Italy between 1000 AD and 1300 AD that a small number of painters completely changed the way that the art of painting presented the scene of human activity to the eyes of the viewer. Before that time, the Eastern Christian capital of Constantinople had exerted an overwhelming power over the artistic traditions of Christianity. But with the outbreak of the Iconoclastic Controversy which lasted during the 700's and 800's, and the decision of the Eastern Emperor to ban all representations of divine figures in art, suddenly the international art world changed. Artists who had been active in Constantinople rushed to Italy to continue their careers. And by 1000 AD, Rome was beginning to exercize a new power in Christian art. In the next three hundred years, the Greek style as some called it, was overturned and in its place Italian artists labored to develop a whole new native Italian style, a "Latin" style to replace Greek. The earliest efforts in this iconographic revolution took place in Rome but soon it expanded over all of Italy with Florence becoming the most advanced center of painting by the year 1300. The most important name in this new Florentine artistic leadership is Giotto. You see a detail of his Rucellai Madonna to the right. (The painting is in the Uffizi.) Below is a photograph of the Scrovegni Chapel which was painted by Giotto in 1305 to 1310 with stories of Jesus. It would be fair to say that this chapel contains the most revolutionary artistic heritage anywhere in the European world since the days of Rome.

RECOMMENDED READING

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU

Week 20: Tue., Mar. 15, 2016

The Age of the Cathedrals

By 1300, the economic boom that had begun around 1000 AD was now fully underway and was bearing significant results in the great cities of Italy. Populations were exploding. The city of Florence had to expand its walls three times in a few hundred years. By 1300 Florence contained over 100,000 people. The same was happening in Venice and Milan. Trade was booming. Governments were experimenting with innovative ideas about elections and citizen's rights. The most dramatic evidence of this new culture was to be seen in the various cathedral projects all over Italy. In Milan, Venice, Pisa, Lucca, Siena, and Florence, cities planned massive new cathedral buildings in the center of their city to mark its power and its prestige. The greatest of all these projects was that of Florence. In 1296, the city fathers gathered together to lay the cornerstone of what was to be the largest cathedral in Europe. And the building that emerged did indeed hold that title until Rome decided to build a whole new St Peter's in 1510.

RECOMMENDED READING

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU