Week 21

Week 21: Tuesday, March 29, 2016

"Firenze all 'Apice," Florence at the Summit

In 1300, Giovanni Villani, a Florentine banker attended the great Jubilee of that year proclaimed by Pope Boniface VIII. While in Rome, Villani was struck by the contrast between his own Florence and the legendary ancient capital. Rome seemed to be in decline and his own city seemed to be at her peak. In the 36th chapter of Book 8 of his Chronicle, Villani states that the idea of writing the Cronica was suggested to him during the jubilee of Rome under the following circumstances. After Pope Boniface VIII made in honor of Christ's nativity a great indulgence; Villani writes: "And being on that blessed pilgrimage in the sacred city of Rome and seeing its great and ancient monuments and reading the great deeds of the Romans as described by Virgil, Sallust, Lucan, Livy, Valerius, Orosius, and other masters of history ... I took my prompting from them although I am a disciple unworthy of such an undertaking. But in view of the fact that our city of Florence, daughter and offspring of Rome, was mounting and pursuing great purposes, while Rome was in its decline, I thought it proper to trace in this chronicle the origins of the city of Florence, so far as I have been able to recover them, and to relate the city's further development at greater length, and at the same time to give a brief account of events throughout the world as long as it please God, in the hope of whose favor I undertook the said enterprise rather than in reliance on my own poor wits. And thus in the year 1300, on my return from Rome, I began to compile this book in the name of God and the blessed John the Baptist and in honor of our city of Florence." The Chronicle of Villani is a mark of the optimism and pride of Florentines as they observed the achievements of their city. They were building the largest cathedral in Italy. They were building the largest civic center in Italy. They were completing their new constitution that gave the city the most democratic government in all Italy. Their new Florentine coin called the Florin that was less than fifty years old was now the first choice of every banker and merchant of the whole world. Their painters were chosen for projects all over the world. For Villani. Florence was the best city in the world. And so it seemed in 1300.

RECOMMENDED READING

This two-volume history of Florence is the best detailed study of Florence ever written. Schevill wrote a masterpiece of well researched narrative history for Florence in 1936 and then it was republished in a Harper Torchbook paperback in 1961. The Harper Torchbook is still out there in used book stores so we have purchased five for our library. But there are still copies left if you want to own one. It is two volumes with the first volume devoted to our period of Medieval History and the second volume on Renaissance Florence. For the Lombards see Medieval Florence (Volume 1) Chapter Three, "Darkness Over Florence."

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU

22

Week 22: Tuesday, April 5, 2016

The Papacy in Avignon

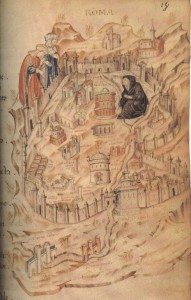

In 1305, Raymond Bertran de Got, Archbishop of Bordeaux, was elected Pope Clement V. De Got was in France at the time of his election, and in the years immediately succeeding his election he tarried on his journey to Rome. The king of France offered him a place to preside if he wished to remain in France. The king of France encouraged him to do this, and under pressure and with blandishments offered by the king, Bishop de Got stopped in Avignon. His successors followed his lead, and so the papacy remained in France for the next 67 years. This state of affairs was a scandal to all of Europe except to France. The king wanted control of the papacy; but the rest of Europe now entered into a dark period for the papacy. Slowly other nations moved on their own independent roads and ideas and theological tracts appeared with more and more radical proposals. In England, John Wycliff suggested no one needed the papacy. The image above is taken from a manuscript in the Biblioteque National in Paris. It shows Rome a black-clad widow mourning her loss. Folio 18 from Bibliotheque Nationale, MS It. 81, Allegorical map of the City of Rome, showing a personification of Rome as a widow during the Avignon Papacy.

23

Week 23: Tuesday, April 12, 2016

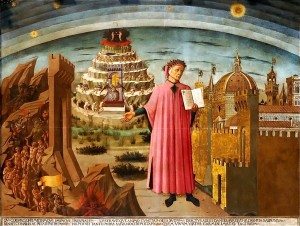

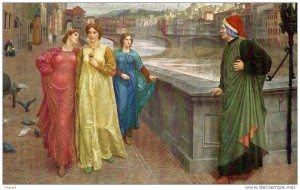

Chrisitianity in Transition: Dante, Beatrice, and the Virgin Mary

In the two centuries between 1100 and 1300, Christianity underwent an almost complete transformation. In the 11th Century, the most prominent representation on the walls of churches was the Last Judgement. People worried, were afraid of the future. Life seemed dangerous and religion warned of catastrophe ahead. Then all of a sudden, something happened. A beautiful and loving mother figure emerged and churches were names for her: Notre Dame. By 1300, a new church anywhere in Europe was dedicated to her. This transformation paralleled the life and work of Dante. It paralleled his own salvation offered to him by his own Lady, his Beatrice.

REQUIRED READING:

Make sure you bring your copy of the Divine Comedy, Inferno, to class as we now discuss and read passages together. We will begin with the first few cantos (songs) and move on. The Mandelbaum translation is the one we have chosen and it is on the Required Texts page for this class. THIS DUAL-LANGUAGE TEXT IS NOT AVAILABLE ON KINDLE BECAUSE THEY CANNOT REPRODUCE THE 2 FACING PAGES WITH ENGLISH AND ITALIAN. WE WANT THE ABILITY TO SEE BOTH ENGLISH AND ITALIAN.

Dante,

The Divine Comedy: Inferno,

translated by Allen Mandelbaum,

Bantam Classic,

ISBN 0553213393

Why choose this translation from among the 100's that exist? Read these comments:

Review "The English Dante of choice."--Hugh Kenner.

"Exactly what we have waited for these years, a Dante with clarity, eloquence, terror, and profoundly moving depths."--Robert Fagles, Princeton University

"Tough and supple, tender and violent . . . vigorous, vernacular . . . Mandelbaum's Dante will stand high among modern translations."--The Christian Science Monitor

"Lovers of the English language will be delighted by this eloquently accomplished enterprise." --Book Review Digest

From the Publisher: This splendid verse translation by Allen Mandelbaum provides an entirely fresh experience of Dante's great poem of penance and hope. As Dante ascends the Mount of Purgatory toward the Earthly Paradise and his beloved Beatrice, through "that second kingdom in which the human soul is cleansed of sin," all the passion and suffering, poetry and philosophy are rendered with the immediacy of a poet of our own age. With extensive notes and commentary prepared especially for this edition.

RECOMMENDED READING:

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED: There is a good biography of Dante written by the late R. W. B. Lewis, Dante (ISBN 0670899097) and it is excellent and exactly what many of you will want: a short (200 pages), well-written, inexpensive ($19.95) biography of Dante. It is perfect for our course and although I don't want to make it a required book, I am sure that anyone who buys it will be happy they did.

PART TWO: Dante in Florence.

24

Week 24: Tuesday, April 19, 2016

Christianity in Transition: Dante and Beatrice in Purgatory

The idea of Purgatory was a relatively new idea when Dante wrote his own Part Two of his Commedia. The idea had first appeared in Paris in the late 12th Century and had been elaborated and adopted in Rome by a Church Council in 1279. Now Dante wrote his own picture of Purgatory and solidified its image and meaning for all readers of his poem. By 1330, due to the unprecedented success of the Commedia, Purgatory had become an accepted vision of the afterlife and Dante's three-part epic continued to make it popular with readers and worshipers all over Europe. The great climactic scene of Dante's journey through Purgatory is his meeting with Beatrice in Cantos 28, 29, 30.

REQUIRED READING:

Make sure you bring your copy of the Divine Comedy, to class so that we can discuss and read passages together. In the Purgatorio, we are particularly interested in Cantos 28, 29, and 30 where DANTE MEETS BEATRICE!: THIS DUAL-LANGUAGE TEXT IS NOT AVAILABLE ON KINDLE BECAUSE THEY CANNOT REPRODUCE THE 2 FACING PAGES WITH ENGLISH AND ITALIAN. WE WANT THE ABILITY TO SEE BOTH ENGLISH AND ITALIAN.

RECOMMENDED READING

This study of the origins of the idea of Purgatory is one of the greatest works of intellectual and social history ever written. jacques Le Goff was Professor of History in Paris at the Sorbonne and he was the master of medieval history. This work is breathtaking in its originality and in its clarity. Le Goff was a master and we mourn his passing just this past year, 2014. This book was originally published in French in 1984 in Paris and is here translated by Arthur Goldhammer for University of Chicago Press.

This study of the origins of the idea of Purgatory is one of the greatest works of intellectual and social history ever written. jacques Le Goff was Professor of History in Paris at the Sorbonne and he was the master of medieval history. This work is breathtaking in its originality and in its clarity. Le Goff was a master and we mourn his passing just this past year, 2014. This book was originally published in French in 1984 in Paris and is here translated by Arthur Goldhammer for University of Chicago Press.

Jacques Le Goff,

The Birth of Purgatory,

University of Chicago Press,

ISBN 0226470830

About the author: Jacques Le Goff (1 January 1924 – 1 April 2014) was a French historian and prolific author specializing in the Middle Ages, particularly the 12th and 13th centuries. Le Goff championed the Annales School movement, which emphasizes long-term trends over the topics of politics, diplomacy, and war that dominated 19th century historical research. From 1972 to 1977, he was the head of the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS). He was a leading figure of New History, related to cultural history. Le Goff argued that the Middle Ages formed a civilization of its own, distinct from both the Greco-Roman antiquity and the modern world. A prolific medievalist of international renown, Le Goff was sometimes considered the principal heir and continuator of the movement known as Annales School (École des Annales), founded by his intellectual mentor Marc Bloch. Le Goff succeeded Fernand Braudel in 1972 at the head of the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS) and was succeeded by François Furet in 1977. Along with Pierre Nora, he was one of the leading figures of New History (Nouvelle histoire) in the 1970s. In his 1984 book The Birth of Purgatory, he argued that the conception of purgatory as a physical place, rather than merely as a state, dates to the 12th century, the heyday of medieval otherworld-journey narratives such as the Irish Visio Tnugdali, and of pilgrims' tales about St Patrick's Purgatory, a cavelike entrance to purgatory on a remote island in Ireland. Other books by Le Goff: Time, Work, & Culture in the Middle Ages, translated by Arthur Goldhammer.

(Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 1980) Constructing the Past: Essays in Historical Methodology, edited by Jacques Le Goff and Pierre Nora.

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985) The Medieval Imagination, translated by Arthur Goldhammer.

(Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 1988) Your Money or Your Life: Economy and Religion in the Middle Ages, translated by Patricia Ranum.

(New York : Zone Books, 1988) Medieval Civilization, 400-1500, translated by Julia Barrow.

(Oxford: Blackwell, 1988) The Medieval World, edited by Jacques Le Goff, translated by Lydia G. Cochrane.

(London: Parkgate, 1990) The Birth of Purgatory, translated by Arthur Goldhammer.

(Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1990) History and Memory, translated by Steven Rendall and Elizabeth Claman.

(New York: Columbia University Press, 1992) Intellectuals in the Middle Ages, translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan.

(Oxford: Blackwell, 1993) Saint Louis (Paris: Gallimard, 1996) Saint Francis of Assisi, trans. Christine Rhone

(London: Routledge, 2003) The Birth of Europe, translated by Janet Lloyd.

(Oxford: Blackwell, 2005) In Search of Sacred Time, translated by Lydia G. Cochrane

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014)

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED: There is a good biography of Dante written by the late R. W. B. Lewis, Dante (ISBN 0670899097) and it is excellent and exactly what many of you will want: a short (200 pages), well-written, inexpensive ($19.95) biography of Dante. It is perfect for our course and although I don't want to make it a required book, I am sure that anyone who buys it will be happy they did.

PART TWO: Dante in Verona where he wrote the Purgatory

25

Week 25: Monday, April 27, 2015

Italy on the Edge; 1348

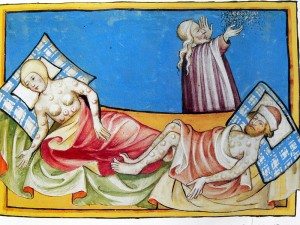

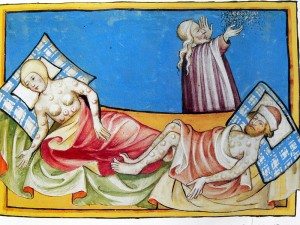

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 75 to 200 million people and peaking in Europe in the years 1346–53. Although there were several competing theories as to the etiology of the Black Death, analysis of DNA from victims in northern and southern Europe published in 2010 and 2011 indicates that the pathogen responsible was the Yersinia pestis bacterium, probably causing several forms of plague.

The Black Death is thought to have originated in the arid plains of Central Asia, where it then travelled along the Silk Road, reaching the Crimea by 1343.] From there, it was most likely carried by Oriental rat fleas living on the black rats that were regular passengers on merchant ships. Spreading throughout the Mediterranean and Europe, the Black Death is estimated to have killed 30–60% of Europe's total population. In total, the plague reduced the world population from an estimated 450 million down to 350–375 million in the 14th century. The aftermath of the plague created a series of religious, social, and economic upheavals, which had profound effects on the course of European history. It took 150 years for Europe's population to recover.[citation needed] The plague recurred occasionally in Europe until the 19th century. (Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING

The best recent study of the Black Death is this excellent book of 2005 by John Kelly.

John Kelly,

The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death,

Harper Pennial paperback, 2005,

ISBN 0060006935

REVIEW:

Amazon.com Review. A book chronicling one of the worst human disasters in recorded history really has no business being entertaining. But John Kelly's The Great Mortality is a page-turner despite its grim subject matter and graphic detail. Credit Kelly's animated prose and uncanny ability to drop his reader smack in the middle of the 14th century, as a heretofore unknown menace stalks Eurasia from "from the China Sea to the sleepy fishing villages of coastal Portugal [producing] suffering and death on a scale that, even after two world wars and twenty-seven million AIDS deaths worldwide, remains astonishing." Take Kelly's vivid description of London in the fall of 1348: "A nighttime walk across Medieval London would probably take only twenty minutes or so, but traversing the daytime city was a different matter.... Imagine a shopping mall where everyone shouts, no one washes, front teeth are uncommon and the shopping music is provided by the slaughterhouse up the road." Yikes, and that's before just about everything with a pulse starts dying and piling up in the streets, reducing the population of Europe by anywhere from a third to 60 percent in a few short years. In addition to taking readers on a walking tour through plague-ravaged Europe, Kelly heaps on the ancillary information and every last bit of it is captivating. We get a thorough breakdown of the three types of plagues that prey on humans; a detailed account of how the plague traveled from nation to nation (initially by boat via flea-infested rats); how floods (and the appalling hygiene of medieval people) made Europe so susceptible to the disease; how the plague triggered a new social hierarchy favoring women and the proletariat but also sparked vicious anti-Semitism; and especially, how the plague forever changed the way people viewed the church. Engrossing, accessible, and brimming with first-hand accounts drawn from the Middle Ages, The Great Mortality illuminates and inspires. History just doesn't get better than that. --Kim Hughes

RECOMMENDED READING

If you would like to read an account of human beings and disease then this small brilliant book from by the greatest living American historian, William McNeill will serve you well. I say the "greatest living..." and of course that is debatable, but for me, I value what William McNeill has done as the highest achievement in history, especially his masterpiece,The Rise of the West. It is still the best one-volume history of Western Civilization. Plagues and Peoples is a very wide rich book. It begins with a short introduction to the anthropological history of humankind and always with an eye to how disease has played its part. The section of the book that will most interest us this week is Chapter Four: The Impact of the Mongol Empire on Shifting Disease Balances, 1200–1500. This chapter is the best analysis of how the Black Death was connected to larger issues of populations and politics. It is worth owning the book if only to go directly to Chapter 4.

William H. McNeill,

Plagues and Peoples,

Doubleday Anchor paperback, first published in 1976. 2005,

ISBN 0385121229

Amazon.com Review

No small themes for historian William McNeill: he is a writer of big, sweeping books, from The Rise of the West to The History of the World. Plagues and Peoples considers the influence of infectious diseases on the course of history, and McNeill pays special attention to the Black Death of the 13th and 14th centuries, which killed millions across Europe and Asia. (At one point, writes McNeill, 10,000 people in Constantinople alone were dying each day from the plague.) With the new crop of plagues and epidemics in our own time, McNeill's quiet assertion that "in any effort to understand what lies ahead the role of infectious disease cannot properly be left out of consideration" takes on new significance.

From the Publisher

McNeill's highly acclaimed work is a brilliant and challenging account of the effects of disease on human history. His sophisticated analysis and detailed grasp of the subject make this book fascinating reading. By the author of The Rise Of The West. Upon its original publication, Plagues and Peoples was an immediate critical and popular success, offering a radically new interpretation of world history as seen through the extraordinary impact--political, demographic, ecological, and psychological--of disease on cultures. From the conquest of Mexico by smallpox as much as by the Spanish, to the bubonic plague in China, to the typhoid epidemic in Europe, the history of disease is the history of humankind. With the identification of AIDS in the early 1980s, another chapter has been added to this chronicle of events, which William McNeill explores in his new introduction to this updated editon. Thought-provoking, well-researched, and compulsively readable, Plagues and Peoples is that rare book that is as fascinating as it is scholarly, as intriguing as it is enlightening. "A brilliantly conceptualized and challenging achievement" (Kirkus Reviews), it is essential reading, offering a new perspective on human history.

26

Week 26: Tuesday, May 3, 2016

Boccaccio, the Decameron, and the Plague

Giovanni Boccaccio was born in 1313, in the small town of Certaldo which is located just south of Florence in the Val d' Elsa. His father was a merchant-banker and in 1326 the family loved to Naples. IN this huge bustling international city, young Giovanni went to work in his father's bank to learn banking. But he soon realized he cared nothing about business so convinced his father to allow him to enter the University of Naples to study Law. Giovanni cared only a little more about the Law than he did about banking, but he loved the university and used his six years there to acquire a brilliant education. Naples was much more international than Florence with ties to the Islamic work, to Egypt, to Greece, and the Byzantine empire. And so when Giovanni returned to Florence in 1341, he now possessed a sophisticated education that included knowledge of some Greek, and a knowledge of philosophy, law, and literature. During the next six years, Boccaccio wrote a number of works and attempted to create a career in literature. A professional writer at that time relied on patrons. There was no copyright, no income from one's printed works. So the professional writer looked for financial support from various sponsors: political, religious, private. Then the event that would change his life and his career and his fame hit all of Italy: The Black Plague. Florence was hit as hard as any large city. And in months, the population of this city of 100,000 fell by half. Maybe more. Boccaccio saw it all up close, because his father was serving his beloved city as Minister of Supply, with all the responsibilities of trying to help the desperate population. He died the next year worn out by his work for his city. Boccaccio launched the book that would make him famous in 1349, as his family tried to recover from the Pest and from the death of the Patriarch of the family. Boccaccio sat down in 1349 and began to write The Decameron. The success of the book was phenominal. It made its author famous overnight. It is still one of the most popular books ever written in Italian.

RECOMMENDED READING:

This is an excellent edition of selected stories from the Decameron as well as important critical articles from experts on Boccaccio and the most important early biography of him.

Giovanni Boccaccio,

The Decameron (Selections),

translated by Peter Bondanella,

Norton Critical Edition,

ISBN 0393091325

AMAZON REVIEW:

'The Decameron' is a series of 100 stories, ten stories told each night by ten different people who had left the city for a country sojourn to escape a time of plague. Giovanni Boccaccio, an Italian author known as part of the founding trinity of Italian literature (the others are Dante and Petrarca), was born in 1313, and produced most of his literary works by his mid-30s. The ten characters in 'The Decameron' were all young people, much like Boccaccio, and the passions, interests and issues of his own age is illustrated among these folk -- Boccaccio's possibly-fictitious love, Fiammetta, is similarly one of the characters here. This edition by Norton does not include all 100 stories, but rather 21 selected stories, many of the more popular ones, selected by professors Mark Musa and Peter Bondanella (professors at my university when I was there 20 years ago), who are also known for their editing and translation of works by Dante and Machiavelli. There are selections from each 'day' (set of 10 stories), as well as a few of the extra texts, such as a prologue, introduction, and overall conclusion by Boccaccio. These are edited to fit together, as Boccaccio's tales often would wind from one story to the next, making a selection of disconnected stories difficult in transition without editing. There are also two different kinds of critical analytical materials included in this Norton Critical Edition. The first includes personal correspondence samples, particularly between Boccaccio and Petrarca; these date even after the writing of 'The Decameron', showing the interest and reactions. These materials include other contemporary and closely-following generations' reactions and influences from 'The Decameron'.

RECOMMENDED READING

John Kelly,

The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death,

Harper Pennial paperback, 2005,

ISBN 0060006935

REVIEW:

Amazon.com Review. A book chronicling one of the worst human disasters in recorded history really has no business being entertaining. But John Kelly's The Great Mortality is a page-turner despite its grim subject matter and graphic detail. Credit Kelly's animated prose and uncanny ability to drop his reader smack in the middle of the 14th century, as a heretofore unknown menace stalks Eurasia from "from the China Sea to the sleepy fishing villages of coastal Portugal [producing] suffering and death on a scale that, even after two world wars and twenty-seven million AIDS deaths worldwide, remains astonishing." Take Kelly's vivid description of London in the fall of 1348: "A nighttime walk across Medieval London would probably take only twenty minutes or so, but traversing the daytime city was a different matter.... Imagine a shopping mall where everyone shouts, no one washes, front teeth are uncommon and the shopping music is provided by the slaughterhouse up the road." Yikes, and that's before just about everything with a pulse starts dying and piling up in the streets, reducing the population of Europe by anywhere from a third to 60 percent in a few short years. In addition to taking readers on a walking tour through plague-ravaged Europe, Kelly heaps on the ancillary information and every last bit of it is captivating. We get a thorough breakdown of the three types of plagues that prey on humans; a detailed account of how the plague traveled from nation to nation (initially by boat via flea-infested rats); how floods (and the appalling hygiene of medieval people) made Europe so susceptible to the disease; how the plague triggered a new social hierarchy favoring women and the proletariat but also sparked vicious anti-Semitism; and especially, how the plague forever changed the way people viewed the church. Engrossing, accessible, and brimming with first-hand accounts drawn from the Middle Ages, The Great Mortality illuminates and inspires. History just doesn't get better than that. --Kim Hughes

This two-volume history of Florence is the best detailed study of Florence ever written. Schevill wrote a masterpiece of well researched narrative history for Florence in 1936 and then it was republished in a Harper Torchbook paperback in 1961. The Harper Torchbook is still out there in used book stores so we have purchased five for our library. But there are still copies left if you want to own one. It is two volumes with the first volume devoted to our period of Medieval History and the second volume on Renaissance Florence. For the Lombards see Medieval Florence (Volume 1) Chapter Three, "Darkness Over Florence."

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU

27

Week 27: Tuesday, May 10, 2016

Painting in Italy After the Black Death

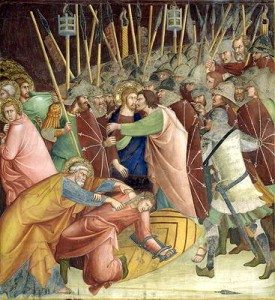

During the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Italian painters pursued a common goal. Each new generation explored ways to portray the human being in a more and more true to life style. each generation explored ways to portray the physical space in which the human being dwells in a more and more realistic way. Rooms became deeper, floors and ceilings helped define interior space, space developed a more three-dimensional appearance. Each new generation explored the creation of this rich new world in which human bodies were solid and sometimes beautiful, and rooms and houses and spaces took on a solid deep reality. The result was such that by 1340 in the work of Giotto and his followers, Italian painters had created a style of painting like nothing that ever been seen before: not in Greece, not in Rome. Human beings had grace and substance and stood solid on the ground. The countryside unwound in beautiful colorful vistas. A kind of soft calm settled over the streets and houses of Italy in 1340. Then disaster struck. Just at the moment that Giotto and his colleagues were creating this rich new world, the Black Plague struck. And nothing was the same after. Millard Meiss noticed all this and in a groundbreaking book, he pointed to the drastic change in the painting of Florence and Siena after the Black Death and that will be our subject tonight.

RECOMMENDED READING

The book noted below is the basis for our lecture tonight. The author of the book, Millard Meiss, a Princeton university art historian, wrote one of the great books of all time in the field of art history when he explored the relationship between the Black Death and painting. It was a brilliant idea and he found evidence to support his theory that the Black Death had changed the whole society and that one change was evident in the painting done in the years immmediately succeeding the Black Death. Used copies are available at Amazon.

About Millard Meiss: Millard Meiss (March 25, 1904 - June 12, 1975) was an American art historian, one of whose specialties was Gothic architecture. A professor at Princeton University, among his many important contributions are Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death and French Painting in the Time of Jean de Berry. He organized the first meeting in the United States of the Congress of the International Committee of the History of Art, and was elected the organization's president. In 1966, he assisted in Florence with restoration efforts following the 1966 Flood of the Arno River, despite being in ill health.

Unfortunately for us, this is such a popular book even many yeara after its initial publication that the price for a new paperback is high. But there are many used copies at good prices. If you pay $10.00 you get a copy described as very good.

Millard Meiss,

Painting in Florence and Siena After the Black Death,

Princeton University Press, 1979,

ISBN 0691003122

John Kelly,

The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death,

Harper Pennial paperback, 2005,

ISBN 0060006935

REVIEW:

Amazon.com Review. A book chronicling one of the worst human disasters in recorded history really has no business being entertaining. But John Kelly's The Great Mortality is a page-turner despite its grim subject matter and graphic detail. Credit Kelly's animated prose and uncanny ability to drop his reader smack in the middle of the 14th century, as a heretofore unknown menace stalks Eurasia from "from the China Sea to the sleepy fishing villages of coastal Portugal [producing] suffering and death on a scale that, even after two world wars and twenty-seven million AIDS deaths worldwide, remains astonishing." Take Kelly's vivid description of London in the fall of 1348: "A nighttime walk across Medieval London would probably take only twenty minutes or so, but traversing the daytime city was a different matter.... Imagine a shopping mall where everyone shouts, no one washes, front teeth are uncommon and the shopping music is provided by the slaughterhouse up the road." Yikes, and that's before just about everything with a pulse starts dying and piling up in the streets, reducing the population of Europe by anywhere from a third to 60 percent in a few short years. In addition to taking readers on a walking tour through plague-ravaged Europe, Kelly heaps on the ancillary information and every last bit of it is captivating. We get a thorough breakdown of the three types of plagues that prey on humans; a detailed account of how the plague traveled from nation to nation (initially by boat via flea-infested rats); how floods (and the appalling hygiene of medieval people) made Europe so susceptible to the disease; how the plague triggered a new social hierarchy favoring women and the proletariat but also sparked vicious anti-Semitism; and especially, how the plague forever changed the way people viewed the church. Engrossing, accessible, and brimming with first-hand accounts drawn from the Middle Ages, The Great Mortality illuminates and inspires. History just doesn't get better than that. --Kim Hughes

28

Week 28: Tuesday, May 17, 2016

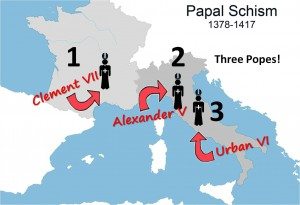

Too Many Popes

In Week 22, we studied the Papacy in Avignon. The popes stayed in Avignon from 1305 to 1382. By 1382, many in the church were aware that the continued French residency of the popes was damaging the international Christian church and so they began to organize to try to bring back the popes to Rome. Petrarch was one influential leader in this movement. He went to Avignon and begged the pope to bring the papacy back to Rome. Finally, on September 13, 1376, Gregory XI abandoned Avignon and moved his court to Rome (arriving on January 17, 1377), officially ending the Avignon Papacy. On April 16, 1378, a College of Cardinals in Rome chose an Italian, Bartolomeo Prignano, as Pope Urban VI. Urban turned out to be a terrible diplomat and a bullheaded leader who angered all the Frenchmen. One night they slipped out of Rome and traveled back to France where they elected a new French Pope: In 1382, an international effort led to the election of an Italian, Benedetto.....to the Papal Throne, and he promised to restore both the city and the institution to its former glory. But he alienated everyone and the French cardinals escaped Rome into he night, and elected one of their own as a new pope, Pope Clement VII, and now there were two popes. The Papal Schism of Europe. And it was going to get worse. The Papal Schism of the fourteenth century did terrible damage to the Papacy in the eyes of the faithful. The one greatest virtue that the Papal leader had always possessed was that he was the one true apostolic successor to Jesus. For 1300 years, pope after pope had been elected without interruption, to sit on the seat of St Peter. But with the outbreak of Schism, that claim was now laid bare. And everyone began to wonder whether the Papacy itself was flawed and worthless. Some suggested that maybe we did not need a Pope!

RECOMMENDED READING

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU

29

Week 29: Tuesday, May 24, 2016

Islam and Christianity in the 14th Century

During week 29 we want to look at the changing relationship of Islam and Christianity in the Mediterranean and especially in Italy. The 600 years between the Islamic invasion of Spain and the last Crusade witnessed a change in fortunes for the two sides of the confrontation between Muslims and Christians.

In 711, Cristendom was disorganized, attacked from all sides by various invading peoples, and lacking any central authority. By 1300, Italy was rich and successful. The enemy across the seas was less frightening than in the days when Islamic ships sailed right up the Tiber river to the Vatican. As Europe gained confidence, it also gained intellectual confidence. This new confidence allowed European professors, philosophers, doctors, and and artists to examine with a more open attitude the knowledge held in the Islamic societies.

RECOMMENDED READING

This is the best one-volume introduction to Islam.

Bernard Ellis Lewis,

Islam: The Religion and the People,

Pearson Prentice Hall; 1 edition (August 29, 2008),

ISBN 0132230852

Praise for Bernard Lewis:

"For newcomers to the subject, Bernard Lewis is the man." TIME Magazine

“The doyen of Middle Eastern studies." The New York Times

“No one writes about Muslim history with greater authority, or intelligence, or literary charm.” British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper.

This is the best one-volume study of Christian-Islam relations in the Middle Ages and it is especially excellent on Spain. Disregard the bizarre user reviews on Amazon. Most of them seem to be motivated by contemporary politcal issues rather than Wheatcroft's excellent history.

Andrew Wheatcroft,

Infidels: A History of the Conflict Between Christendom and Islam,

Random House paperback, 2003,

ISBN 0812972392

From Booklist

*Starred Review* In the roar of skyscrapers collapsing in New York and in the thunder of fusillades in Afghanistan and Iraq, a leading British historian hears echoes of battles fought centuries ago. This timely chronicle amplifies those echoes to show how much ancient animosities pervade the modern conflict between radical Islamic terrorist Osama bin Laden and America. Impelling the Muslim and Christian combatants who crossed swords at Jerusalem and Granada, at Lepanto, Constantinople, and Missolonghi, these ancient hatreds inspired daring innovations in military weaponry and tactics, as well as astonishing enlargements in both faiths' religious demonology. Wheatcroft recounts the clashes of arms--jihad and crusade--in narrative taut and memorable. With rare sophistication, he also traces the perplexing ways religious orthodoxy now reinforced, now checked the political and economic impulses shaping Europe and the Levant. But readers will praise Wheatcroft most for his acute psychological analysis of how Muslim and Christian leaders alike imbued their followers with hostility toward those who adhered to alien creeds. It is this analysis that lends force to the concluding commentary on how President Bush has unwittingly tapped into a very old reservoir of religious enmity with his absolutist rhetoric calling for a "crusade" against the terrorist evil. As a work that interprets today's headlines within a very long chronology, this book will attract a large audience. Bryce Christensen Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved.

30

Week 30: Tuesday, May 31, 2016

Retrospective on the Art of the Middle Ages

In our last class meeting of our study of Medieval Italy, we will look back on the whole story of art from the Fall of Rome to the dawn of the Renaissance in 1400. We will look back at all three arts: painting, sculpture, and architecture, and we will see how Italy changed the look of Western Art in this one thousand years.

All

Week 21: Tue., Mar. 29, 2016

"Firenze all 'Apice," Florence at the Summit

In 1300, Giovanni Villani, a Florentine banker attended the great Jubilee of that year proclaimed by Pope Boniface VIII. While in Rome, Villani was struck by the contrast between his own Florence and the legendary ancient capital. Rome seemed to be in decline and his own city seemed to be at her peak. In the 36th chapter of Book 8 of his Chronicle, Villani states that the idea of writing the Cronica was suggested to him during the jubilee of Rome under the following circumstances. After Pope Boniface VIII made in honor of Christ's nativity a great indulgence; Villani writes: "And being on that blessed pilgrimage in the sacred city of Rome and seeing its great and ancient monuments and reading the great deeds of the Romans as described by Virgil, Sallust, Lucan, Livy, Valerius, Orosius, and other masters of history ... I took my prompting from them although I am a disciple unworthy of such an undertaking. But in view of the fact that our city of Florence, daughter and offspring of Rome, was mounting and pursuing great purposes, while Rome was in its decline, I thought it proper to trace in this chronicle the origins of the city of Florence, so far as I have been able to recover them, and to relate the city's further development at greater length, and at the same time to give a brief account of events throughout the world as long as it please God, in the hope of whose favor I undertook the said enterprise rather than in reliance on my own poor wits. And thus in the year 1300, on my return from Rome, I began to compile this book in the name of God and the blessed John the Baptist and in honor of our city of Florence." The Chronicle of Villani is a mark of the optimism and pride of Florentines as they observed the achievements of their city. They were building the largest cathedral in Italy. They were building the largest civic center in Italy. They were completing their new constitution that gave the city the most democratic government in all Italy. Their new Florentine coin called the Florin that was less than fifty years old was now the first choice of every banker and merchant of the whole world. Their painters were chosen for projects all over the world. For Villani. Florence was the best city in the world. And so it seemed in 1300.

RECOMMENDED READING

This two-volume history of Florence is the best detailed study of Florence ever written. Schevill wrote a masterpiece of well researched narrative history for Florence in 1936 and then it was republished in a Harper Torchbook paperback in 1961. The Harper Torchbook is still out there in used book stores so we have purchased five for our library. But there are still copies left if you want to own one. It is two volumes with the first volume devoted to our period of Medieval History and the second volume on Renaissance Florence. For the Lombards see Medieval Florence (Volume 1) Chapter Three, "Darkness Over Florence."

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU

Week 22: Tue., Apr. 5, 2016

The Papacy in Avignon

In 1305, Raymond Bertran de Got, Archbishop of Bordeaux, was elected Pope Clement V. De Got was in France at the time of his election, and in the years immediately succeeding his election he tarried on his journey to Rome. The king of France offered him a place to preside if he wished to remain in France. The king of France encouraged him to do this, and under pressure and with blandishments offered by the king, Bishop de Got stopped in Avignon. His successors followed his lead, and so the papacy remained in France for the next 67 years. This state of affairs was a scandal to all of Europe except to France. The king wanted control of the papacy; but the rest of Europe now entered into a dark period for the papacy. Slowly other nations moved on their own independent roads and ideas and theological tracts appeared with more and more radical proposals. In England, John Wycliff suggested no one needed the papacy. The image above is taken from a manuscript in the Biblioteque National in Paris. It shows Rome a black-clad widow mourning her loss. Folio 18 from Bibliotheque Nationale, MS It. 81, Allegorical map of the City of Rome, showing a personification of Rome as a widow during the Avignon Papacy.

Week 23: Tue., Apr. 12, 2016

Chrisitianity in Transition: Dante, Beatrice, and the Virgin Mary

In the two centuries between 1100 and 1300, Christianity underwent an almost complete transformation. In the 11th Century, the most prominent representation on the walls of churches was the Last Judgement. People worried, were afraid of the future. Life seemed dangerous and religion warned of catastrophe ahead. Then all of a sudden, something happened. A beautiful and loving mother figure emerged and churches were names for her: Notre Dame. By 1300, a new church anywhere in Europe was dedicated to her. This transformation paralleled the life and work of Dante. It paralleled his own salvation offered to him by his own Lady, his Beatrice.

REQUIRED READING:

Make sure you bring your copy of the Divine Comedy, Inferno, to class as we now discuss and read passages together. We will begin with the first few cantos (songs) and move on. The Mandelbaum translation is the one we have chosen and it is on the Required Texts page for this class. THIS DUAL-LANGUAGE TEXT IS NOT AVAILABLE ON KINDLE BECAUSE THEY CANNOT REPRODUCE THE 2 FACING PAGES WITH ENGLISH AND ITALIAN. WE WANT THE ABILITY TO SEE BOTH ENGLISH AND ITALIAN.

Dante,

The Divine Comedy: Inferno,

translated by Allen Mandelbaum,

Bantam Classic,

ISBN 0553213393

Why choose this translation from among the 100's that exist? Read these comments:

Review "The English Dante of choice."--Hugh Kenner.

"Exactly what we have waited for these years, a Dante with clarity, eloquence, terror, and profoundly moving depths."--Robert Fagles, Princeton University

"Tough and supple, tender and violent . . . vigorous, vernacular . . . Mandelbaum's Dante will stand high among modern translations."--The Christian Science Monitor

"Lovers of the English language will be delighted by this eloquently accomplished enterprise." --Book Review Digest

From the Publisher: This splendid verse translation by Allen Mandelbaum provides an entirely fresh experience of Dante's great poem of penance and hope. As Dante ascends the Mount of Purgatory toward the Earthly Paradise and his beloved Beatrice, through "that second kingdom in which the human soul is cleansed of sin," all the passion and suffering, poetry and philosophy are rendered with the immediacy of a poet of our own age. With extensive notes and commentary prepared especially for this edition.

RECOMMENDED READING:

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED: There is a good biography of Dante written by the late R. W. B. Lewis, Dante (ISBN 0670899097) and it is excellent and exactly what many of you will want: a short (200 pages), well-written, inexpensive ($19.95) biography of Dante. It is perfect for our course and although I don't want to make it a required book, I am sure that anyone who buys it will be happy they did.

PART TWO: Dante in Florence.

Week 24: Tue., Apr. 19, 2016

Christianity in Transition: Dante and Beatrice in Purgatory

The idea of Purgatory was a relatively new idea when Dante wrote his own Part Two of his Commedia. The idea had first appeared in Paris in the late 12th Century and had been elaborated and adopted in Rome by a Church Council in 1279. Now Dante wrote his own picture of Purgatory and solidified its image and meaning for all readers of his poem. By 1330, due to the unprecedented success of the Commedia, Purgatory had become an accepted vision of the afterlife and Dante's three-part epic continued to make it popular with readers and worshipers all over Europe. The great climactic scene of Dante's journey through Purgatory is his meeting with Beatrice in Cantos 28, 29, 30.

REQUIRED READING:

Make sure you bring your copy of the Divine Comedy, to class so that we can discuss and read passages together. In the Purgatorio, we are particularly interested in Cantos 28, 29, and 30 where DANTE MEETS BEATRICE!: THIS DUAL-LANGUAGE TEXT IS NOT AVAILABLE ON KINDLE BECAUSE THEY CANNOT REPRODUCE THE 2 FACING PAGES WITH ENGLISH AND ITALIAN. WE WANT THE ABILITY TO SEE BOTH ENGLISH AND ITALIAN.

RECOMMENDED READING

This study of the origins of the idea of Purgatory is one of the greatest works of intellectual and social history ever written. jacques Le Goff was Professor of History in Paris at the Sorbonne and he was the master of medieval history. This work is breathtaking in its originality and in its clarity. Le Goff was a master and we mourn his passing just this past year, 2014. This book was originally published in French in 1984 in Paris and is here translated by Arthur Goldhammer for University of Chicago Press.

This study of the origins of the idea of Purgatory is one of the greatest works of intellectual and social history ever written. jacques Le Goff was Professor of History in Paris at the Sorbonne and he was the master of medieval history. This work is breathtaking in its originality and in its clarity. Le Goff was a master and we mourn his passing just this past year, 2014. This book was originally published in French in 1984 in Paris and is here translated by Arthur Goldhammer for University of Chicago Press.

Jacques Le Goff,

The Birth of Purgatory,

University of Chicago Press,

ISBN 0226470830

About the author: Jacques Le Goff (1 January 1924 – 1 April 2014) was a French historian and prolific author specializing in the Middle Ages, particularly the 12th and 13th centuries. Le Goff championed the Annales School movement, which emphasizes long-term trends over the topics of politics, diplomacy, and war that dominated 19th century historical research. From 1972 to 1977, he was the head of the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS). He was a leading figure of New History, related to cultural history. Le Goff argued that the Middle Ages formed a civilization of its own, distinct from both the Greco-Roman antiquity and the modern world. A prolific medievalist of international renown, Le Goff was sometimes considered the principal heir and continuator of the movement known as Annales School (École des Annales), founded by his intellectual mentor Marc Bloch. Le Goff succeeded Fernand Braudel in 1972 at the head of the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS) and was succeeded by François Furet in 1977. Along with Pierre Nora, he was one of the leading figures of New History (Nouvelle histoire) in the 1970s. In his 1984 book The Birth of Purgatory, he argued that the conception of purgatory as a physical place, rather than merely as a state, dates to the 12th century, the heyday of medieval otherworld-journey narratives such as the Irish Visio Tnugdali, and of pilgrims' tales about St Patrick's Purgatory, a cavelike entrance to purgatory on a remote island in Ireland. Other books by Le Goff: Time, Work, & Culture in the Middle Ages, translated by Arthur Goldhammer.

(Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 1980) Constructing the Past: Essays in Historical Methodology, edited by Jacques Le Goff and Pierre Nora.

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985) The Medieval Imagination, translated by Arthur Goldhammer.

(Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 1988) Your Money or Your Life: Economy and Religion in the Middle Ages, translated by Patricia Ranum.

(New York : Zone Books, 1988) Medieval Civilization, 400-1500, translated by Julia Barrow.

(Oxford: Blackwell, 1988) The Medieval World, edited by Jacques Le Goff, translated by Lydia G. Cochrane.

(London: Parkgate, 1990) The Birth of Purgatory, translated by Arthur Goldhammer.

(Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1990) History and Memory, translated by Steven Rendall and Elizabeth Claman.

(New York: Columbia University Press, 1992) Intellectuals in the Middle Ages, translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan.

(Oxford: Blackwell, 1993) Saint Louis (Paris: Gallimard, 1996) Saint Francis of Assisi, trans. Christine Rhone

(London: Routledge, 2003) The Birth of Europe, translated by Janet Lloyd.

(Oxford: Blackwell, 2005) In Search of Sacred Time, translated by Lydia G. Cochrane

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014)

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED: There is a good biography of Dante written by the late R. W. B. Lewis, Dante (ISBN 0670899097) and it is excellent and exactly what many of you will want: a short (200 pages), well-written, inexpensive ($19.95) biography of Dante. It is perfect for our course and although I don't want to make it a required book, I am sure that anyone who buys it will be happy they did.

PART TWO: Dante in Verona where he wrote the Purgatory

Week 25: Mon., Apr. 27, 2015

Italy on the Edge; 1348

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 75 to 200 million people and peaking in Europe in the years 1346–53. Although there were several competing theories as to the etiology of the Black Death, analysis of DNA from victims in northern and southern Europe published in 2010 and 2011 indicates that the pathogen responsible was the Yersinia pestis bacterium, probably causing several forms of plague.

The Black Death is thought to have originated in the arid plains of Central Asia, where it then travelled along the Silk Road, reaching the Crimea by 1343.] From there, it was most likely carried by Oriental rat fleas living on the black rats that were regular passengers on merchant ships. Spreading throughout the Mediterranean and Europe, the Black Death is estimated to have killed 30–60% of Europe's total population. In total, the plague reduced the world population from an estimated 450 million down to 350–375 million in the 14th century. The aftermath of the plague created a series of religious, social, and economic upheavals, which had profound effects on the course of European history. It took 150 years for Europe's population to recover.[citation needed] The plague recurred occasionally in Europe until the 19th century. (Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING

The best recent study of the Black Death is this excellent book of 2005 by John Kelly.

John Kelly,

The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death,

Harper Pennial paperback, 2005,

ISBN 0060006935

REVIEW:

Amazon.com Review. A book chronicling one of the worst human disasters in recorded history really has no business being entertaining. But John Kelly's The Great Mortality is a page-turner despite its grim subject matter and graphic detail. Credit Kelly's animated prose and uncanny ability to drop his reader smack in the middle of the 14th century, as a heretofore unknown menace stalks Eurasia from "from the China Sea to the sleepy fishing villages of coastal Portugal [producing] suffering and death on a scale that, even after two world wars and twenty-seven million AIDS deaths worldwide, remains astonishing." Take Kelly's vivid description of London in the fall of 1348: "A nighttime walk across Medieval London would probably take only twenty minutes or so, but traversing the daytime city was a different matter.... Imagine a shopping mall where everyone shouts, no one washes, front teeth are uncommon and the shopping music is provided by the slaughterhouse up the road." Yikes, and that's before just about everything with a pulse starts dying and piling up in the streets, reducing the population of Europe by anywhere from a third to 60 percent in a few short years. In addition to taking readers on a walking tour through plague-ravaged Europe, Kelly heaps on the ancillary information and every last bit of it is captivating. We get a thorough breakdown of the three types of plagues that prey on humans; a detailed account of how the plague traveled from nation to nation (initially by boat via flea-infested rats); how floods (and the appalling hygiene of medieval people) made Europe so susceptible to the disease; how the plague triggered a new social hierarchy favoring women and the proletariat but also sparked vicious anti-Semitism; and especially, how the plague forever changed the way people viewed the church. Engrossing, accessible, and brimming with first-hand accounts drawn from the Middle Ages, The Great Mortality illuminates and inspires. History just doesn't get better than that. --Kim Hughes

RECOMMENDED READING

If you would like to read an account of human beings and disease then this small brilliant book from by the greatest living American historian, William McNeill will serve you well. I say the "greatest living..." and of course that is debatable, but for me, I value what William McNeill has done as the highest achievement in history, especially his masterpiece,The Rise of the West. It is still the best one-volume history of Western Civilization. Plagues and Peoples is a very wide rich book. It begins with a short introduction to the anthropological history of humankind and always with an eye to how disease has played its part. The section of the book that will most interest us this week is Chapter Four: The Impact of the Mongol Empire on Shifting Disease Balances, 1200–1500. This chapter is the best analysis of how the Black Death was connected to larger issues of populations and politics. It is worth owning the book if only to go directly to Chapter 4.

William H. McNeill,

Plagues and Peoples,

Doubleday Anchor paperback, first published in 1976. 2005,

ISBN 0385121229

Amazon.com Review

No small themes for historian William McNeill: he is a writer of big, sweeping books, from The Rise of the West to The History of the World. Plagues and Peoples considers the influence of infectious diseases on the course of history, and McNeill pays special attention to the Black Death of the 13th and 14th centuries, which killed millions across Europe and Asia. (At one point, writes McNeill, 10,000 people in Constantinople alone were dying each day from the plague.) With the new crop of plagues and epidemics in our own time, McNeill's quiet assertion that "in any effort to understand what lies ahead the role of infectious disease cannot properly be left out of consideration" takes on new significance.

From the Publisher

McNeill's highly acclaimed work is a brilliant and challenging account of the effects of disease on human history. His sophisticated analysis and detailed grasp of the subject make this book fascinating reading. By the author of The Rise Of The West. Upon its original publication, Plagues and Peoples was an immediate critical and popular success, offering a radically new interpretation of world history as seen through the extraordinary impact--political, demographic, ecological, and psychological--of disease on cultures. From the conquest of Mexico by smallpox as much as by the Spanish, to the bubonic plague in China, to the typhoid epidemic in Europe, the history of disease is the history of humankind. With the identification of AIDS in the early 1980s, another chapter has been added to this chronicle of events, which William McNeill explores in his new introduction to this updated editon. Thought-provoking, well-researched, and compulsively readable, Plagues and Peoples is that rare book that is as fascinating as it is scholarly, as intriguing as it is enlightening. "A brilliantly conceptualized and challenging achievement" (Kirkus Reviews), it is essential reading, offering a new perspective on human history.

Week 26: Tue., May. 3, 2016

Boccaccio, the Decameron, and the Plague

Giovanni Boccaccio was born in 1313, in the small town of Certaldo which is located just south of Florence in the Val d' Elsa. His father was a merchant-banker and in 1326 the family loved to Naples. IN this huge bustling international city, young Giovanni went to work in his father's bank to learn banking. But he soon realized he cared nothing about business so convinced his father to allow him to enter the University of Naples to study Law. Giovanni cared only a little more about the Law than he did about banking, but he loved the university and used his six years there to acquire a brilliant education. Naples was much more international than Florence with ties to the Islamic work, to Egypt, to Greece, and the Byzantine empire. And so when Giovanni returned to Florence in 1341, he now possessed a sophisticated education that included knowledge of some Greek, and a knowledge of philosophy, law, and literature. During the next six years, Boccaccio wrote a number of works and attempted to create a career in literature. A professional writer at that time relied on patrons. There was no copyright, no income from one's printed works. So the professional writer looked for financial support from various sponsors: political, religious, private. Then the event that would change his life and his career and his fame hit all of Italy: The Black Plague. Florence was hit as hard as any large city. And in months, the population of this city of 100,000 fell by half. Maybe more. Boccaccio saw it all up close, because his father was serving his beloved city as Minister of Supply, with all the responsibilities of trying to help the desperate population. He died the next year worn out by his work for his city. Boccaccio launched the book that would make him famous in 1349, as his family tried to recover from the Pest and from the death of the Patriarch of the family. Boccaccio sat down in 1349 and began to write The Decameron. The success of the book was phenominal. It made its author famous overnight. It is still one of the most popular books ever written in Italian.

RECOMMENDED READING:

This is an excellent edition of selected stories from the Decameron as well as important critical articles from experts on Boccaccio and the most important early biography of him.

Giovanni Boccaccio,

The Decameron (Selections),

translated by Peter Bondanella,

Norton Critical Edition,

ISBN 0393091325

AMAZON REVIEW:

'The Decameron' is a series of 100 stories, ten stories told each night by ten different people who had left the city for a country sojourn to escape a time of plague. Giovanni Boccaccio, an Italian author known as part of the founding trinity of Italian literature (the others are Dante and Petrarca), was born in 1313, and produced most of his literary works by his mid-30s. The ten characters in 'The Decameron' were all young people, much like Boccaccio, and the passions, interests and issues of his own age is illustrated among these folk -- Boccaccio's possibly-fictitious love, Fiammetta, is similarly one of the characters here. This edition by Norton does not include all 100 stories, but rather 21 selected stories, many of the more popular ones, selected by professors Mark Musa and Peter Bondanella (professors at my university when I was there 20 years ago), who are also known for their editing and translation of works by Dante and Machiavelli. There are selections from each 'day' (set of 10 stories), as well as a few of the extra texts, such as a prologue, introduction, and overall conclusion by Boccaccio. These are edited to fit together, as Boccaccio's tales often would wind from one story to the next, making a selection of disconnected stories difficult in transition without editing. There are also two different kinds of critical analytical materials included in this Norton Critical Edition. The first includes personal correspondence samples, particularly between Boccaccio and Petrarca; these date even after the writing of 'The Decameron', showing the interest and reactions. These materials include other contemporary and closely-following generations' reactions and influences from 'The Decameron'.

RECOMMENDED READING

John Kelly,

The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death,

Harper Pennial paperback, 2005,

ISBN 0060006935

REVIEW:

Amazon.com Review. A book chronicling one of the worst human disasters in recorded history really has no business being entertaining. But John Kelly's The Great Mortality is a page-turner despite its grim subject matter and graphic detail. Credit Kelly's animated prose and uncanny ability to drop his reader smack in the middle of the 14th century, as a heretofore unknown menace stalks Eurasia from "from the China Sea to the sleepy fishing villages of coastal Portugal [producing] suffering and death on a scale that, even after two world wars and twenty-seven million AIDS deaths worldwide, remains astonishing." Take Kelly's vivid description of London in the fall of 1348: "A nighttime walk across Medieval London would probably take only twenty minutes or so, but traversing the daytime city was a different matter.... Imagine a shopping mall where everyone shouts, no one washes, front teeth are uncommon and the shopping music is provided by the slaughterhouse up the road." Yikes, and that's before just about everything with a pulse starts dying and piling up in the streets, reducing the population of Europe by anywhere from a third to 60 percent in a few short years. In addition to taking readers on a walking tour through plague-ravaged Europe, Kelly heaps on the ancillary information and every last bit of it is captivating. We get a thorough breakdown of the three types of plagues that prey on humans; a detailed account of how the plague traveled from nation to nation (initially by boat via flea-infested rats); how floods (and the appalling hygiene of medieval people) made Europe so susceptible to the disease; how the plague triggered a new social hierarchy favoring women and the proletariat but also sparked vicious anti-Semitism; and especially, how the plague forever changed the way people viewed the church. Engrossing, accessible, and brimming with first-hand accounts drawn from the Middle Ages, The Great Mortality illuminates and inspires. History just doesn't get better than that. --Kim Hughes

This two-volume history of Florence is the best detailed study of Florence ever written. Schevill wrote a masterpiece of well researched narrative history for Florence in 1936 and then it was republished in a Harper Torchbook paperback in 1961. The Harper Torchbook is still out there in used book stores so we have purchased five for our library. But there are still copies left if you want to own one. It is two volumes with the first volume devoted to our period of Medieval History and the second volume on Renaissance Florence. For the Lombards see Medieval Florence (Volume 1) Chapter Three, "Darkness Over Florence."

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU

Week 27: Tue., May. 10, 2016

Painting in Italy After the Black Death

During the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Italian painters pursued a common goal. Each new generation explored ways to portray the human being in a more and more true to life style. each generation explored ways to portray the physical space in which the human being dwells in a more and more realistic way. Rooms became deeper, floors and ceilings helped define interior space, space developed a more three-dimensional appearance. Each new generation explored the creation of this rich new world in which human bodies were solid and sometimes beautiful, and rooms and houses and spaces took on a solid deep reality. The result was such that by 1340 in the work of Giotto and his followers, Italian painters had created a style of painting like nothing that ever been seen before: not in Greece, not in Rome. Human beings had grace and substance and stood solid on the ground. The countryside unwound in beautiful colorful vistas. A kind of soft calm settled over the streets and houses of Italy in 1340. Then disaster struck. Just at the moment that Giotto and his colleagues were creating this rich new world, the Black Plague struck. And nothing was the same after. Millard Meiss noticed all this and in a groundbreaking book, he pointed to the drastic change in the painting of Florence and Siena after the Black Death and that will be our subject tonight.

RECOMMENDED READING

The book noted below is the basis for our lecture tonight. The author of the book, Millard Meiss, a Princeton university art historian, wrote one of the great books of all time in the field of art history when he explored the relationship between the Black Death and painting. It was a brilliant idea and he found evidence to support his theory that the Black Death had changed the whole society and that one change was evident in the painting done in the years immmediately succeeding the Black Death. Used copies are available at Amazon.

About Millard Meiss: Millard Meiss (March 25, 1904 - June 12, 1975) was an American art historian, one of whose specialties was Gothic architecture. A professor at Princeton University, among his many important contributions are Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death and French Painting in the Time of Jean de Berry. He organized the first meeting in the United States of the Congress of the International Committee of the History of Art, and was elected the organization's president. In 1966, he assisted in Florence with restoration efforts following the 1966 Flood of the Arno River, despite being in ill health.

Unfortunately for us, this is such a popular book even many yeara after its initial publication that the price for a new paperback is high. But there are many used copies at good prices. If you pay $10.00 you get a copy described as very good.

Millard Meiss,

Painting in Florence and Siena After the Black Death,

Princeton University Press, 1979,

ISBN 0691003122

John Kelly,

The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death,

Harper Pennial paperback, 2005,

ISBN 0060006935

REVIEW:

Amazon.com Review. A book chronicling one of the worst human disasters in recorded history really has no business being entertaining. But John Kelly's The Great Mortality is a page-turner despite its grim subject matter and graphic detail. Credit Kelly's animated prose and uncanny ability to drop his reader smack in the middle of the 14th century, as a heretofore unknown menace stalks Eurasia from "from the China Sea to the sleepy fishing villages of coastal Portugal [producing] suffering and death on a scale that, even after two world wars and twenty-seven million AIDS deaths worldwide, remains astonishing." Take Kelly's vivid description of London in the fall of 1348: "A nighttime walk across Medieval London would probably take only twenty minutes or so, but traversing the daytime city was a different matter.... Imagine a shopping mall where everyone shouts, no one washes, front teeth are uncommon and the shopping music is provided by the slaughterhouse up the road." Yikes, and that's before just about everything with a pulse starts dying and piling up in the streets, reducing the population of Europe by anywhere from a third to 60 percent in a few short years. In addition to taking readers on a walking tour through plague-ravaged Europe, Kelly heaps on the ancillary information and every last bit of it is captivating. We get a thorough breakdown of the three types of plagues that prey on humans; a detailed account of how the plague traveled from nation to nation (initially by boat via flea-infested rats); how floods (and the appalling hygiene of medieval people) made Europe so susceptible to the disease; how the plague triggered a new social hierarchy favoring women and the proletariat but also sparked vicious anti-Semitism; and especially, how the plague forever changed the way people viewed the church. Engrossing, accessible, and brimming with first-hand accounts drawn from the Middle Ages, The Great Mortality illuminates and inspires. History just doesn't get better than that. --Kim Hughes

Week 28: Tue., May. 17, 2016

Too Many Popes

In Week 22, we studied the Papacy in Avignon. The popes stayed in Avignon from 1305 to 1382. By 1382, many in the church were aware that the continued French residency of the popes was damaging the international Christian church and so they began to organize to try to bring back the popes to Rome. Petrarch was one influential leader in this movement. He went to Avignon and begged the pope to bring the papacy back to Rome. Finally, on September 13, 1376, Gregory XI abandoned Avignon and moved his court to Rome (arriving on January 17, 1377), officially ending the Avignon Papacy. On April 16, 1378, a College of Cardinals in Rome chose an Italian, Bartolomeo Prignano, as Pope Urban VI. Urban turned out to be a terrible diplomat and a bullheaded leader who angered all the Frenchmen. One night they slipped out of Rome and traveled back to France where they elected a new French Pope: In 1382, an international effort led to the election of an Italian, Benedetto.....to the Papal Throne, and he promised to restore both the city and the institution to its former glory. But he alienated everyone and the French cardinals escaped Rome into he night, and elected one of their own as a new pope, Pope Clement VII, and now there were two popes. The Papal Schism of Europe. And it was going to get worse. The Papal Schism of the fourteenth century did terrible damage to the Papacy in the eyes of the faithful. The one greatest virtue that the Papal leader had always possessed was that he was the one true apostolic successor to Jesus. For 1300 years, pope after pope had been elected without interruption, to sit on the seat of St Peter. But with the outbreak of Schism, that claim was now laid bare. And everyone began to wonder whether the Papacy itself was flawed and worthless. Some suggested that maybe we did not need a Pope!

RECOMMENDED READING

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU

Week 29: Tue., May. 24, 2016

Islam and Christianity in the 14th Century

During week 29 we want to look at the changing relationship of Islam and Christianity in the Mediterranean and especially in Italy. The 600 years between the Islamic invasion of Spain and the last Crusade witnessed a change in fortunes for the two sides of the confrontation between Muslims and Christians.

In 711, Cristendom was disorganized, attacked from all sides by various invading peoples, and lacking any central authority. By 1300, Italy was rich and successful. The enemy across the seas was less frightening than in the days when Islamic ships sailed right up the Tiber river to the Vatican. As Europe gained confidence, it also gained intellectual confidence. This new confidence allowed European professors, philosophers, doctors, and and artists to examine with a more open attitude the knowledge held in the Islamic societies.

RECOMMENDED READING

This is the best one-volume introduction to Islam.

Bernard Ellis Lewis,

Islam: The Religion and the People,

Pearson Prentice Hall; 1 edition (August 29, 2008),

ISBN 0132230852

Praise for Bernard Lewis:

"For newcomers to the subject, Bernard Lewis is the man." TIME Magazine

“The doyen of Middle Eastern studies." The New York Times

“No one writes about Muslim history with greater authority, or intelligence, or literary charm.” British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper.

This is the best one-volume study of Christian-Islam relations in the Middle Ages and it is especially excellent on Spain. Disregard the bizarre user reviews on Amazon. Most of them seem to be motivated by contemporary politcal issues rather than Wheatcroft's excellent history.

Andrew Wheatcroft,

Infidels: A History of the Conflict Between Christendom and Islam,

Random House paperback, 2003,

ISBN 0812972392

From Booklist

*Starred Review* In the roar of skyscrapers collapsing in New York and in the thunder of fusillades in Afghanistan and Iraq, a leading British historian hears echoes of battles fought centuries ago. This timely chronicle amplifies those echoes to show how much ancient animosities pervade the modern conflict between radical Islamic terrorist Osama bin Laden and America. Impelling the Muslim and Christian combatants who crossed swords at Jerusalem and Granada, at Lepanto, Constantinople, and Missolonghi, these ancient hatreds inspired daring innovations in military weaponry and tactics, as well as astonishing enlargements in both faiths' religious demonology. Wheatcroft recounts the clashes of arms--jihad and crusade--in narrative taut and memorable. With rare sophistication, he also traces the perplexing ways religious orthodoxy now reinforced, now checked the political and economic impulses shaping Europe and the Levant. But readers will praise Wheatcroft most for his acute psychological analysis of how Muslim and Christian leaders alike imbued their followers with hostility toward those who adhered to alien creeds. It is this analysis that lends force to the concluding commentary on how President Bush has unwittingly tapped into a very old reservoir of religious enmity with his absolutist rhetoric calling for a "crusade" against the terrorist evil. As a work that interprets today's headlines within a very long chronology, this book will attract a large audience. Bryce Christensen Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved.

Week 30: Tue., May. 31, 2016

Retrospective on the Art of the Middle Ages

In our last class meeting of our study of Medieval Italy, we will look back on the whole story of art from the Fall of Rome to the dawn of the Renaissance in 1400. We will look back at all three arts: painting, sculpture, and architecture, and we will see how Italy changed the look of Western Art in this one thousand years.