Week 11

Week 11: Wednesday, January 11, 2023

The Year One Thousand

Week 11

Something near miraculous happened around the year 1000 in Europe. It was almost as if people were energized by the very year itself, the historic moment, a millennium since the Crucifixion. Whatever the motivation, on or about 1000 the international economy exploded with international trade being released by new peace in the Mediterranean. And as a result of all this new trade, certain cities like Pisa and Venice benefited immediately and were able to begin building two of the greatest cathedrals in Europe. The new "Romanesque" style came out of the situation in which a newly rich European society needed an artistic style. and ready at hand was the old Roman style. Roman ruins sat all around Italy, Spain and France. It was easy to imitate or revise this Roman style. And thus was born "Romanesque" a name invented by nineteenth-century art historians. Romanesque spread all over Europe and became the first great international style since the fall of Rome in circa 400 AD. Below you see the facade of the church of Pieve di Santa Maria, one of the purest examples you could ever see of Romanesque. As you can see, the decoration of the front of the church is pure Roman arcade: three rows of gorgeous Roman arches which were copied off of some Roman arch or Roman sarcophagus sitting around Arezzo.

RECOMMENDED TEXTBOOK FOR THE YEAR

There are three major books to use in a history of art class by authors Helen Gardner, H. W. Janson, and Hugh Honour. We are recommending that if you are purchasing a book for the year, then get Hugh Honour and John Fleming's The Visual Arts: A History. It is a beautiful book. It has a reasonable price. And it is available. And it is a great history of art.

12

Week 12: Wednesday, January 18, 2023

Paris: Notre Dame

Week 12

Something completely new emerged in Paris in the 12th Century: Gothic art. This new style was first seen at the church of Saint Denis in the north edge of Paris, the church dedicated to the patron saint of France. Saint Denis became the first bishop of Paris. He was decapitated on the hill of Montmartre in the mid-third century with two of his followers, and is said to have subsequently carried his head to the site of the current church, indicating where he wanted to be buried. Here in 1144, the King and Queen of France, Louis VII and his brilliant wife Eleanor of Aquitaine presided over the dedication of this new church to Saint Denis. Within the church were seen the first Gothic arches ever built in Europe. Something new was being created here. The new style turned away from the old down to earth Roman arches of Romanesque and reached for the sky with soaring pointed arches and flying buttresses that allowed the new churches to go higher and higher. What drove this new style? Mary, the mother of Jesus, Mary the blessed mother, was the inspiration. All of a sudden, the whole of European Christianity changed. What had been a religion of sin and judgement suddenly became a new religion of celebration, of an embrace of life and love, of the celebration of the beauty of nature. Painting and sculpture exploded with a new life, new color, new forms. Look at these beautiful forms of Adam and Eve on the facade of Notre Dame. Beautiful trees and leaves and bodies.

RECOMMENDED READING

Hugh Honour discusses medieval art in chapter 9, beginning on page 356.

For the Gothic cathedral, see page 378.

13

Week 13: Wednesday, January 25, 2023

Dante and Art

Week 13

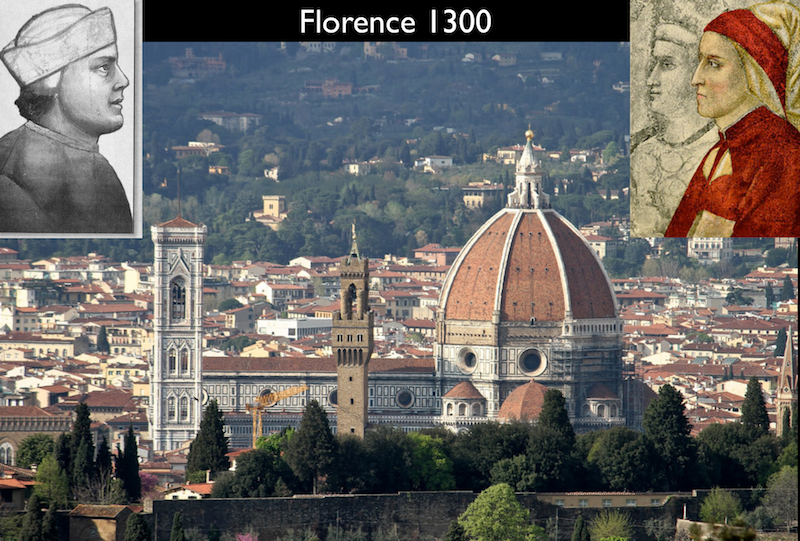

Dante wrote the greatest work of literature of the Middle Ages. His work in three parts (Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso) summarized the attitudes of all of Europe at the beginning of the 14th Century. For the first half of the 14th Century, Europe was swept up in an optimistic, hopeful vision of the future with growth, economic well being, expansion of trade, and expansion of the population. His city of Florence reached 100,000, its peak until it reached that number again in the 19th Century. The trinitarian view of the world and the optimistic view of that world expressed in his poem was totally destroyed when the Black Death arrived in 1348. But for those first 48 years, Europe and especially Italy was the center of a growing creative society. Two great artists, one in Florence -- Giotto, and one in Siena -- Duccio, gave human forms and stories in their spectacular achievements at about 1310. This evening we will spend some time on these visions and their inspiration, Dante Alighieri.

RECOMMENDED READING

14

Week 14: Wednesday, February 1, 2023

The Black Death

Week 14

In early October 1347, twelve Genoese galleys put in at the port of Messina in Sicily. The town was one of the principal stopping-off points on the lucrative trade route from the East that brought silks and spices along the Old Silk Road, through the Crimea, across the Black Sea and into Europe. On this occasion, however, no silks or spices were to be unloaded from the vessels, which had probably come from the trading stations Genoa maintained at Tana and Kaffa on the north coast of the Black Sea. The port authorities found, to their horror, that scarcely anyone onboard the twelve galleys was left alive, and those who were exhibited a pronounced lethargy and a strange sickness 'that seemed to cling to their very bones'. They suffered from black boils and everything that came out of their bodies – breath, blood, pus – smelled awful. The presence of the galleys was deemed a public health emergency of the first order and, within a day or so, the galleys were driven from the port, so afraid were the Messinese of what they found on board the Genoese vessels. Although the measures were understandably protective, it was too late: the sickness the Genoese crewmen were suffering from took hold of the town within a few days. The doomed galleys drifted on, infecting all who came into contact with them. The Black Death had arrived in Europe. This was not the first time the plague had struck. The town elders and physicians in Messina may well have known – after either hearing eyewitness reports or venturing, almost certainly suicidally, onto the Genoese boats – what the sailors were dying from. There had been outbreaks of plague for generations, usually sporadic and confined to localised areas, lasting a few months, but deadly nonetheless. It had attacked Frederick Barbarossa's army outside Rome in 1167, before it became rife in the city itself, where it recurred in 1230. It had also attacked Florence in 1244, and the south of France and Spain in 1320 and 1333. This time, however, it would be different. This time the plague would not be confined to one or two towns, but would spread unpredictably and, at times it seemed, uncontrollably, across the whole continent, taking rich and poor to their graves in the worst single epidemic in history. But in October 1347, as the Messinese died screaming in their homes and in the streets from what seemed like a Divine punishment, the wider world must have been the last thing on their minds. The experience of the Black Death coming at midpoint in the 14th century changed the whole vision of life and art forever.

RECOMMENDED READING

Barbara Tuchman,

A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century,

Random House Trade Paperbacks; Reissue edition (July 12, 1987),

ISBN 0345349571

This is the best book in English on the 14th Century and I can't imagine anyone will ever write a better one. Barbara Tuchman was a miracle in the history world. She had no special training; she was just a Manhattan housewife who loved history. One day she walked down Fifth Avenue to the New York Public Library. She began to read and soon began to write and was soon into a spectacular career as an international best-selling author. She wrote five of the best books ever written in the field. Her masterpiece is A Distant Mirror on the 14th Century. She takes one character, Enguerand de Coucy, a French noble whose life touched almost everyone important in the century, and then she takes us all through the stories of the incredible century. History has never been better. It is like a novel; only better. You can read it on paper, in Kindle, or on audible.

Amazon Comment:

In this sweeping historical narrative, Barbara Tuchman writes of the cataclysmic 14th Century, when the energies of medieval Europe were devoted to fighting internecine wars and warding off the plague. Some medieval thinkers viewed these disasters as divine punishment for mortal wrongs; others, more practically, viewed them as opportunities to accumulate wealth and power. One of the latter, whose life informs much of Tuchman's book, was the French nobleman Enguerrand de Coucy, who enjoyed the opulence and elegance of the courtly tradition while ruthlessly exploiting the peasants under his thrall. Tuchman looks into such events as the Hundred Years War, the collapse of the medieval church, and the rise of various heresies, pogroms, and other events that caused medieval Europeans to wonder what they had done to deserve such horrors.

Reviews:

“Beautifully written, careful and thorough in its scholarship . . . What Ms. Tuchman does superbly is to tell how it was. . . . No one has ever done this better.”—The New York Review of Books

“A beautiful, extraordinary book . . . Tuchman at the top of her powers . . . She has done nothing finer.”—The Wall Street Journal

“Wise, witty, and wonderful . . . a great book, in a great historical tradition.”—Commentary

From the Publisher:

Anyone who has read The Guns of August or Stilwell and the American Experience in China, knows that Barbara Tuchman was one of the most gifted American writers of this century. Her subject was history, but her profiles of great men and great events are drawn with such power that reading Tuchman becomes a riveting experience. In A Distant Mirror, Barbara Tuchman illuminates the Dark Ages. Her description of medieval daily life, the role of the church, the influence of the Great Plagues, and the social and political conventions that make this period of history so engrossing, are carefully woven into an integrated narrative that sweeps the reader along. I am a particular devotee of medieval and pre-Renaissance music, so Barbara Tuchman's brilliant analysis of this period has special meaning for me—and I hope for many others. —George Davidson, Director of Production, The Ballantine Publishing Group

About the Author:

Barbara W. Tuchman (1912–1989) achieved prominence as a historian with The Zimmermann Telegram and international fame with The Guns of August—a huge bestseller and winner of the Pulitzer Prize. Her other works include Bible and Sword, The Proud Tower, Stilwell and the American Experience in China (for which Tuchman was awarded a second Pulitzer Prize), Notes from China, A Distant Mirror, Practicing History, The March of Folly, and The First Salute.

15

Week 15: Wednesday, February 8, 2023

The Renaissance in Florence

Week 15

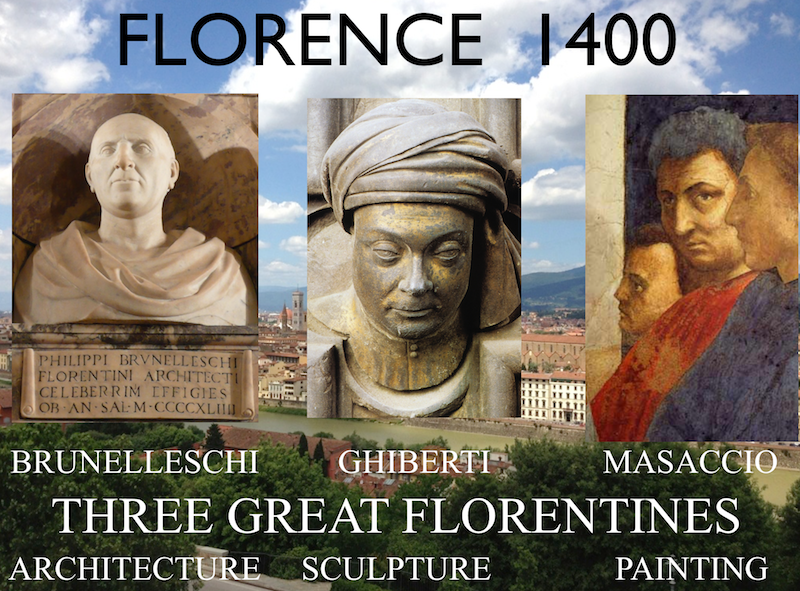

In 1390, Manuel Chrysoloras (1355-1415) came to Venice on a diplomatic errand as the representative of the Byzantine emperor in Constantinople. While visiting Venice he met a number of Florentines and one, Giacomo da Scarperia, followed him home to Constantinople to study Greek. Other Florentines heard about Chrysoloras and therefore in 1396, the Florentine Chancellor Coluccio Salutati invited Chrysoloras to come to Florence as a professor of Greek. Chrysoloras would teach the ancient language to whomever might want to attend the classes. This event—a formal program of Europeans studying Greek—is as useful a mark for the beginning of the Renaissance as any. With the arrival of Chrysoloras in Florence, almost a thousand years of Western European ignorance of Greek came to an end. And with this new field of study came new books, new publications, new ideas. The study of Greek sparked new interest in mathematics, astronomy, geography, geometry, optics, and cartography. By the 1420’s Florence found itself the center of an international movement that would help to create modern Europe.

RECOMMENDED READING

J. H. Plumb,

The Italian Renaissance,

Mariner Books; Revised edition (June 19, 2001),

ISBN 0618127380

Amazon: Spanning an age that witnessed great achievements in the arts and sciences, this definitive overview of the Italian Renaissance will both captivate ordinary readers and challenge specialists. Dr. Plumb’s impressive and provocative narrative is accompanied by contributions from leading historians, including Morris Bishop, J. Bronowski, Maria Bellonci, and many more, who have further illuminated the lives of some of the era’s most unforgettable personalities, from Petrarch to Pope Pius II, Michelangelo to Isabella d'Este, Machiavelli to Leonardo. A highly readable and engaging volume, THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE is a perfect introduction to the movement that shaped the Western world.

A useful book this week is the brilliant The Italian Renaissance by J. H. Plumb. This is a wonderful and succinct introduction to the Renaissance by one of our greatest historians, J. R. Plumb.

This is a wonderful book that is perfect for us as we spend a week talking about Brunelleschi and Renaissance Florence. I highly recommend it to you all. And now it is available in paperback ($13.00).

About the Author

Born and raised in Canada, Ross King has lived in England since 1992. In 2002―03, two books of his were published in the United States, Domino, about the world of masquerades and opera in 18th century London and the New York Times bestselling Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling. Nominated for a National Book Critics Circle Award in 2003 in the category of critisicm, in Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling King tells the story of the four years―1508-1512.―Michelangelo spent painting the ceiling of the newly restored Sistine chapel. In this extraordinary book, he presents a magnificent tapestry of day-to-day life of the ingenious Sistine scaffolding and outside in the upheaval of early 16th century Rome. King’s highly acclaimed Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture, was an instant hit in the U.S., landing on the New York Times, Boston Globe and San Francisco Chronicle bestseller lists and becoming a handselling favorite among booksellers. Brunelleschi’s Dome was chosen "The 2000 Book Sense Nonfiction Book of the Year" and a Book Sense 76 top ten selection. Anyone familiar with Ross King’s writing knows that he has an astonishing knowledge of European cultural history. He originally planned a career in academia, earning his Ph.D. in English Literature and moving to England to assume a research position at the University of London. King lives near Oxford, England, in the historic town of Woodstock, the site of Blenheim Palace. He is a devoted cyclist and hikes regularly in both the Pyrenees and the Canadian Rockies.

RECOMMENDED TEXTBOOK FOR THE YEAR

For the Renaissance in Florence see Honour, Chapter 10, beginning p. 416.

16

Week 16: Wednesday, February 15, 2023

1500 in Milan

Week 16

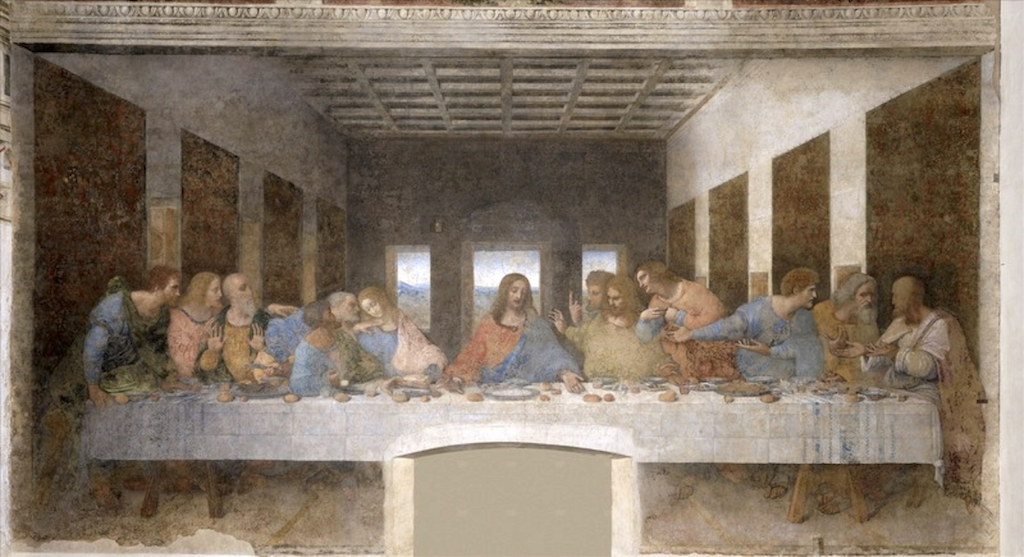

In 1500, the world began to travel to Milan to see this incredible new painting that had been unveiled in 1498 and was already being called "the greatest painting in the world." Leonardo da Vinci from Tuscany was now world famous for the extraordinary fresco on the wall of the refectory of the convent church of Santa Maria Delle Grazie. At this moment three great painters were spreading the fame of Florence: Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael, all of whom were working together in the city by the Arno. The Last Supper by Leonardo in Milan is one of the world's most famous paintings, and one of the most studied and scrutinized. The painting represents the scene of the Last Supper of Jesus with his disciples, as it is told in the Gospel of John 13: 21. Leonardo specifically portrays the varying degree of anger and shock of each apostle when Jesus said one of them would betray him. The apostles have been identified from a manuscript by Leonardo found in the 19th Century (before then only Judas, Peter, John, and Jesus were positively identified). The Last Supper is not a true fresco: Because Leonardo sought greater detail and luminosity than could be achieved with traditional fresco (which cannot be modified as the artist works), he painted The Last Supper on a dry wall, then added an undercoat of white lead to enhance the brightness of the oil and tempera that was applied on top. These techniques were important for Leonardo's desire to work slowly on the painting, giving him sufficient time to develop the gradual shading or chiaroscuro that was essential to his style. Unfortunately though, due to Leonardo’s methods, the painting began deteriorating almost immediately. Environmental conditions and the ravages of wars have also threatened the painting. The most recent of numerous restorations was completed in 1999 after 21 years of painstaking labor.

RECOMMENDED READING

Walter Isaacson,

Leonardo da Vinci,

Simon & Schuster; 1st Edition (October 17, 2017),

ISBN 1501139150

Editorial Reviews:

"As always, [Isaacson] writes with a strongly synthesizing intelligence across a tremendous range; the result is a valuable introduction to a complex subject. . . . Beneath its diligent research, the book is a study in creativity: how to define it, how to achieve it. . . . Most important, Isaacson tells a powerful story of an exhilarating mind and life." —The New Yorker

“To read this magnificent biography of Leonardo da Vinci is to take a tour through the life and works of one of the most extraordinary human beings of all time and in the company of the most engaging, informed, and insightful guide imaginable. Walter Isaacson is at once a true scholar and a spellbinding writer. And what a wealth of lessons there are to be learned in these pages." —David McCullough, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Wright Brothers and 1776

“I’ve read a lot about Leonardo over the years, but I had never found one book that satisfactorily covered all the different facets of his life and work. Walter—a talented journalist and author I’ve gotten to know over the years—did a great job pulling it all together. . . . More than any other Leonardo book I’ve read, this one helps you see him as a complete human being and understand just how special he was.” —Bill Gates

For Leonardo in Milan, see Honour, pages 466-469.

17

Week 17: Wednesday, February 22, 2023

1500 in Florence

Week 17

In the first decade of the 16th Century, Renaissance Florence reached a kind of peak of political creativity with their brilliant Secretary of State Niccolo Machiavelli, its wise leader Piero Soderini, and its youthful sculptor Michelangelo Buonarotti who was about to achieve international stardom with his new work David (1504). The more than 20 foot high David symbolized the courage of the little republic within the international big boys such as Milan and Naples. David stood up to the Goliaths of the world, and Florentines proudly displayed the new work when it was finished in 1504. the committee that decided where to put David include Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci. The civic pride, the artistic pride, that all of Florence felt when David was put on display, signals a kind of summit of Renaissance idealism. The Florence's Renaissance philosophers believed that Christian piety and Classical rationalism could be combined to create a new modern civic culture. Unfortunately, the city would soon learn that by the 1500's what mattered most was power -- brute military power. But for one shining moment, Florence enjoyed international respect for its government, its literature, and its art.

RECOMMENDED READING

For Michelangelo in Florence, see Hugh Honour, pages 474-483.

A NEW BIOGRAPHY OF MICHELANGELO

Antonio Forcellino,

Michaelangelo: A Tormented Life,

Polity; 1st Edition (October 10, 2011),

ISBN 0745640060

18

Week 18: Wednesday, March 1, 2023

Raphael in Rome

Week 18

In the second decade of the 16th Century, the most celebrated and beloved painter in the capital of the Christian church was Raphael Sanzio from the small town of Urbino. Raphael had just spent a exciting period in Florence painting there at the same time as Leonardo and Michelangelo and now he was working for Pope Leo XIII, the Medici Pope Giovanni de' Medici. Pope Leo adored Raphael and gave him some of the greatest honors in the city. He showered rewards on the humble but very handsome young man. And all the city beat a pathway to his door, importuning him to paint a portrait or a mythological scene. Raphael was now finishing something he had begun in 1512 for the previous pope, Pope Julius II, Giovanni della Rovere. And as he labored on his painting of Greek philosophy in the papal apartments, Michelangelo worked next door on the Sistine ceiling. The fresco painting upon which Raphael was working would turn out to be his most famous creation and still is known now with the name the public attached to it when it was unveiled in 1512 -- The School of Athens.

RECOMMENDED READING

For Raphael in Rome, see Hugh Honour, pages 469-482. He discusses both Michelangelo and Raphael since they are both working for Pope Julius at the same time in the same building.

19

Week 19: Wednesday, March 8, 2023

Giorgio Vasari and the New Fame of Artists

Week 19

Giorgio Vasari, born July 30, 1511 in Arezzo, was an Italian painter, architect, writer, and historian, best known for his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, considered the ideological foundation of art-historical writing. He was also the first to use the term "Renaissance" in print. He was born prematurely in Arezzo, Tuscany. Recommended at an early age by his cousin Luca Signorelli, he became a pupil of Guglielmo da Marsiglia, a skillful painter of stained glass. Sent to Florence at the age of sixteen by Cardinal Silvio Passerini, he joined the circle of Andrea del Sarto and his pupils Rosso Fiorentino and Jacopo Pontormo, where his humanist education was encouraged. He was befriended by Michelangelo, whose painting style would influence his own. He died on 27 June 1574 in Florence, Grand Duchy of Tuscany, aged 62. Vasari had immense influence on art and art history. His book with artist biographies came along at midcentury when the art of printing had advanced and when publishers could include woodcuts in the printed book-portraits of the various artists. Thus Vasari's book was the first to allow readers to have an impression of not only the stories of the artists, but also their appearance. The book had an incredible success. Edition after edition was printed. Overall, the Lives of the Artists changed the public's impression of art and artists forever. Before Vasari, artists had been thought of as glorified craftsmen. After Vasari, artists came to be seen in the public's eye as enabled, special, gifted. This impression was advanced above all due to the picture Vasari painted of his friend Michelangelo. Vasari turned Michelangelo into someone nearly divine. By 1600, thanks to Vasari artists were no longer just clever workers. Now they were special, unique, worthy of great rewards and lavish life styles.

See below the interior of one of the rooms of Vasari's beautiful villa in Arezzo.

RECOMMENDED READING

While this is just volume 1 of his series, if you want volume 2, it is available also.

Institute Library Call Number: 709.2 Vas LIV Bon

Two copies in our library (but not same edition as above).

20

Week 20: Wednesday, March 15, 2023

Modernity

Week 20

In the late 1500's people began to use a new word -- modern. It appeared in all languages but the earliest were in Italian and English -- "moderno" and "modern." But soon all European languages produced their versions of this new word. The sudden success of the word around 1600 revealed that people all over Europe felt the need to distinguish their times with a new descriptive term. The word had first appeared in Italy back in the days of Francesco Petrarca and Boccacio. Both had used the word. But obviously, the Black Death threw off all language and all thinking so the word languished for a while. But in the early 1600's people felt they were living in new times -- times that needed a new word. And so was born "modern." By the third quarter of the 17th Century, a German historian writing a world history textbook for high school students produced a history in three volumes and called them Ancient, Medieval, and Modern. And so was born the tripartite description we all use every day. The Modern Age was born, and most saw its birthday as maybe January 1, 1600. The artist who most perfectly captured this birthday occasion was an Italian named Michelangelo da Merisi. He came from a small town outside of Milan, and when he was old enough he went to Milan to study art, then went off to Rome to seek fame and fortune. In Rome, he came to be known by the name of his natal hometown -- Caravaggio. The work of Caravaggio would explode onto the tired old art scene of Italy at the turn of the century. What he did was to clear away all the old cobwebs, the old traditions of what a painting should look like, the old ideas about proper subject matter and proper treatment of the subject matter. He was the walking embodiment of the word "modern." Now when we use that word, we mean modern in the way it was seeing 1600 not in the way it would be used 300 years later with Picasso and Matisse. They were part of "Modernism," i.e. the most modernist you could be. But certainly Caravaggio was modern and revolutionary in his times. But other people were modern too like Galileo and Newton and others who were writing the book on "modern." And other artists such as Vermeer and Velazquez were going to write their own versions of "modern." Below see an example of what paintings looked like before Caravaggio.

RECOMMENDED READING

Andrew Graham-Dixon,

Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane,

W. W. Norton & Company; 1 edition (November 12, 2012),

ISBN 9780393343434

Now look at what paintings looked like after Caravaggio showed everyone how to do it -- simple, clear, common people, common actions, simple clothes.

All

Week 11: Wed., Jan. 11, 2023

The Year One Thousand

Week 11

Something near miraculous happened around the year 1000 in Europe. It was almost as if people were energized by the very year itself, the historic moment, a millennium since the Crucifixion. Whatever the motivation, on or about 1000 the international economy exploded with international trade being released by new peace in the Mediterranean. And as a result of all this new trade, certain cities like Pisa and Venice benefited immediately and were able to begin building two of the greatest cathedrals in Europe. The new "Romanesque" style came out of the situation in which a newly rich European society needed an artistic style. and ready at hand was the old Roman style. Roman ruins sat all around Italy, Spain and France. It was easy to imitate or revise this Roman style. And thus was born "Romanesque" a name invented by nineteenth-century art historians. Romanesque spread all over Europe and became the first great international style since the fall of Rome in circa 400 AD. Below you see the facade of the church of Pieve di Santa Maria, one of the purest examples you could ever see of Romanesque. As you can see, the decoration of the front of the church is pure Roman arcade: three rows of gorgeous Roman arches which were copied off of some Roman arch or Roman sarcophagus sitting around Arezzo.

RECOMMENDED TEXTBOOK FOR THE YEAR

There are three major books to use in a history of art class by authors Helen Gardner, H. W. Janson, and Hugh Honour. We are recommending that if you are purchasing a book for the year, then get Hugh Honour and John Fleming's The Visual Arts: A History. It is a beautiful book. It has a reasonable price. And it is available. And it is a great history of art.

Week 12: Wed., Jan. 18, 2023

Paris: Notre Dame

Week 12

Something completely new emerged in Paris in the 12th Century: Gothic art. This new style was first seen at the church of Saint Denis in the north edge of Paris, the church dedicated to the patron saint of France. Saint Denis became the first bishop of Paris. He was decapitated on the hill of Montmartre in the mid-third century with two of his followers, and is said to have subsequently carried his head to the site of the current church, indicating where he wanted to be buried. Here in 1144, the King and Queen of France, Louis VII and his brilliant wife Eleanor of Aquitaine presided over the dedication of this new church to Saint Denis. Within the church were seen the first Gothic arches ever built in Europe. Something new was being created here. The new style turned away from the old down to earth Roman arches of Romanesque and reached for the sky with soaring pointed arches and flying buttresses that allowed the new churches to go higher and higher. What drove this new style? Mary, the mother of Jesus, Mary the blessed mother, was the inspiration. All of a sudden, the whole of European Christianity changed. What had been a religion of sin and judgement suddenly became a new religion of celebration, of an embrace of life and love, of the celebration of the beauty of nature. Painting and sculpture exploded with a new life, new color, new forms. Look at these beautiful forms of Adam and Eve on the facade of Notre Dame. Beautiful trees and leaves and bodies.

RECOMMENDED READING

Hugh Honour discusses medieval art in chapter 9, beginning on page 356.

For the Gothic cathedral, see page 378.

Week 13: Wed., Jan. 25, 2023

Dante and Art

Week 13

Dante wrote the greatest work of literature of the Middle Ages. His work in three parts (Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso) summarized the attitudes of all of Europe at the beginning of the 14th Century. For the first half of the 14th Century, Europe was swept up in an optimistic, hopeful vision of the future with growth, economic well being, expansion of trade, and expansion of the population. His city of Florence reached 100,000, its peak until it reached that number again in the 19th Century. The trinitarian view of the world and the optimistic view of that world expressed in his poem was totally destroyed when the Black Death arrived in 1348. But for those first 48 years, Europe and especially Italy was the center of a growing creative society. Two great artists, one in Florence -- Giotto, and one in Siena -- Duccio, gave human forms and stories in their spectacular achievements at about 1310. This evening we will spend some time on these visions and their inspiration, Dante Alighieri.

RECOMMENDED READING

Week 14: Wed., Feb. 1, 2023

The Black Death

Week 14

In early October 1347, twelve Genoese galleys put in at the port of Messina in Sicily. The town was one of the principal stopping-off points on the lucrative trade route from the East that brought silks and spices along the Old Silk Road, through the Crimea, across the Black Sea and into Europe. On this occasion, however, no silks or spices were to be unloaded from the vessels, which had probably come from the trading stations Genoa maintained at Tana and Kaffa on the north coast of the Black Sea. The port authorities found, to their horror, that scarcely anyone onboard the twelve galleys was left alive, and those who were exhibited a pronounced lethargy and a strange sickness 'that seemed to cling to their very bones'. They suffered from black boils and everything that came out of their bodies – breath, blood, pus – smelled awful. The presence of the galleys was deemed a public health emergency of the first order and, within a day or so, the galleys were driven from the port, so afraid were the Messinese of what they found on board the Genoese vessels. Although the measures were understandably protective, it was too late: the sickness the Genoese crewmen were suffering from took hold of the town within a few days. The doomed galleys drifted on, infecting all who came into contact with them. The Black Death had arrived in Europe. This was not the first time the plague had struck. The town elders and physicians in Messina may well have known – after either hearing eyewitness reports or venturing, almost certainly suicidally, onto the Genoese boats – what the sailors were dying from. There had been outbreaks of plague for generations, usually sporadic and confined to localised areas, lasting a few months, but deadly nonetheless. It had attacked Frederick Barbarossa's army outside Rome in 1167, before it became rife in the city itself, where it recurred in 1230. It had also attacked Florence in 1244, and the south of France and Spain in 1320 and 1333. This time, however, it would be different. This time the plague would not be confined to one or two towns, but would spread unpredictably and, at times it seemed, uncontrollably, across the whole continent, taking rich and poor to their graves in the worst single epidemic in history. But in October 1347, as the Messinese died screaming in their homes and in the streets from what seemed like a Divine punishment, the wider world must have been the last thing on their minds. The experience of the Black Death coming at midpoint in the 14th century changed the whole vision of life and art forever.

RECOMMENDED READING

Barbara Tuchman,

A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century,

Random House Trade Paperbacks; Reissue edition (July 12, 1987),

ISBN 0345349571

This is the best book in English on the 14th Century and I can't imagine anyone will ever write a better one. Barbara Tuchman was a miracle in the history world. She had no special training; she was just a Manhattan housewife who loved history. One day she walked down Fifth Avenue to the New York Public Library. She began to read and soon began to write and was soon into a spectacular career as an international best-selling author. She wrote five of the best books ever written in the field. Her masterpiece is A Distant Mirror on the 14th Century. She takes one character, Enguerand de Coucy, a French noble whose life touched almost everyone important in the century, and then she takes us all through the stories of the incredible century. History has never been better. It is like a novel; only better. You can read it on paper, in Kindle, or on audible.

Amazon Comment:

In this sweeping historical narrative, Barbara Tuchman writes of the cataclysmic 14th Century, when the energies of medieval Europe were devoted to fighting internecine wars and warding off the plague. Some medieval thinkers viewed these disasters as divine punishment for mortal wrongs; others, more practically, viewed them as opportunities to accumulate wealth and power. One of the latter, whose life informs much of Tuchman's book, was the French nobleman Enguerrand de Coucy, who enjoyed the opulence and elegance of the courtly tradition while ruthlessly exploiting the peasants under his thrall. Tuchman looks into such events as the Hundred Years War, the collapse of the medieval church, and the rise of various heresies, pogroms, and other events that caused medieval Europeans to wonder what they had done to deserve such horrors.

Reviews:

“Beautifully written, careful and thorough in its scholarship . . . What Ms. Tuchman does superbly is to tell how it was. . . . No one has ever done this better.”—The New York Review of Books

“A beautiful, extraordinary book . . . Tuchman at the top of her powers . . . She has done nothing finer.”—The Wall Street Journal

“Wise, witty, and wonderful . . . a great book, in a great historical tradition.”—Commentary

From the Publisher:

Anyone who has read The Guns of August or Stilwell and the American Experience in China, knows that Barbara Tuchman was one of the most gifted American writers of this century. Her subject was history, but her profiles of great men and great events are drawn with such power that reading Tuchman becomes a riveting experience. In A Distant Mirror, Barbara Tuchman illuminates the Dark Ages. Her description of medieval daily life, the role of the church, the influence of the Great Plagues, and the social and political conventions that make this period of history so engrossing, are carefully woven into an integrated narrative that sweeps the reader along. I am a particular devotee of medieval and pre-Renaissance music, so Barbara Tuchman's brilliant analysis of this period has special meaning for me—and I hope for many others. —George Davidson, Director of Production, The Ballantine Publishing Group

About the Author:

Barbara W. Tuchman (1912–1989) achieved prominence as a historian with The Zimmermann Telegram and international fame with The Guns of August—a huge bestseller and winner of the Pulitzer Prize. Her other works include Bible and Sword, The Proud Tower, Stilwell and the American Experience in China (for which Tuchman was awarded a second Pulitzer Prize), Notes from China, A Distant Mirror, Practicing History, The March of Folly, and The First Salute.

Week 15: Wed., Feb. 8, 2023

The Renaissance in Florence

Week 15

In 1390, Manuel Chrysoloras (1355-1415) came to Venice on a diplomatic errand as the representative of the Byzantine emperor in Constantinople. While visiting Venice he met a number of Florentines and one, Giacomo da Scarperia, followed him home to Constantinople to study Greek. Other Florentines heard about Chrysoloras and therefore in 1396, the Florentine Chancellor Coluccio Salutati invited Chrysoloras to come to Florence as a professor of Greek. Chrysoloras would teach the ancient language to whomever might want to attend the classes. This event—a formal program of Europeans studying Greek—is as useful a mark for the beginning of the Renaissance as any. With the arrival of Chrysoloras in Florence, almost a thousand years of Western European ignorance of Greek came to an end. And with this new field of study came new books, new publications, new ideas. The study of Greek sparked new interest in mathematics, astronomy, geography, geometry, optics, and cartography. By the 1420’s Florence found itself the center of an international movement that would help to create modern Europe.

RECOMMENDED READING

J. H. Plumb,

The Italian Renaissance,

Mariner Books; Revised edition (June 19, 2001),

ISBN 0618127380

Amazon: Spanning an age that witnessed great achievements in the arts and sciences, this definitive overview of the Italian Renaissance will both captivate ordinary readers and challenge specialists. Dr. Plumb’s impressive and provocative narrative is accompanied by contributions from leading historians, including Morris Bishop, J. Bronowski, Maria Bellonci, and many more, who have further illuminated the lives of some of the era’s most unforgettable personalities, from Petrarch to Pope Pius II, Michelangelo to Isabella d'Este, Machiavelli to Leonardo. A highly readable and engaging volume, THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE is a perfect introduction to the movement that shaped the Western world.

A useful book this week is the brilliant The Italian Renaissance by J. H. Plumb. This is a wonderful and succinct introduction to the Renaissance by one of our greatest historians, J. R. Plumb.

This is a wonderful book that is perfect for us as we spend a week talking about Brunelleschi and Renaissance Florence. I highly recommend it to you all. And now it is available in paperback ($13.00).

About the Author

Born and raised in Canada, Ross King has lived in England since 1992. In 2002―03, two books of his were published in the United States, Domino, about the world of masquerades and opera in 18th century London and the New York Times bestselling Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling. Nominated for a National Book Critics Circle Award in 2003 in the category of critisicm, in Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling King tells the story of the four years―1508-1512.―Michelangelo spent painting the ceiling of the newly restored Sistine chapel. In this extraordinary book, he presents a magnificent tapestry of day-to-day life of the ingenious Sistine scaffolding and outside in the upheaval of early 16th century Rome. King’s highly acclaimed Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture, was an instant hit in the U.S., landing on the New York Times, Boston Globe and San Francisco Chronicle bestseller lists and becoming a handselling favorite among booksellers. Brunelleschi’s Dome was chosen "The 2000 Book Sense Nonfiction Book of the Year" and a Book Sense 76 top ten selection. Anyone familiar with Ross King’s writing knows that he has an astonishing knowledge of European cultural history. He originally planned a career in academia, earning his Ph.D. in English Literature and moving to England to assume a research position at the University of London. King lives near Oxford, England, in the historic town of Woodstock, the site of Blenheim Palace. He is a devoted cyclist and hikes regularly in both the Pyrenees and the Canadian Rockies.

RECOMMENDED TEXTBOOK FOR THE YEAR

For the Renaissance in Florence see Honour, Chapter 10, beginning p. 416.

Week 16: Wed., Feb. 15, 2023

1500 in Milan

Week 16

In 1500, the world began to travel to Milan to see this incredible new painting that had been unveiled in 1498 and was already being called "the greatest painting in the world." Leonardo da Vinci from Tuscany was now world famous for the extraordinary fresco on the wall of the refectory of the convent church of Santa Maria Delle Grazie. At this moment three great painters were spreading the fame of Florence: Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael, all of whom were working together in the city by the Arno. The Last Supper by Leonardo in Milan is one of the world's most famous paintings, and one of the most studied and scrutinized. The painting represents the scene of the Last Supper of Jesus with his disciples, as it is told in the Gospel of John 13: 21. Leonardo specifically portrays the varying degree of anger and shock of each apostle when Jesus said one of them would betray him. The apostles have been identified from a manuscript by Leonardo found in the 19th Century (before then only Judas, Peter, John, and Jesus were positively identified). The Last Supper is not a true fresco: Because Leonardo sought greater detail and luminosity than could be achieved with traditional fresco (which cannot be modified as the artist works), he painted The Last Supper on a dry wall, then added an undercoat of white lead to enhance the brightness of the oil and tempera that was applied on top. These techniques were important for Leonardo's desire to work slowly on the painting, giving him sufficient time to develop the gradual shading or chiaroscuro that was essential to his style. Unfortunately though, due to Leonardo’s methods, the painting began deteriorating almost immediately. Environmental conditions and the ravages of wars have also threatened the painting. The most recent of numerous restorations was completed in 1999 after 21 years of painstaking labor.

RECOMMENDED READING

Walter Isaacson,

Leonardo da Vinci,

Simon & Schuster; 1st Edition (October 17, 2017),

ISBN 1501139150

Editorial Reviews:

"As always, [Isaacson] writes with a strongly synthesizing intelligence across a tremendous range; the result is a valuable introduction to a complex subject. . . . Beneath its diligent research, the book is a study in creativity: how to define it, how to achieve it. . . . Most important, Isaacson tells a powerful story of an exhilarating mind and life." —The New Yorker

“To read this magnificent biography of Leonardo da Vinci is to take a tour through the life and works of one of the most extraordinary human beings of all time and in the company of the most engaging, informed, and insightful guide imaginable. Walter Isaacson is at once a true scholar and a spellbinding writer. And what a wealth of lessons there are to be learned in these pages." —David McCullough, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Wright Brothers and 1776

“I’ve read a lot about Leonardo over the years, but I had never found one book that satisfactorily covered all the different facets of his life and work. Walter—a talented journalist and author I’ve gotten to know over the years—did a great job pulling it all together. . . . More than any other Leonardo book I’ve read, this one helps you see him as a complete human being and understand just how special he was.” —Bill Gates

For Leonardo in Milan, see Honour, pages 466-469.

Week 17: Wed., Feb. 22, 2023

1500 in Florence

Week 17

In the first decade of the 16th Century, Renaissance Florence reached a kind of peak of political creativity with their brilliant Secretary of State Niccolo Machiavelli, its wise leader Piero Soderini, and its youthful sculptor Michelangelo Buonarotti who was about to achieve international stardom with his new work David (1504). The more than 20 foot high David symbolized the courage of the little republic within the international big boys such as Milan and Naples. David stood up to the Goliaths of the world, and Florentines proudly displayed the new work when it was finished in 1504. the committee that decided where to put David include Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci. The civic pride, the artistic pride, that all of Florence felt when David was put on display, signals a kind of summit of Renaissance idealism. The Florence's Renaissance philosophers believed that Christian piety and Classical rationalism could be combined to create a new modern civic culture. Unfortunately, the city would soon learn that by the 1500's what mattered most was power -- brute military power. But for one shining moment, Florence enjoyed international respect for its government, its literature, and its art.

RECOMMENDED READING

For Michelangelo in Florence, see Hugh Honour, pages 474-483.

A NEW BIOGRAPHY OF MICHELANGELO

Antonio Forcellino,

Michaelangelo: A Tormented Life,

Polity; 1st Edition (October 10, 2011),

ISBN 0745640060

Week 18: Wed., Mar. 1, 2023

Raphael in Rome

Week 18

In the second decade of the 16th Century, the most celebrated and beloved painter in the capital of the Christian church was Raphael Sanzio from the small town of Urbino. Raphael had just spent a exciting period in Florence painting there at the same time as Leonardo and Michelangelo and now he was working for Pope Leo XIII, the Medici Pope Giovanni de' Medici. Pope Leo adored Raphael and gave him some of the greatest honors in the city. He showered rewards on the humble but very handsome young man. And all the city beat a pathway to his door, importuning him to paint a portrait or a mythological scene. Raphael was now finishing something he had begun in 1512 for the previous pope, Pope Julius II, Giovanni della Rovere. And as he labored on his painting of Greek philosophy in the papal apartments, Michelangelo worked next door on the Sistine ceiling. The fresco painting upon which Raphael was working would turn out to be his most famous creation and still is known now with the name the public attached to it when it was unveiled in 1512 -- The School of Athens.

RECOMMENDED READING

For Raphael in Rome, see Hugh Honour, pages 469-482. He discusses both Michelangelo and Raphael since they are both working for Pope Julius at the same time in the same building.

Week 19: Wed., Mar. 8, 2023

Giorgio Vasari and the New Fame of Artists

Week 19

Giorgio Vasari, born July 30, 1511 in Arezzo, was an Italian painter, architect, writer, and historian, best known for his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, considered the ideological foundation of art-historical writing. He was also the first to use the term "Renaissance" in print. He was born prematurely in Arezzo, Tuscany. Recommended at an early age by his cousin Luca Signorelli, he became a pupil of Guglielmo da Marsiglia, a skillful painter of stained glass. Sent to Florence at the age of sixteen by Cardinal Silvio Passerini, he joined the circle of Andrea del Sarto and his pupils Rosso Fiorentino and Jacopo Pontormo, where his humanist education was encouraged. He was befriended by Michelangelo, whose painting style would influence his own. He died on 27 June 1574 in Florence, Grand Duchy of Tuscany, aged 62. Vasari had immense influence on art and art history. His book with artist biographies came along at midcentury when the art of printing had advanced and when publishers could include woodcuts in the printed book-portraits of the various artists. Thus Vasari's book was the first to allow readers to have an impression of not only the stories of the artists, but also their appearance. The book had an incredible success. Edition after edition was printed. Overall, the Lives of the Artists changed the public's impression of art and artists forever. Before Vasari, artists had been thought of as glorified craftsmen. After Vasari, artists came to be seen in the public's eye as enabled, special, gifted. This impression was advanced above all due to the picture Vasari painted of his friend Michelangelo. Vasari turned Michelangelo into someone nearly divine. By 1600, thanks to Vasari artists were no longer just clever workers. Now they were special, unique, worthy of great rewards and lavish life styles.

See below the interior of one of the rooms of Vasari's beautiful villa in Arezzo.

RECOMMENDED READING

While this is just volume 1 of his series, if you want volume 2, it is available also.

Institute Library Call Number: 709.2 Vas LIV Bon

Two copies in our library (but not same edition as above).

Week 20: Wed., Mar. 15, 2023

Modernity

Week 20

In the late 1500's people began to use a new word -- modern. It appeared in all languages but the earliest were in Italian and English -- "moderno" and "modern." But soon all European languages produced their versions of this new word. The sudden success of the word around 1600 revealed that people all over Europe felt the need to distinguish their times with a new descriptive term. The word had first appeared in Italy back in the days of Francesco Petrarca and Boccacio. Both had used the word. But obviously, the Black Death threw off all language and all thinking so the word languished for a while. But in the early 1600's people felt they were living in new times -- times that needed a new word. And so was born "modern." By the third quarter of the 17th Century, a German historian writing a world history textbook for high school students produced a history in three volumes and called them Ancient, Medieval, and Modern. And so was born the tripartite description we all use every day. The Modern Age was born, and most saw its birthday as maybe January 1, 1600. The artist who most perfectly captured this birthday occasion was an Italian named Michelangelo da Merisi. He came from a small town outside of Milan, and when he was old enough he went to Milan to study art, then went off to Rome to seek fame and fortune. In Rome, he came to be known by the name of his natal hometown -- Caravaggio. The work of Caravaggio would explode onto the tired old art scene of Italy at the turn of the century. What he did was to clear away all the old cobwebs, the old traditions of what a painting should look like, the old ideas about proper subject matter and proper treatment of the subject matter. He was the walking embodiment of the word "modern." Now when we use that word, we mean modern in the way it was seeing 1600 not in the way it would be used 300 years later with Picasso and Matisse. They were part of "Modernism," i.e. the most modernist you could be. But certainly Caravaggio was modern and revolutionary in his times. But other people were modern too like Galileo and Newton and others who were writing the book on "modern." And other artists such as Vermeer and Velazquez were going to write their own versions of "modern." Below see an example of what paintings looked like before Caravaggio.

RECOMMENDED READING

Andrew Graham-Dixon,

Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane,

W. W. Norton & Company; 1 edition (November 12, 2012),

ISBN 9780393343434

Now look at what paintings looked like after Caravaggio showed everyone how to do it -- simple, clear, common people, common actions, simple clothes.