Week 21

Week 21: Wednesday, April 5, 2023

Baroque Rome

Week 21

In the early 17th Century Rome exploded with creative energy. The Roman church had recovered after the hours of the Protestant Reformation and a series of energetic constructive popes in the 1600's led the church to a new confidence and a new ideology. The capital of the international Roman Catholic Church benefited from this new age. The popes wanted their capital, their home to reflect this new age of Christian unity and therefore they launched one of the greatest ages of construction and artistic achievement for Rome since the great days of the Roman Empire. Bernini, Boromini, Caravaggio, Gentileschi, and on and on, all these great artists devoted their attention to works of art in Rome.

RECOMMENDED READING

Our Hugh Honour/John Fleming book continues to serve us all this quarter.

Pages 568-571, New Beginnings in Rome

Pages 578-583, The Easel Paintings in Italy, Bernini, Borromini

Howard Hibbard,

Bernini (Penguin Art and Architecture),

Penguin Books; Revised ed. Edition (January 18, 1991),

ISBN 0140135987

Bernini is the key figure in Baroque Rome. His creation of St. Peter's Basilica piazza is the quintessence of the Baroque.

22

Week 22: Wednesday, April 12, 2023

The Spaniards

Week 22

Roman Catholic 17th Century Spain was in close communication with Rome, and therefore Spanish artists picked up on the artistic revolution going on in Rome before anyone else. Spaniards went to Rome to study Caravaggio and brought back all his stylistic advances and some like Jose Ribera stayed in Italy for the rest of their careers. Caravaggio became one of the most widely imitated artists in the history of western art. After his untimely death in 1610, many Italian and non-Italian artists alike came to be considered his “followers,” even though they had never met the artist or worked alongside him. The most sensitive to Caravaggio was Velazquez who went twice and completely changed his style once he had absorbed Caravaggio in Rome. But other Spanish artists also continued the Caravaggio style (they were called "Caravaggisti") and Zurburan was called "The Spanish Caravaggio."

Spanish Artists in the 17th Century:

Diego Velázquez, 1599-1660

Francisco de Zurbarán, 1598-1664

Jusepe de Ribera (José de Ribera), 1591-1652

Antonio de Pereda, 1611-1678

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, 1617-1682

The magnificent still-life below by Francisco de Zurbarán is Still Life with Lemons,Oranges and a Rose. It is one of the greatest paintings to come out of 17th Century Spain. And fortunately for all of us we can get in a car and drive to LA and see it at the Norton Simon Museum. Zurbarán absorbed the magic of Caravaggio and then he blended it with the Spanish life and death themes to create something wholly Spanish and spectacularly beautiful. The poster for this has been one of the best-selling posters at the Norton Simon for years. Norman Bryson writes: "Lemons, Oranges, and a Rose shows a visual field so purified and so perfectly composed that the familiar objects seem on the brink of transfiguration or (the inevitable word) transubstantiation. Standing at some imminent intersection with the divine, and with eternity, they exactly break with the normally human."

RECOMMENDED READING

Our Hugh Honour/John Fleming book continues to serve us all this quarter.

Pages 588-591, Velázquez

Antonio Dominguez Ortiz,

Velazquez,

Harry N Abrams Inc; 1st Edition (January 1, 1990),

ISBN 0810939061

Editorial Reviews:

This sumptuous book is the catalog for the once-in-a-lifetime U.S. exhibition of the 17th Century Spanish artist frequently called the greatest painter of all time. The gorgeous reproductions illustrate every painting in the exhibition, and the many close-up details reveal the fabulous brushwork that makes Velazquez truly a painter's painter. The introductory essays provide a foundation in the history of Spain during Velazquez's life and a biography of the artist combined with an overview of his art. Catalog entries thoroughly describe each painting in terms of subject matter, style, and provenance, as well as any scholarly differences of opinion regarding dating or authenticity. This is a major publication documenting an important exhibition and should be acquired by all libraries for their patrons who love painting at its best. --from Library Journal

Amazon Customer Review:

Trond Sigurdsen

5.0 out of 5 stars, Best book on Velazquez

Reviewed in the United States on August 3, 2007

I have several books on this supremely talented Spanish painter, and I have to say that this work is still the best on the subject. First, the text is very informative as to the life and times of Velazquez. Furthermore, the information on each painting is well written, and does not feel repetitive. However, the most important aspect of the book is the reproductions, which are (with one or two exceptions) the best you will find anywhere even today, seventeen years after the book was published!

23

Week 23: Wednesday, April 19, 2023

The Dutch Golden Age

Week 23

Over the course of the 17th Century, the Dutch nation became one of the wealthiest and most powerful in the world, employing its naval prowess to dominate international trade and create a vast colonial empire. But this period began in turmoil. The 1568 revolt of the Seventeen Provinces (modern-day Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and sections of northern France and western Germany) against Philip II of Spain, the sovereign of the Habsburg Netherlands, led to the Eighty Years’ War, or Dutch War of Independence. Under William of Orange, the northern provinces overthrew the Habsburg armies and established the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands(The Dutch Republic), which in 1648 was recognized as an independent country. The Southern Netherlands remained under Catholic Spain’s control (today's Belgium), prompting countless Flemish craftsmen to flee north, where their innovative techniques and pioneering subjects were disseminated throughout the Republic. The newfound prosperity in the 17th Century engendered great advancements in the arts and sciences. With surplus income, Dutch citizens enthusiastically purchased paintings and works of decorative art. What followed was an enormous surge in art production in an unprecedented variety of types and levels of quality. (The foregoing is from the catalog of one of the greatest art shows in the USA called "The Dutch Golden Age" at The Frick in New York City.

RECOMMENDED READING

Our Hugh Honour/John Fleming book continues to serve us all this quarter.

Pages 591-603, Dutch Painting

24

Week 24: Wednesday, April 26, 2023

Classicism

Week 24

During the 17th and 18th Centuries, Europe was swept by a rage for the Classical—classical temples, classical salt and pepper, classical clothes—anything that hinted of ancient Rome. It was more about Rome than Greece because the monarchs liked the idea of Roman emperors. Many wanted to be "emperors." And none wanted this more than did King Louis XIV of France. Louis had one of the longest reigns in history—72 years (from 1643 to 1715). And in that long reign Louis managed to grab almost all the power in France into his own hands. There were no representative assemblies, little power in the councils, little power even in the towns and cities. Everything revolved around the Sun King as does the universe revolve around the sun. (Yes, this was a Copernican universe.) And with all this power, there was no better art style for him than the style of the Roman emperors. And so voila!—Versailles. The great palatial complex that Louis built outside of Paris summed up every single classical architectural theme available. But it wasn't only Louis and the French aristocracy that embraced Classicism. Germany loved it. England loved it. Spain loved it. And it wasn't only in architecture that the mania for the classical style was evident. It was also a new subject in the universities, among the intellectuals, in new published books. Among the stars of this whole new field of study was Johann Joachim Winkelmann (1717–1768), a German art historian and archaeologist. He was a pioneering Hellenist who first articulated the difference between Greek, Greco-Roman and Roman art. "The prophet and founding hero of modern archaeology," Winckelmann was one of the founders of scientific archaeology and first applied the categories of style on a large, systematic basis to the history of art. Many consider him the father of the discipline of art history. He was one of the first to separate Greek Art into periods and time classifications. His would be the decisive influence on the rise of the Neoclassical movement during the late 18th Century. His writings influenced not only a new science of archaeology and art history but Western painting, sculpture, literature, and even philosophy. Winckelmann's History of Ancient Art (1764) was one of the first books written in German to become a classic of European literature. His subsequent influence on Lessing, Herder, Goethe, Hölderlin, Heine, Nietzsche, George, and Spengler has been provocatively called The Tyranny of Greece over Germany. Today Humboldt University of Berlin's Winckelmann Institute is dedicated to the study of classical archaeology. Winckelmann was homosexual, and open homoeroticism formed his writings on aesthetics. This was recognized by his contemporaries such as Goethe.

RECOMMENDED READING

Pages 585-588, Poussin and Claude

Pages 603-606, England and France

Pages 627-633, Neoclassicism, or the "True Style"

As you can see, our art historian Hugh Honour is also the author of the best book on Neoclassicism in English. "Neoclassicism" is the word we use to indicate all the later appearances of Classicism in architecture, etc., and Classicism is essentially Greek in origin with some important additions from Rome.

25

Week 25: Wednesday, May 3, 2023

The Art of the English Aristocracy

Week 25

During the 18th Century, England became the richest nation with the great empire in the world. Suddenly the ruling class of the emerald isle had piles of money to spend, and spend it they did on country houses filled with art, sculpture, paintings, prints of Roman ruins, coins, statues of Roman orators, statues of Roman athletes, statues of Roman emperor and more. They carried off everything they could buy. Their classical homes were often spectacular museums filled with extremely valuable art. And then they commissioned paintings, especially portraits of their families, their wives, their children, their mistresses (disguised as some Greek goddess). The painters they loved were above all Gainsborough and Reynolds, but there were many others. George Romney was one of the greatest. See his fabulous Miss Willoughby in the National Gallery in Washington, DC below.

RECOMMENDED READING

Pages 622-627, English Sense and Sensibility

26

Week 26: Wednesday, May 10, 2023

Delacroix and Romanticism

Week 26

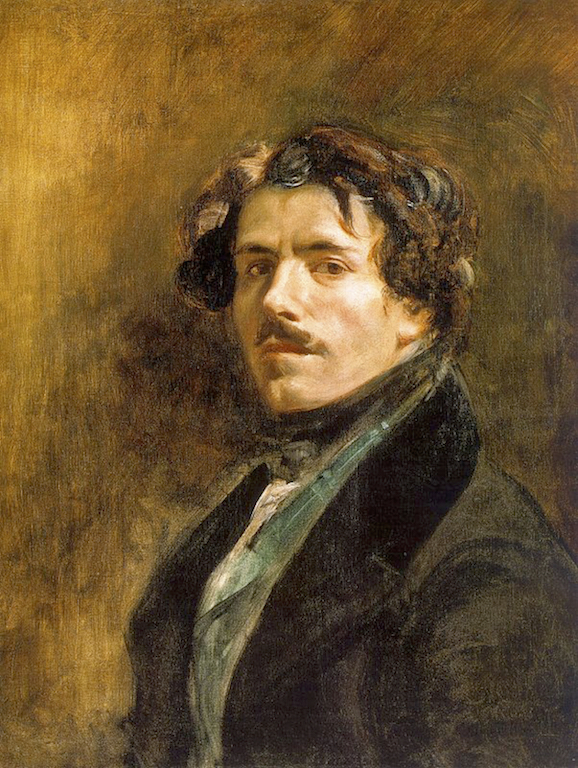

Romanticism was a movement that began in the mid 18th Century in the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau in Paris. It spread rapidly all over Europe to Germany, England, and Italy. It began to appear in painting in the early 19th Century above all in the work of the young Eugène Delacroix. Eugène Delacroix was born on 26 April 1798, at Charenton-Saint-Maurice in Île-de-France, near Paris. His mother was Victoire Oeben, the daughter of the cabinet-maker Jean-François Oeben. He had three much older siblings. Charles-Henri Delacroix (1779–1845) rose to the rank of general in the Napoleonic army. Henriette (1780–1827) married the diplomat Raymond de Verninac Saint-Maur (1762–1822). Henri was born six years later. He was killed at the Battle of Friedland on 14 June 1807. There are medical reasons to believe that Eugène's legitimate father, Charles-François Delacroix, was not able to procreate at the time of Eugène's conception. Talleyrand, who was a friend of the family and successor of Charles Delacroix as Minister of Foreign Affairs, and whom the adult Eugène much resembled in appearance and character, considered himself as his real father. After assuming his office as foreign minister, Talleyrand dispatched Delacroix to The Hague in the capacity of French ambassador to the then Batavian Republic. Delacroix who at the time suffered from erectile dysfunction returned to Paris in early September 1797, only to find his wife pregnant. Talleyrand went on to assist Eugène in the form of numerous anonymous commissions. Throughout his career as a painter, he was protected by Talleyrand, who served successively the Restoration Bourbon government after Napoleon and King Louis-Philippe n the 1830's, and ultimately as ambassador of France in Great Britain, and later by Talleyrand's grandson, Charles Auguste Louis Joseph, duc de Morny, half-brother of Napoleon III and speaker of the French House of Commons. His legitimate father, Charles Delacroix, died in 1805, and his mother in 1814, leaving 16-year-old Eugène an orphan. Although the young Delacroix had emerged out of the highest circles of power in France, his personal nature and career directions turned him into a rebel—a Romantic rebel. He reveled against the perfectionism of the Neo-classical style that then dominated French art. Delacroix fearlessly attacked this stodgy old style with a new technique and new subjects. He moved away from all the Classical myths and instead wandered in North Africa where he found exciting subjects, colors, and stories. In the process he almost singlehandedly created a whole new artistic style. When he died in 1863, all his artistic children—Renoir, Monet, Degas, Cezanne, Pissarro, Morisot, Manet, Bazille, gathered at a massive Paris retrospective show that became legendary in the history of art.

RECOMMENDED READING

Pages 640-659, Romanticism, Romanticism and Philosophy, Romantic Landscape Painting

27

Week 27: Wednesday, May 17, 2023

Art Wars in Paris

Week 27

From 1850 to about 1900, Paris became the center of art in the whole world. By the end of the century, thousands of wealthy buyers were traveling across the world to come to Paris and buy paintings. Never in history have so many people cared so much about so many artists and their works. Americans such as Isabella Stewart Gardner crossed the Atlantic every year to see the latest world of art in Paris. Young men and women risked all they had on a trip to Paris in the hope that they might get into one of the art studios and be able to begin their careers as painters. Three of the greatest American artists ever—sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, painters Mary Cassatt and John Singer Sargent—flourished in Paris, inspired by French masters. In the middle of all this enthusiasm about art, there was a cultural war being fought. The traditionalists, the Neoclassicists such as the grand master Ingres fought to maintain his idea of correct art training: years of drawing first, drawing from models, years of study of the history of art, years of preparation and then finally real oil painting in the studio. Maybe the young painter's first painting would beef a Greek myth like Venus and Adonis. The rebel, Eugene Delacroix threw off all this painful training, all this waiting, and took his students outside to paint color and excitement—contemporary stories, scandals, exotic places. All during this half-century the war went on. Then in 1900, the old guard collapsed. The two greatest successes of the Classical tradition, Jean-Léon Gérôme and William-Adolphe Bouguereau died within one year of each other. The great salons ceased to take place. It was over. The rebels won.

RECOMMENDED READING

Pages 701-715, Impressionism, Japonisme

28

Week 28: Wednesday, May 24, 2023

The Radicals

Week 28

The war between the traditionalists and the rebels went on all through the 19th Century. In the 1860's there emerged a group of young men and women who had a cohesive plan for a new art. By 1874 they were ready to show the world their work, and they did so in April 1874 on the big Boulevard des Capucines in the renewed Paris with great wide boulevards, new sidewalk cafes, new bookstalls everywhere, and charming street stalls selling art reproductions now available in color for the first time in history. This new group came to be know as the Impressionists, although none of them liked the name since it implied their paintings were mere "impressions." But impressions were exactly what a public wanted. Not at first. It took some years, tough years of failure and poverty. But around 1880 with Renoir's sale of his magnificent portrait of Madame Georges Charpentier and her children for a very big price, things changed. Later one of the smart art dealers of Paris took a load of Impressionist paintings to New York and staged a show with phenomenal results. At that moment the international world of art changed. The rebels were now the victors. But there was still another group in Paris. They were just a bit younger than the Impressionists born about 1840. This group were born on or around 1850. And this younger group went beyond the Impressionists. They left behind the look of the real world and elaborated and abstracted and distorted for an emotional effect. Their work was attacked and scorned at first when they showed their works in the 1890's. The group included Emile Bernard, Paul Gauguin, Paul Cezanne, Vincent Van Gogh, and Georges-Pierre Seurat. Their innovations were going to inspire the two real radicals -- Picasso and Matisse in the 1900's.

RECOMMENDED READING

Pages 715-722 Symbolism

Pages 729-733, Cezanne

29

Week 29: Wednesday, May 31, 2023

The Modernists

Week 29

Here is a nice general introduction from the Wikipedia article on Modernism:

"Modernism is both a philosophical movement and an art movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, and social organization which reflected the newly emerging industrial world, including features such as urbanization, new technologies, and war. Artists attempted to depart from traditional forms of art, which they considered outdated or obsolete. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 injunction to "Make it new!" was the touchstone of the movement's approach. Modernist innovations included abstract art, the stream-of-consciousness novel, montage cinema, atonal and twelve-tone music, and divisionist painting. Modernism explicitly rejected the ideology of realism and made use of the works of the past by the employment of reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision, and parody. Modernism also rejected the certainty of Enlightenment thinking that accents the rational structure of the universe and of knowledge, and many modernists also rejected religious belief. A notable characteristic of modernism is self-consciousness concerning artistic and social traditions, which often led to experimentation with form, along with the use of techniques that drew attention to the processes and materials used in creating works of art."

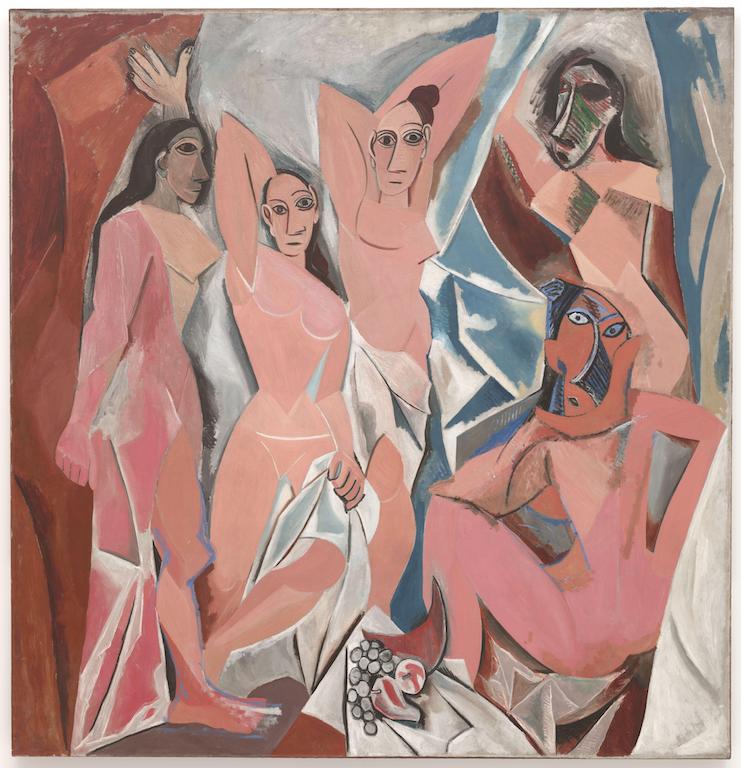

All of the above is true. It now has a name that we use freely -- Modernism, but that is all a product of our ability to look back a hundred years to 1900 and the origins of the Modernists. People certainly knew that something amazing was happening in the arts in 1905 with some of the most radical innovations by both Picasso and Matisse. But no one called them Modernists. They were wild beasts or something like that. For our study of the visual arts, it is Picasso and Matisse who matter. They meet at Gertrude Stein's Paris apartment. You can see all of this in the wonderful Woody Allen movie Midnight in Paris where he recreates perfectly that world of Stein with Picasso and Matisse and Modigliani and Alice B. Toklas and Hemingway all there. One can say that in this apartment is born Modernism. Stein herself was a mother of Modernism. The painting below by Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon is the declaration of independence of the movement. It is now to be seen in the Museum of Modern Art, New York City.

RECOMMENDED READING:

Pages 768-797, Art from 1900 to 1919

A good gossipy read with great stories:

Sue Roe,

In Montmartre: Picasso, Matisse and the Birth of Modernist Art,

Penguin Press,

ISBN 1594204950

Institute Library Call Number: 709.04 Roe MONT

The updated 2004 edition in quality soft cover; used copies available:

Robert Hughes,

The Shock of the New: Art and the Century of Change,

Thames & Hudson,

ISBN 0500275823

30

Week 30: Wednesday, June 7, 2023

The Twentieth Century

Week 30

20th Century art began with Modernism in the late 19th Century. Movements of Post-Impressionism (Les Nabis), Art Nouveau, and Symbolism from the 19th Century led to the first 20th Century art movements of Fauvism in France and Die Brücke ("The Bridge") in Germany. Fauvism in Paris introduced heightened non-representational colour into figurative painting. Die Brücke strove for emotional Expressionism. Another German group was Der Blaue Reiter ("The Blue Rider"), led by Kandinsky in Munich, who associated the blue rider image with a spiritual non-figurative mystical art of the future. Kandinsky, Kupka, R. Delaunay and Picabia were pioneers of abstract (or non-representational) art. Cubism, generated by Picasso, Braque, Metzinger, Gleizes, and others rejected the plastic norms of the Renaissance by introducing multiple perspectives into a two-dimensional image. Futurism incorporated the depiction of movement and machine age imagery. Dadaism's most notable exponents included Marcel Duchamp, who rejected conventional art styles altogether by exhibiting found objects (notably a urinal), and Francis Picabia with his Portraits Mécaniques.

RECOMMENDED READING:

The updated 2004 edition in quality soft cover; used copies available:

Robert Hughes,

The Shock of the New: Art and the Century of Change,

Thames & Hudson,

ISBN 0500275823

All

Week 21: Wed., Apr. 5, 2023

Baroque Rome

Week 21

In the early 17th Century Rome exploded with creative energy. The Roman church had recovered after the hours of the Protestant Reformation and a series of energetic constructive popes in the 1600's led the church to a new confidence and a new ideology. The capital of the international Roman Catholic Church benefited from this new age. The popes wanted their capital, their home to reflect this new age of Christian unity and therefore they launched one of the greatest ages of construction and artistic achievement for Rome since the great days of the Roman Empire. Bernini, Boromini, Caravaggio, Gentileschi, and on and on, all these great artists devoted their attention to works of art in Rome.

RECOMMENDED READING

Our Hugh Honour/John Fleming book continues to serve us all this quarter.

Pages 568-571, New Beginnings in Rome

Pages 578-583, The Easel Paintings in Italy, Bernini, Borromini

Howard Hibbard,

Bernini (Penguin Art and Architecture),

Penguin Books; Revised ed. Edition (January 18, 1991),

ISBN 0140135987

Bernini is the key figure in Baroque Rome. His creation of St. Peter's Basilica piazza is the quintessence of the Baroque.

Week 22: Wed., Apr. 12, 2023

The Spaniards

Week 22

Roman Catholic 17th Century Spain was in close communication with Rome, and therefore Spanish artists picked up on the artistic revolution going on in Rome before anyone else. Spaniards went to Rome to study Caravaggio and brought back all his stylistic advances and some like Jose Ribera stayed in Italy for the rest of their careers. Caravaggio became one of the most widely imitated artists in the history of western art. After his untimely death in 1610, many Italian and non-Italian artists alike came to be considered his “followers,” even though they had never met the artist or worked alongside him. The most sensitive to Caravaggio was Velazquez who went twice and completely changed his style once he had absorbed Caravaggio in Rome. But other Spanish artists also continued the Caravaggio style (they were called "Caravaggisti") and Zurburan was called "The Spanish Caravaggio."

Spanish Artists in the 17th Century:

Diego Velázquez, 1599-1660

Francisco de Zurbarán, 1598-1664

Jusepe de Ribera (José de Ribera), 1591-1652

Antonio de Pereda, 1611-1678

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, 1617-1682

The magnificent still-life below by Francisco de Zurbarán is Still Life with Lemons,Oranges and a Rose. It is one of the greatest paintings to come out of 17th Century Spain. And fortunately for all of us we can get in a car and drive to LA and see it at the Norton Simon Museum. Zurbarán absorbed the magic of Caravaggio and then he blended it with the Spanish life and death themes to create something wholly Spanish and spectacularly beautiful. The poster for this has been one of the best-selling posters at the Norton Simon for years. Norman Bryson writes: "Lemons, Oranges, and a Rose shows a visual field so purified and so perfectly composed that the familiar objects seem on the brink of transfiguration or (the inevitable word) transubstantiation. Standing at some imminent intersection with the divine, and with eternity, they exactly break with the normally human."

RECOMMENDED READING

Our Hugh Honour/John Fleming book continues to serve us all this quarter.

Pages 588-591, Velázquez

Antonio Dominguez Ortiz,

Velazquez,

Harry N Abrams Inc; 1st Edition (January 1, 1990),

ISBN 0810939061

Editorial Reviews:

This sumptuous book is the catalog for the once-in-a-lifetime U.S. exhibition of the 17th Century Spanish artist frequently called the greatest painter of all time. The gorgeous reproductions illustrate every painting in the exhibition, and the many close-up details reveal the fabulous brushwork that makes Velazquez truly a painter's painter. The introductory essays provide a foundation in the history of Spain during Velazquez's life and a biography of the artist combined with an overview of his art. Catalog entries thoroughly describe each painting in terms of subject matter, style, and provenance, as well as any scholarly differences of opinion regarding dating or authenticity. This is a major publication documenting an important exhibition and should be acquired by all libraries for their patrons who love painting at its best. --from Library Journal

Amazon Customer Review:

Trond Sigurdsen

5.0 out of 5 stars, Best book on Velazquez

Reviewed in the United States on August 3, 2007

I have several books on this supremely talented Spanish painter, and I have to say that this work is still the best on the subject. First, the text is very informative as to the life and times of Velazquez. Furthermore, the information on each painting is well written, and does not feel repetitive. However, the most important aspect of the book is the reproductions, which are (with one or two exceptions) the best you will find anywhere even today, seventeen years after the book was published!

Week 23: Wed., Apr. 19, 2023

The Dutch Golden Age

Week 23

Over the course of the 17th Century, the Dutch nation became one of the wealthiest and most powerful in the world, employing its naval prowess to dominate international trade and create a vast colonial empire. But this period began in turmoil. The 1568 revolt of the Seventeen Provinces (modern-day Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and sections of northern France and western Germany) against Philip II of Spain, the sovereign of the Habsburg Netherlands, led to the Eighty Years’ War, or Dutch War of Independence. Under William of Orange, the northern provinces overthrew the Habsburg armies and established the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands(The Dutch Republic), which in 1648 was recognized as an independent country. The Southern Netherlands remained under Catholic Spain’s control (today's Belgium), prompting countless Flemish craftsmen to flee north, where their innovative techniques and pioneering subjects were disseminated throughout the Republic. The newfound prosperity in the 17th Century engendered great advancements in the arts and sciences. With surplus income, Dutch citizens enthusiastically purchased paintings and works of decorative art. What followed was an enormous surge in art production in an unprecedented variety of types and levels of quality. (The foregoing is from the catalog of one of the greatest art shows in the USA called "The Dutch Golden Age" at The Frick in New York City.

RECOMMENDED READING

Our Hugh Honour/John Fleming book continues to serve us all this quarter.

Pages 591-603, Dutch Painting

Week 24: Wed., Apr. 26, 2023

Classicism

Week 24

During the 17th and 18th Centuries, Europe was swept by a rage for the Classical—classical temples, classical salt and pepper, classical clothes—anything that hinted of ancient Rome. It was more about Rome than Greece because the monarchs liked the idea of Roman emperors. Many wanted to be "emperors." And none wanted this more than did King Louis XIV of France. Louis had one of the longest reigns in history—72 years (from 1643 to 1715). And in that long reign Louis managed to grab almost all the power in France into his own hands. There were no representative assemblies, little power in the councils, little power even in the towns and cities. Everything revolved around the Sun King as does the universe revolve around the sun. (Yes, this was a Copernican universe.) And with all this power, there was no better art style for him than the style of the Roman emperors. And so voila!—Versailles. The great palatial complex that Louis built outside of Paris summed up every single classical architectural theme available. But it wasn't only Louis and the French aristocracy that embraced Classicism. Germany loved it. England loved it. Spain loved it. And it wasn't only in architecture that the mania for the classical style was evident. It was also a new subject in the universities, among the intellectuals, in new published books. Among the stars of this whole new field of study was Johann Joachim Winkelmann (1717–1768), a German art historian and archaeologist. He was a pioneering Hellenist who first articulated the difference between Greek, Greco-Roman and Roman art. "The prophet and founding hero of modern archaeology," Winckelmann was one of the founders of scientific archaeology and first applied the categories of style on a large, systematic basis to the history of art. Many consider him the father of the discipline of art history. He was one of the first to separate Greek Art into periods and time classifications. His would be the decisive influence on the rise of the Neoclassical movement during the late 18th Century. His writings influenced not only a new science of archaeology and art history but Western painting, sculpture, literature, and even philosophy. Winckelmann's History of Ancient Art (1764) was one of the first books written in German to become a classic of European literature. His subsequent influence on Lessing, Herder, Goethe, Hölderlin, Heine, Nietzsche, George, and Spengler has been provocatively called The Tyranny of Greece over Germany. Today Humboldt University of Berlin's Winckelmann Institute is dedicated to the study of classical archaeology. Winckelmann was homosexual, and open homoeroticism formed his writings on aesthetics. This was recognized by his contemporaries such as Goethe.

RECOMMENDED READING

Pages 585-588, Poussin and Claude

Pages 603-606, England and France

Pages 627-633, Neoclassicism, or the "True Style"

As you can see, our art historian Hugh Honour is also the author of the best book on Neoclassicism in English. "Neoclassicism" is the word we use to indicate all the later appearances of Classicism in architecture, etc., and Classicism is essentially Greek in origin with some important additions from Rome.

Week 25: Wed., May. 3, 2023

The Art of the English Aristocracy

Week 25

During the 18th Century, England became the richest nation with the great empire in the world. Suddenly the ruling class of the emerald isle had piles of money to spend, and spend it they did on country houses filled with art, sculpture, paintings, prints of Roman ruins, coins, statues of Roman orators, statues of Roman athletes, statues of Roman emperor and more. They carried off everything they could buy. Their classical homes were often spectacular museums filled with extremely valuable art. And then they commissioned paintings, especially portraits of their families, their wives, their children, their mistresses (disguised as some Greek goddess). The painters they loved were above all Gainsborough and Reynolds, but there were many others. George Romney was one of the greatest. See his fabulous Miss Willoughby in the National Gallery in Washington, DC below.

RECOMMENDED READING

Pages 622-627, English Sense and Sensibility

Week 26: Wed., May. 10, 2023

Delacroix and Romanticism

Week 26

Romanticism was a movement that began in the mid 18th Century in the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau in Paris. It spread rapidly all over Europe to Germany, England, and Italy. It began to appear in painting in the early 19th Century above all in the work of the young Eugène Delacroix. Eugène Delacroix was born on 26 April 1798, at Charenton-Saint-Maurice in Île-de-France, near Paris. His mother was Victoire Oeben, the daughter of the cabinet-maker Jean-François Oeben. He had three much older siblings. Charles-Henri Delacroix (1779–1845) rose to the rank of general in the Napoleonic army. Henriette (1780–1827) married the diplomat Raymond de Verninac Saint-Maur (1762–1822). Henri was born six years later. He was killed at the Battle of Friedland on 14 June 1807. There are medical reasons to believe that Eugène's legitimate father, Charles-François Delacroix, was not able to procreate at the time of Eugène's conception. Talleyrand, who was a friend of the family and successor of Charles Delacroix as Minister of Foreign Affairs, and whom the adult Eugène much resembled in appearance and character, considered himself as his real father. After assuming his office as foreign minister, Talleyrand dispatched Delacroix to The Hague in the capacity of French ambassador to the then Batavian Republic. Delacroix who at the time suffered from erectile dysfunction returned to Paris in early September 1797, only to find his wife pregnant. Talleyrand went on to assist Eugène in the form of numerous anonymous commissions. Throughout his career as a painter, he was protected by Talleyrand, who served successively the Restoration Bourbon government after Napoleon and King Louis-Philippe n the 1830's, and ultimately as ambassador of France in Great Britain, and later by Talleyrand's grandson, Charles Auguste Louis Joseph, duc de Morny, half-brother of Napoleon III and speaker of the French House of Commons. His legitimate father, Charles Delacroix, died in 1805, and his mother in 1814, leaving 16-year-old Eugène an orphan. Although the young Delacroix had emerged out of the highest circles of power in France, his personal nature and career directions turned him into a rebel—a Romantic rebel. He reveled against the perfectionism of the Neo-classical style that then dominated French art. Delacroix fearlessly attacked this stodgy old style with a new technique and new subjects. He moved away from all the Classical myths and instead wandered in North Africa where he found exciting subjects, colors, and stories. In the process he almost singlehandedly created a whole new artistic style. When he died in 1863, all his artistic children—Renoir, Monet, Degas, Cezanne, Pissarro, Morisot, Manet, Bazille, gathered at a massive Paris retrospective show that became legendary in the history of art.

RECOMMENDED READING

Pages 640-659, Romanticism, Romanticism and Philosophy, Romantic Landscape Painting

Week 27: Wed., May. 17, 2023

Art Wars in Paris

Week 27

From 1850 to about 1900, Paris became the center of art in the whole world. By the end of the century, thousands of wealthy buyers were traveling across the world to come to Paris and buy paintings. Never in history have so many people cared so much about so many artists and their works. Americans such as Isabella Stewart Gardner crossed the Atlantic every year to see the latest world of art in Paris. Young men and women risked all they had on a trip to Paris in the hope that they might get into one of the art studios and be able to begin their careers as painters. Three of the greatest American artists ever—sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, painters Mary Cassatt and John Singer Sargent—flourished in Paris, inspired by French masters. In the middle of all this enthusiasm about art, there was a cultural war being fought. The traditionalists, the Neoclassicists such as the grand master Ingres fought to maintain his idea of correct art training: years of drawing first, drawing from models, years of study of the history of art, years of preparation and then finally real oil painting in the studio. Maybe the young painter's first painting would beef a Greek myth like Venus and Adonis. The rebel, Eugene Delacroix threw off all this painful training, all this waiting, and took his students outside to paint color and excitement—contemporary stories, scandals, exotic places. All during this half-century the war went on. Then in 1900, the old guard collapsed. The two greatest successes of the Classical tradition, Jean-Léon Gérôme and William-Adolphe Bouguereau died within one year of each other. The great salons ceased to take place. It was over. The rebels won.

RECOMMENDED READING

Pages 701-715, Impressionism, Japonisme

Week 28: Wed., May. 24, 2023

The Radicals

Week 28

The war between the traditionalists and the rebels went on all through the 19th Century. In the 1860's there emerged a group of young men and women who had a cohesive plan for a new art. By 1874 they were ready to show the world their work, and they did so in April 1874 on the big Boulevard des Capucines in the renewed Paris with great wide boulevards, new sidewalk cafes, new bookstalls everywhere, and charming street stalls selling art reproductions now available in color for the first time in history. This new group came to be know as the Impressionists, although none of them liked the name since it implied their paintings were mere "impressions." But impressions were exactly what a public wanted. Not at first. It took some years, tough years of failure and poverty. But around 1880 with Renoir's sale of his magnificent portrait of Madame Georges Charpentier and her children for a very big price, things changed. Later one of the smart art dealers of Paris took a load of Impressionist paintings to New York and staged a show with phenomenal results. At that moment the international world of art changed. The rebels were now the victors. But there was still another group in Paris. They were just a bit younger than the Impressionists born about 1840. This group were born on or around 1850. And this younger group went beyond the Impressionists. They left behind the look of the real world and elaborated and abstracted and distorted for an emotional effect. Their work was attacked and scorned at first when they showed their works in the 1890's. The group included Emile Bernard, Paul Gauguin, Paul Cezanne, Vincent Van Gogh, and Georges-Pierre Seurat. Their innovations were going to inspire the two real radicals -- Picasso and Matisse in the 1900's.

RECOMMENDED READING

Pages 715-722 Symbolism

Pages 729-733, Cezanne

Week 29: Wed., May. 31, 2023

The Modernists

Week 29

Here is a nice general introduction from the Wikipedia article on Modernism:

"Modernism is both a philosophical movement and an art movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, and social organization which reflected the newly emerging industrial world, including features such as urbanization, new technologies, and war. Artists attempted to depart from traditional forms of art, which they considered outdated or obsolete. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 injunction to "Make it new!" was the touchstone of the movement's approach. Modernist innovations included abstract art, the stream-of-consciousness novel, montage cinema, atonal and twelve-tone music, and divisionist painting. Modernism explicitly rejected the ideology of realism and made use of the works of the past by the employment of reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision, and parody. Modernism also rejected the certainty of Enlightenment thinking that accents the rational structure of the universe and of knowledge, and many modernists also rejected religious belief. A notable characteristic of modernism is self-consciousness concerning artistic and social traditions, which often led to experimentation with form, along with the use of techniques that drew attention to the processes and materials used in creating works of art."

All of the above is true. It now has a name that we use freely -- Modernism, but that is all a product of our ability to look back a hundred years to 1900 and the origins of the Modernists. People certainly knew that something amazing was happening in the arts in 1905 with some of the most radical innovations by both Picasso and Matisse. But no one called them Modernists. They were wild beasts or something like that. For our study of the visual arts, it is Picasso and Matisse who matter. They meet at Gertrude Stein's Paris apartment. You can see all of this in the wonderful Woody Allen movie Midnight in Paris where he recreates perfectly that world of Stein with Picasso and Matisse and Modigliani and Alice B. Toklas and Hemingway all there. One can say that in this apartment is born Modernism. Stein herself was a mother of Modernism. The painting below by Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon is the declaration of independence of the movement. It is now to be seen in the Museum of Modern Art, New York City.

RECOMMENDED READING:

Pages 768-797, Art from 1900 to 1919

A good gossipy read with great stories:

Sue Roe,

In Montmartre: Picasso, Matisse and the Birth of Modernist Art,

Penguin Press,

ISBN 1594204950

Institute Library Call Number: 709.04 Roe MONT

The updated 2004 edition in quality soft cover; used copies available:

Robert Hughes,

The Shock of the New: Art and the Century of Change,

Thames & Hudson,

ISBN 0500275823

Week 30: Wed., Jun. 7, 2023

The Twentieth Century

Week 30

20th Century art began with Modernism in the late 19th Century. Movements of Post-Impressionism (Les Nabis), Art Nouveau, and Symbolism from the 19th Century led to the first 20th Century art movements of Fauvism in France and Die Brücke ("The Bridge") in Germany. Fauvism in Paris introduced heightened non-representational colour into figurative painting. Die Brücke strove for emotional Expressionism. Another German group was Der Blaue Reiter ("The Blue Rider"), led by Kandinsky in Munich, who associated the blue rider image with a spiritual non-figurative mystical art of the future. Kandinsky, Kupka, R. Delaunay and Picabia were pioneers of abstract (or non-representational) art. Cubism, generated by Picasso, Braque, Metzinger, Gleizes, and others rejected the plastic norms of the Renaissance by introducing multiple perspectives into a two-dimensional image. Futurism incorporated the depiction of movement and machine age imagery. Dadaism's most notable exponents included Marcel Duchamp, who rejected conventional art styles altogether by exhibiting found objects (notably a urinal), and Francis Picabia with his Portraits Mécaniques.

RECOMMENDED READING:

The updated 2004 edition in quality soft cover; used copies available:

Robert Hughes,

The Shock of the New: Art and the Century of Change,

Thames & Hudson,

ISBN 0500275823