Week 21

Week 21: Wednesday, April 2, 2025

Daniel Boone

WEEK 21

Daniel Boone

"It was on the first of May, in the year 1769, that I resigned my domestic happiness for a time, and left my family and peaceable habitation on the Yadkin River, in North-Carolina, to wander through the wilderness of America, in quest of the country of Kentucke…"—Daniel Boone, in John Filson’s The Discovery, 1784

Daniel Boone (1734 – 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyond the western borders of the Thirteen Colonies. In 1775, Boone blazed the Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap and into Kentucky, in the face of resistance from American Indians, for whom the area was a traditional hunting ground. He founded Boonesborough, one of the first English-speaking settlements west of the Appalachian Mountains. By the end of the 18th century, more than 200,000 people had entered Kentucky by following the route marked by Boone. Boone served as a militia officer during the Revolutionary War (1775–1783), which was fought in Kentucky primarily between American settlers and British-allied Indians. Boone was taken in by Shawnees in 1778 and adopted into the tribe, but he resigned and continued to help protect the Kentucky settlements. He also left due to the Shawnee Indians torturing and killing one of his sons. He was elected to the first of his three terms in the Virginia General Assembly during the war and fought in the Battle of Blue Licks in 1782, one of the last battles of the American Revolution. He worked as a surveyor and merchant after the war, but he went deep into debt as a Kentucky land speculator. He resettled in Missouri in 1799, where he spent most of the last two decades of his life, frustrated with legal problems resulting from his land claims. Boone remains an iconic, if imperfectly remembered, figure in American history. He was a legend in his own lifetime, especially after an account of his adventures was published in 1784, making him famous in America and Europe. After his death, he became the subject of many heroic tall tales and works of fiction. His adventures—real and legendary—helped create the archetypal frontier hero of American folklore. In American popular culture, Boone is remembered as one of the foremost early frontiersmen, even though mythology often overshadows the historical details of his life.[4]

BRUCE THOMPSON:

"As we all know, the thirteen original colonies hugged the Atlantic shore. Moreover, they were hemmed in by Appalachian Mountains, and, further to the west, by other claimants to the vast, uncharted land on the other side of those mountains: Native Americans, the Spanish, the French, and the British. But the Founders were obsessed with the West from the beginning. George Washington, a surveyor by profession before he was a soldier, never heard of a land deal that did not tempt him. Before the Revolution, Washington owned over 63,000 acres of trans-Appalachia, and he wanted more. So did Thomas Jefferson, who built Monticello facing west. British efforts to stem the flow of Virginians across the mountains were among the principal causes of the Revolution. Richard Henderson, a judge in North Carolina and a sponsor of Daniel Boone’s scouting expeditions, possessed, in his own words, "a rapturous idea of property." During the years before the Revolution, and for many years after it, speculation in property was considered an honorable way of getting rich. Why this obsession? Stephen Ambrose explains: "constant expansion was critical, because the Virginia plantation of the day was incredibly wasteful. The low ground or inferior bottomland was planted to corn to provide food for slaves and animals. Fertile land—identified by hardwood growth—was saved for tobacco. The planters had their slaves gird large trees and leave the trees to die while plowing lightly around them. Slaves created hills for tobacco with a hoe, without bothering to remove the trees. After three annual crops of tobacco, these ‘fields’ grew wheat for a year or so before being abandoned and allowed to revert to pine forest. The planters let their stock roam wild, made no use of animal manure, and practiced only the most rudimentary crop rotation. Meanwhile, the planters moved their slaves to virgin lands and repeated the process. The system allowed the planters to use to the maximum the two things in which they were really rich, land and slaves. Tobacco, their only cash crop, was dependent on an all-but-unlimited quantity of each…. Tobacco wore out land so fast there could never be enough." But it wasn’t only wealthy planters who sought land. Land hunger was universal. For people of modest means, or even no means at all, the acquisition and development of fertile land was an attainable goal. It’s true that lack of capital, labor-intensive farming, and poor transportation limited most farmers to a subsistence level, but this was better than most European peasants could hope for. Americans, the great historian David Potter observed, were the "people of plenty." Another fine American historian, John Opie, writes: "One of the world’s great agricultural success stories took hold when the independent property-owning farmer appeared on the American landscape. This legendary figure dominated American expansion westward…. The frontier farmer remained undertooled, undercapitalized, and isolated, but the American landscape, with its fertile soil and forgiving climate, was the foundation for a remarkable shift from scarcity to an abundance of food…. In southern Pennsylvania, Daniel Boone’s father, blocked by the mountains from easy access to the west, gathered up six of his eight children and several grandchildren and drifted southward to base of the Appalachians: the Shenandoah Valley. There, the Boones and other migrants from Pennsylvania joined another stream of settlers pushing up from South Carolina northward along the rivers that flow from the Blue Ridge Mountains. Many of them were Scotch-Irish, deeply imbued with Calvinism; some were Huguenots from France or Germans from the Rhine Palatinate. They were, as a group, semi-literate, tough, and cantankerous. Their assets: perhaps an axe, a hunting knife, an auger, a rifle, a horse or two, some cattle and pigs, a sack of seed corn and another of salt, a crosscut saw, and a loom. Before they could establish their farms, they lived on wild meat, Indian maize, and native fruits. Land for them meant dignity and independence, and they hoped, eventually, prosperity. On May 1, 1769, Daniel Boone and his party moved west across the headwater streams of the Tennessee River and found the Warrior’s Trace, by which Cherokee war parties traveled north as far as the shores of Lake Erie. They traveled north through the rocky, steep-sided Cumberland Gap, to the open prairies that later became known as the bluegrass country of Kentucky. And what did they report, when they returned in the spring of 1771? "Horses trampling through the wild strawberries; the gaps were stained with juice to their knees. Grapevines a foot thick spread lofty tendrils through the dense canopy of forest leaves; the way to pick grapes was to chop down the trees. And game! Pigeon roosts were a thousand acres in size. Wild turkeys were so fat that when they were shot and fell to the ground, their skins burst open. Deer, elk, and buffalo came in fantastic numbers to the ‘licks’—salt-impregnated earth surrounding saline springs…. By the time of the Revolution, the rich lands of Kentucky had become a patchwork of conflicting land claims. That is why Abraham Lincoln’s father, Thomas, having cleared a patch of land and tried to establish himself there, had to abandon it and move further west."

RECOMMENDED READING

Bob and Tom Drury and Clavin,

Blood and Treasure: Daniel Boone and the Fight for America's First Frontier,

St Martin's Press,

ISBN 978-1250247131

RECOMENDED READING

Renowned storyteller Dee Brown, author of the bestselling Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, recreates the struggles of Native Americans, settlers, and ranchers in this stunning volume that illuminates the history of the old West that’s filled with maps and vintage photographs. Beginning with the demise of the Native Americans of the Plains, Brown depicts the onrush of the burgeoning cattle trade and the waves of immigrants who ultimately “settled” the land. In the retelling of this oft-told saga, Brown has demonstrated once again his abilities as a master storyteller and an entertaining popular historian. By turns heroic, tragic, and even humorous, The American West brings to life American tragedy and triumph in the years from 1840 to the turn of the century, and a roster of characters both great and small: Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, Geronimo, Dull Knife, Crazy Horse, Captain Jack, John H. Tunstall, Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett, Wyatt Earp, the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang, Wild Bill Hickok, Charles Goodnight, Oliver Loving, Buffalo Bill, and many others.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

22

Week 22: Wednesday, April 9, 2025

Lewis and Clark

WEEK 22

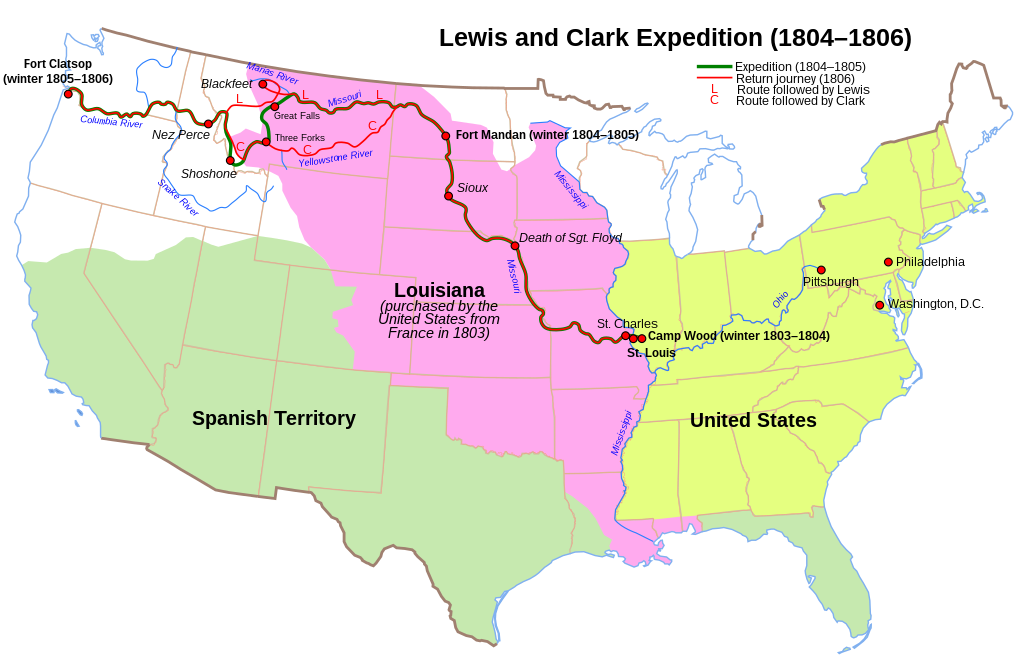

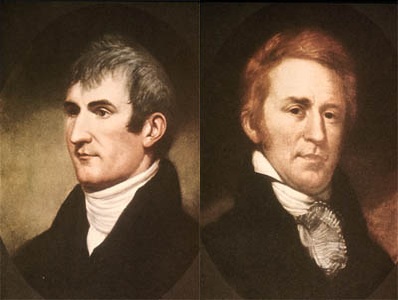

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select group of U.S. Army and civilian volunteers under the command of Captain Meriwether Lewis and his close friend Second Lieutenant William Clark. Clark and 30 members set out from Camp Dubois (Camp Wood), Illinois, on May 14, 1804, met Lewis and ten other members of the group in St. Charles, Missouri, then went up the Missouri River. The expedition crossed the Continental Divide of the Americas near the Lemhi Pass, eventually coming to the Columbia River, and the Pacific Ocean in 1805. The return voyage began on March 23, 1806, at Fort Clatsop, Oregon, and ended on September 23 of the same year. President Thomas Jefferson commissioned the expedition shortly after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 to explore and to map the newly acquired territory, to find a practical route across the western half of the continent, and to establish an American presence in this territory before European powers attempted to establish claims in the region. The campaign's secondary objectives were scientific and economic: to study the area's plants, animal life, and geography, and to establish trade with local Native American tribes. The expedition returned to St. Louis to report its findings to Jefferson, with maps, sketches, and journals in hand. (Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

23

Week 23: Wednesday, April 16, 2025

Tecumseh

WEEK 23

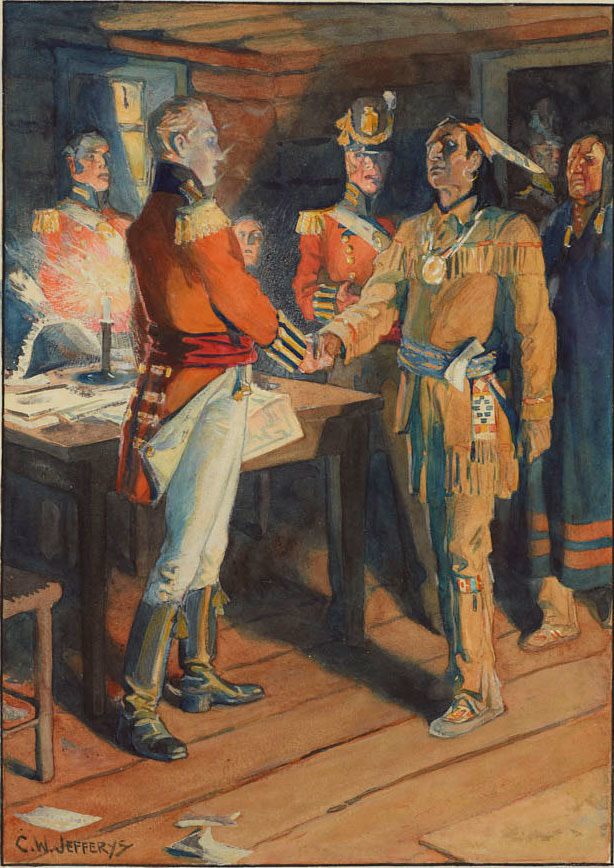

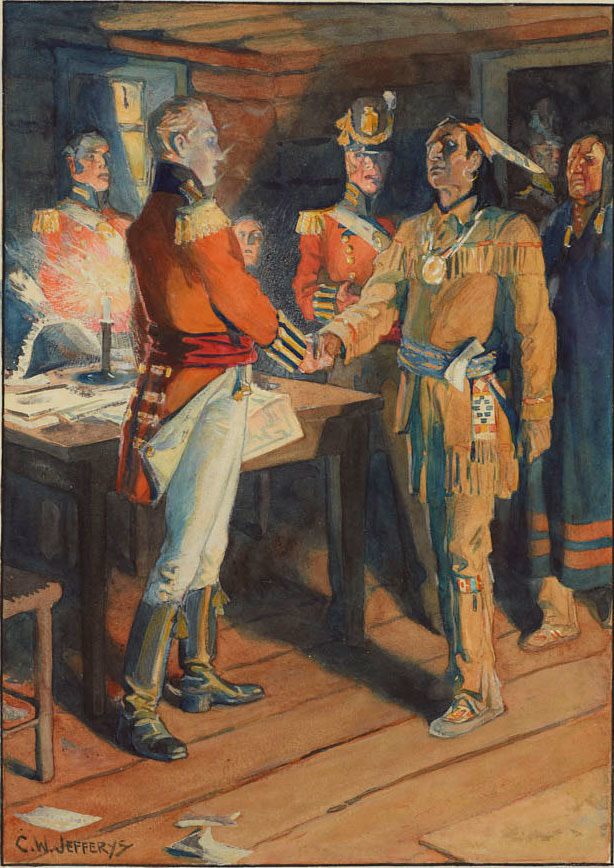

Tecumseh (1768 – 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and promoting intertribal unity. Even though his efforts to unite Native Americans ended with his death in the War of 1812, he became an iconic folk hero in American, Indigenous, and Canadian popular history. Tecumseh was born in what is now Ohio at a time when the far-flung Shawnees were reuniting in their Ohio Country homeland. During his childhood, the Shawnees lost territory to the expanding American colonies in a series of border conflicts. Tecumseh's father was killed in battle against American colonists in 1774. Tecumseh was thereafter mentored by his older brother Cheeseekau, a noted war chief who died fighting Americans in 1792. As a young war leader, Tecumseh joined Shawnee Chief Blue Jacket's armed struggle against further American encroachment, which ended in defeat at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 and with the loss of most of Ohio in the 1795 Treaty of Greenville. In 1805, Tecumseh's younger brother Tenskwatawa, who came to be known as the Shawnee Prophet, founded a religious movement that called upon Native Americans to reject European influences and return to a more traditional lifestyle. In 1808, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa established Prophetstown, a village in present-day Indiana, that grew into a large, multi-tribal community. Tecumseh traveled constantly, spreading the Prophet's message and eclipsing his brother in prominence. Tecumseh proclaimed that Native Americans owned their lands in common and urged tribes not to cede more territory unless all agreed. His message alarmed American leaders as well as Native leaders who sought accommodation with the United States. In 1811, when Tecumseh was in the South recruiting allies, Americans under William Henry Harrison defeated Tenskwatawa at the Battle of Tippecanoe and destroyed Prophetstown. In the War of 1812, Tecumseh joined his cause with the British, recruited warriors, and helped capture Detroit in August 1812. The following year he led an unsuccessful campaign against the United States in Ohio and Indiana. When U.S. naval forces took control of Lake Erie in 1813, Tecumseh reluctantly retreated with the British into Upper Canada, where American forces engaged them at the Battle of the Thames on October 5, 1813, in which Tecumseh was killed. His death caused his confederacy to collapse. The lands he had fought to defend were eventually ceded to the U.S. government. His legacy as one of the most celebrated Native Americans in history grew in the years after his death, although details of his life have often been obscured by mythology.(Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

From the Publisher:

"For too long we’ve lacked a compact, inexpensive, authoritative, and compulsively readable book that offers American readers a clear, informative, and inspiring narrative account of their country. Such a fresh retelling of the American story is especially needed today, to shape and deepen young Americans’ sense of the land they inhabit, help them to understand its roots and share in its memories, all the while equipping them for the privileges and responsibilities of citizenship in American society. The existing texts simply fail to tell that story with energy and conviction. Too often they reflect a fragmented outlook that fails to convey to American readers the grand trajectory of their own history. A great nation needs and deserves a great and coherent narrative, as an expression of its own self-understanding and its aspirations; and it needs to be able to convey that narrative effectively. Of course, it goes without saying that such a narrative cannot be a fairy tale of the past. It will not be convincing if it is not truthful. But as Land of Hope brilliantly shows, there is no contradiction between a truthful account of the American past and an inspiring one. Readers of Land of Hope will find both in its pages."

24

Week 24: Wednesday, April 23, 2025

Andrew Jackson

WEEK 24

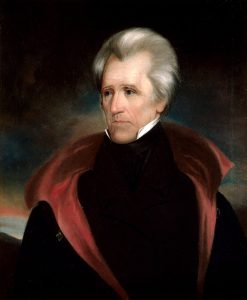

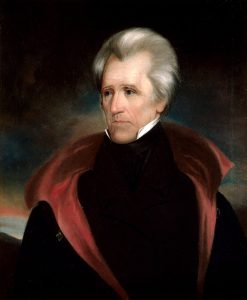

Andrew Jackson (1767 – 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before his presidency, he gained fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses of the U.S. Congress. Often praised as an advocate for ordinary Americans and for his work in preserving the union of states, Jackson has also been criticized for his racial policies, particularly his treatment of Native Americans. Jackson was born in the colonial Carolinas before the American Revolutionary War. He became a frontier lawyer and married Rachel Donelson Robards. He briefly served in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate, representing Tennessee. After resigning, he served as a justice on the Tennessee Superior Court from 1798 until 1804. Jackson purchased a property later known as the Hermitage, becoming a wealthy planter who owned hundreds of African-American slaves during his lifetime. In 1801, he was appointed colonel of the Tennessee militia and was elected its commander. He led troops during the Creek War of 1813–1814, winning the Battle of Horseshoe Bend and negotiating the Treaty of Fort Jackson that required the indigenous Creek population to surrender vast tracts of present-day Alabama and Georgia. In the concurrent war against the British, Jackson's victory at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815 made him a national hero. He later commanded U.S. forces in the First Seminole War, which led to the annexation of Florida from Spain. Jackson briefly served as Florida's first territorial governor before returning to the Senate. He ran for president in 1824. He won a plurality of the popular and electoral vote, but no candidate won the electoral majority. With the help of Henry Clay, the House of Representatives elected John Quincy Adams in a contingent election. Jackson's supporters alleged that there was a "corrupt bargain" between Adams and Clay and began creating their own political organization that would eventually become the Democratic Party. Jackson ran again in 1828, defeating Adams in a landslide. In 1830, he signed the Indian Removal Act. This act displaced tens of thousands of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands east of the Mississippi and resulted in thousands of deaths. Jackson faced a challenge to the integrity of the federal union when South Carolina threatened to nullify a high protective tariff set by the federal government. He threatened the use of military force to enforce the tariff, but the crisis was defused when it was amended. In 1832, he vetoed a bill by Congress to reauthorize the Second Bank of the United States, arguing that it was a corrupt institution. After a lengthy struggle, the Bank was dismantled. In 1835, Jackson became the only president to pay off the national debt. He survived the first assassination attempt on a sitting president. In one of his final presidential acts, he recognized the Republic of Texas. After leaving office, Jackson supported the presidencies of Martin Van Buren and James K. Polk, as well as the annexation of Texas. Jackson's legacy remains controversial, and opinions are frequently polarized. Supporters characterize him as a defender of democracy and the Constitution, while critics point to his reputation as a demagogue who ignored the law when it suited him. Jackson's presidency has consistently been ranked as above average, although his reputation has declined since the late 20th century.

(Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

25

Week 25: Wednesday, April 30, 2025

President Andrew Jackson

WEEK 25

Jackson spent much of his time during his first two and a half years in office dealing with what came to be known as the "Petticoat Affair" or "Eaton Affair". The affair focused on Secretary of War Eaton's wife, Margaret. She had a reputation for being promiscuous, and like Rachel Jackson, she was accused of adultery. She and Eaton had been close before her first husband John Timberlake died, and they married nine months after his death. With the exception of Barry's wife Catherine, the cabinet members' wives followed the lead of Vice-president Calhoun's wife Floride and refused to socialize with the Eatons.[206] Though Jackson defended Margaret, her presence split the cabinet, which had been so ineffective that he rarely called it into session,[189] and the ongoing disagreement led to its dissolution. In the spring of 1831, Jackson demanded the resignations of all the cabinet members except Barry, who would resign in 1835 when a Congressional investigation revealed his mismanagement of the Post Office. Jackson tried to compensate Van Buren by appointing him the Minister to Great Britain, but Calhoun blocked the nomination with a tie-breaking vote against it. Van Buren—along with newspaper editors Amos Kendall and Francis Preston Blair would become regular participants in Jackson's Kitchen Cabinet, an unofficial, varying group of advisors that Jackson turned to for decision making even after he had formed a new official cabinet.

26

Week 26: Wednesday, May 7, 2025

Indian Removal Act of 1830

WEEK 26

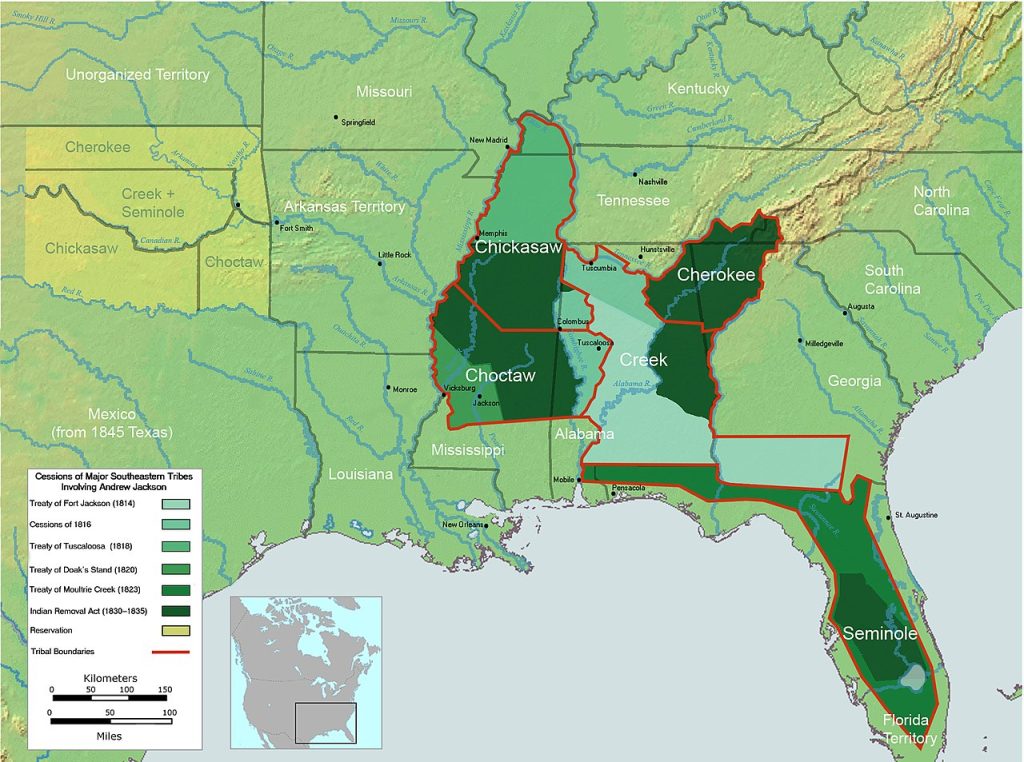

Indian Removal Act of 1830

The Indian Removal Act and treaties involving Jackson before his presidency displaced most of the major tribes of the Southeast from their traditional territories east of the Mississippi River. Jackson's presidency marked the beginning of a national policy of Native American removal. Before Jackson took office, the relationship between the southern states and the Native American tribes who lived within their boundaries was strained. The states felt that they had full jurisdiction over their territories; the native tribes saw themselves as autonomous nations that had a right to the land they lived on. Significant portions of the five major tribes in the area then known as the Southwest—the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminoles— began to adopt white culture, including education, agricultural techniques, a road system, and rudimentary manufacturing. In the case of the tensions between the state of Georgia and the Cherokee, Adams had tried to address the issue encouraging Cherokee emigration west of the Mississippi through financial incentives, but most refused.

In the first days of Jackson's presidency, some southern states passed legislation extending state jurisdiction to Native American lands. Jackson supported the states' right to do so. His position was later made clear in the 1832 Supreme Court test case of this legislation, Worcester v. Georgia. Georgia had arrested a group of missionaries for entering Cherokee territory without a permit; the Cherokee declared these arrests illegal. The court under Chief Justice John Marshall decided in favor of the Cherokee: imposition of Georgia law on the Cherokee was unconstitutional. Horace Greeley alleges that when Jackson heard the ruling, he said, "Well, John Marshall has made his decision, but now let him enforce it." Although the quote may be apocryphal, Jackson made it clear he would not use the federal government to enforce the ruling. Jackson used the power of the federal government to enforce the separation of Indigenous tribes and whites. In May 1830, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which Congress had narrowly passed. It gave the president the right to negotiate treaties to buy tribal lands in the eastern part of the United States in exchange for lands set aside for Native Americans west of the Mississippi, as well as broad discretion on how to use the federal funds allocated to the negotiations. The law was supposed to be a voluntary relocation program, but it was not implemented as one. Jackson's administration often achieved agreement to relocate through bribes, fraud and intimidation, and the leaders who signed the treaties often did not represent the entire tribe. The relocations could be a source of misery too: the Choctaw relocation was rife with corruption, theft, and mismanagement that brought great suffering to that people. In 1830, Jackson personally negotiated with the Chickasaw, who quickly agreed to move. In the same year, Choctaw leaders signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek; the majority did not want the treaty but complied with its terms. In 1832, Seminole leaders signed the Treaty of Payne's Landing, which stipulated that the Seminoles would move west and become part of the Muscogee Creek Confederacy if they found the new land suitable. Most Seminoles refused to move, leading to the Second Seminole War in 1835 that lasted six years. Members of the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ceded their land to the state of Alabama in the Treaty of Cusseta of 1832. Their private ownership of the land was to be protected, but the federal government did not enforce this. The government did encourage voluntary removal until the Creek War of 1836, after which almost all Creek were removed to Oklahoma territory. In 1836, Cherokee leaders ceded their land to the government by the Treaty of New Echota. Their removal, known as the Trail of Tears, was enforced by Jackson's successor, Van Buren. Jackson also applied the removal policy in the Northwest. He was not successful in removing the Iroquois Confederacy in New York, but when some members of the Meskwaki (Fox) and the Sauk triggered the Black Hawk War by trying to cross back to the east side of the Mississippi, the peace treaties ratified after their defeat reduced their lands further. During his administration, he made about 70 treaties with American Indian tribes. He had removed almost all the Native Americans east of the Mississippi and south of Lake Michigan, about 70,000 people, from the United States; though it was done at the cost of thousands of Native American lives lost because of the unsanitary conditions and epidemics arising from their dislocation, as well as their resistance to expulsion. Jackson's implementation of the Indian Removal Act contributed to his popularity with his constituency. He added over 170,000 square miles of land to the public domain, which primarily benefited the United States' agricultural interests. The act also benefited small farmers, as Jackson allowed them to purchase moderate plots at low prices and offered squatters on land formerly belonging to Native Americans the option to purchase it before it was offered for sale to others.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

27

Week 27: Wednesday, May 14, 2025

Texas and Sam Houston

WEEK 27

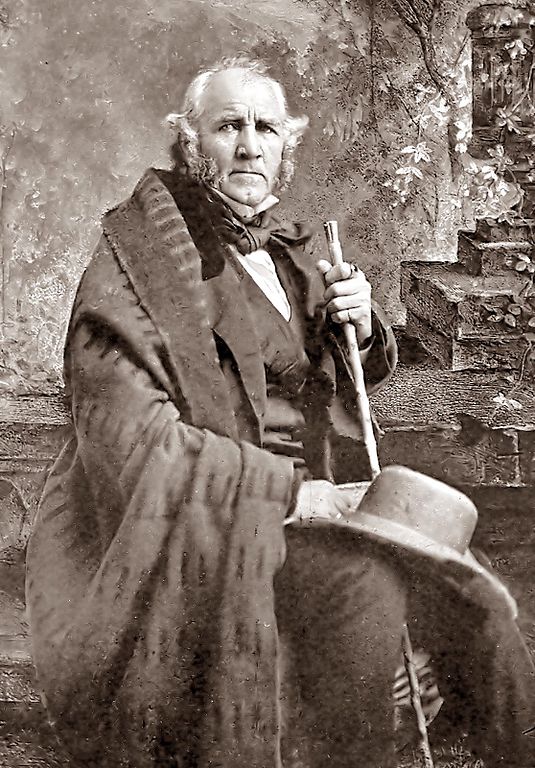

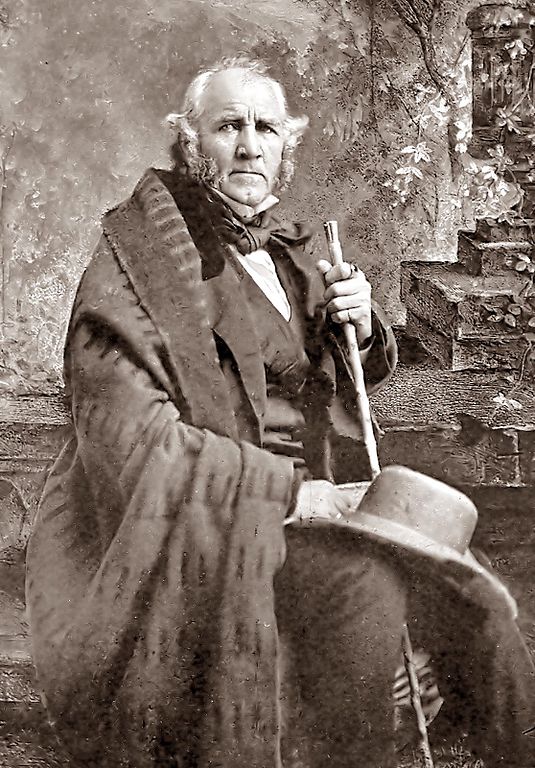

Samuel Houston (March 2, 1793 – July 26, 1863) was an American general and statesman who played a prominent role in the Texas Revolution. He served as the first and third president of the Republic of Texas and was one of the first two individuals to represent Texas in the United States Senate. He also served as the sixth governor of Tennessee and the seventh governor of Texas, the only individual to be elected governor of two different states in the United States.

28

Week 28: Wednesday, May 21, 2025

The Mexican-American War

WEEK 28

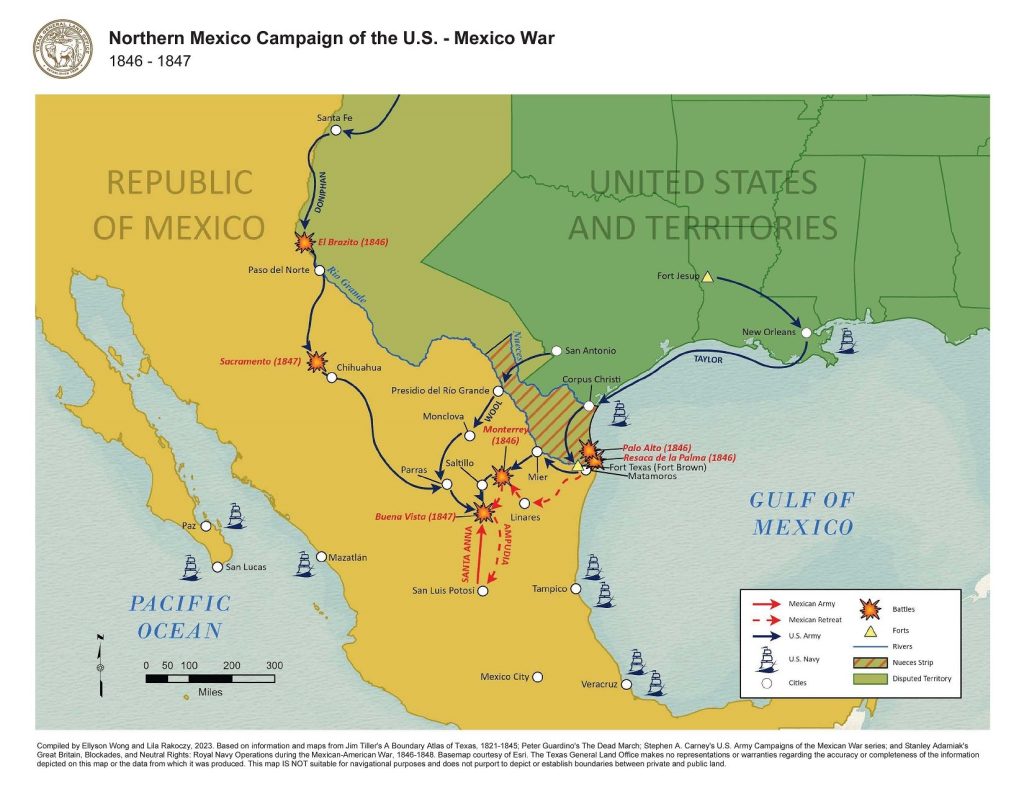

The Mexican–American War was an invasion of Mexico by the United States Army from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1845 American annexation of Texas, which Mexico still considered its territory because Mexico refused to recognize the Treaties of Velasco, signed by President Antonio López de Santa Anna after he was captured by the Texian Army during the 1836 Texas Revolution. The Republic of Texas was de facto an independent country, but most of its Anglo-American citizens who had moved from the United States to Texas after 1822 wanted to be annexed by the United States. In the United States, sectional politics over slavery had previously prevented annexation because Texas, formerly a slavery-free territory under Mexican rule, would have been admitted as a slave state, upsetting the balance of power between Northern free states and Southern slave states. In the 1844 United States presidential election, Democrat James K. Polk was elected on a platform of expanding U.S. territory to Oregon, California, and Texas by any means, with the 1845 annexation of Texas furthering that goal.

29

Week 29: Wednesday, May 28, 2025

California 1849

WEEK 29

Prior to European colonization, California was one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse areas in pre-Columbian North America. European exploration in the 16th and 17th centuries led to the colonization by the Spanish Empire. The area became a part of Mexico in 1821, following its successful war for independence, but was ceded to the United States in 1848 after the Mexican–American War. The California Gold Rush started in 1848 and led to social and demographic changes. The western portion of Alta California was then organized and admitted as the 31st state in 1850, as a free state, following the Compromise of 1850.

30

Week 30: Wednesday, June 4, 2025

The Western

WEEK 30

The Western

BRUCE THOMPSON (UCSC)

The open range for cattle drives lasted less than a quarter of a century after the Civil War, and the last major Indian war ended in 1890 with the defeat of the Sioux at Wounded Knee. In 1890, the US Census Bureau announced the closing of the frontier. Yet for more than half of the century that followed, the Western was one of the pillars of American popular culture, first on the stage (Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show, in literature (starting with Owen Wister’s The Virginian, 1902), cinema (starting with Cecil B. DeMille’s The Squaw Man in 1914), and on television (Westerns were the dominant genre through the first half of the 1960s). How do we account for this extraordinarily long and rich afterlife of the frontier in American popular culture? Why did so many of the finest and most influential American directors (John Ford, Howard Hawks, Anthony Mann, George Stevens) and actors (Gary Cooper, John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, Henry Fonda, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, Robert Ryan, Glenn Ford, Van Heflin, Clint Eastwood) do so much of their best work in this genre? What exactly was "the Western," and how did it evolve? A preliminary answer: the Western offered attractive versions of heroism, placed within a historical context that seemed to evoke something essential about our "national character." The great popularity of the genre, writes Forrest Robinson in his book Having It Both Ways: Self-subversion in Western Popular Classics, "is quite obviously the result of this emphasis on the heroic, with its abundance of vigorous action in colorful settings, and its attention to such values as courage, independence, self-reliance, and the stoical indifference to pain." But having established these values as central to our national self-image, the writers and film directors who developed the canon of Western literature and cinema then proceeded to complicate them: revising the stereotypes, and sometimes subverting them. And sometimes, as in the books of Elmore Leonard and Cormac McCarthy, and the films of Ford, Hawks, Mann, and Stevens, they have produced works of art that both celebrate and criticize our culture at the same time.

RECOMMENDED READING

Renowned storyteller Dee Brown, author of the bestselling Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, recreates the struggles of Native Americans, settlers, and ranchers in this stunning volume that illuminates the history of the old West that’s filled with maps and vintage photographs. Beginning with the demise of the Native Americans of the Plains, Brown depicts the onrush of the burgeoning cattle trade and the waves of immigrants who ultimately “settled” the land. In the retelling of this oft-told saga, Brown has demonstrated once again his abilities as a master storyteller and an entertaining popular historian. By turns heroic, tragic, and even humorous, The American West brings to life American tragedy and triumph in the years from 1840 to the turn of the century, and a roster of characters both great and small: Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, Geronimo, Dull Knife, Crazy Horse, Captain Jack, John H. Tunstall, Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett, Wyatt Earp, the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang, Wild Bill Hickok, Charles Goodnight, Oliver Loving, Buffalo Bill, and many others.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

All

Week 21: Wed., Apr. 2, 2025

Daniel Boone

WEEK 21

Daniel Boone

"It was on the first of May, in the year 1769, that I resigned my domestic happiness for a time, and left my family and peaceable habitation on the Yadkin River, in North-Carolina, to wander through the wilderness of America, in quest of the country of Kentucke…"—Daniel Boone, in John Filson’s The Discovery, 1784

Daniel Boone (1734 – 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyond the western borders of the Thirteen Colonies. In 1775, Boone blazed the Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap and into Kentucky, in the face of resistance from American Indians, for whom the area was a traditional hunting ground. He founded Boonesborough, one of the first English-speaking settlements west of the Appalachian Mountains. By the end of the 18th century, more than 200,000 people had entered Kentucky by following the route marked by Boone. Boone served as a militia officer during the Revolutionary War (1775–1783), which was fought in Kentucky primarily between American settlers and British-allied Indians. Boone was taken in by Shawnees in 1778 and adopted into the tribe, but he resigned and continued to help protect the Kentucky settlements. He also left due to the Shawnee Indians torturing and killing one of his sons. He was elected to the first of his three terms in the Virginia General Assembly during the war and fought in the Battle of Blue Licks in 1782, one of the last battles of the American Revolution. He worked as a surveyor and merchant after the war, but he went deep into debt as a Kentucky land speculator. He resettled in Missouri in 1799, where he spent most of the last two decades of his life, frustrated with legal problems resulting from his land claims. Boone remains an iconic, if imperfectly remembered, figure in American history. He was a legend in his own lifetime, especially after an account of his adventures was published in 1784, making him famous in America and Europe. After his death, he became the subject of many heroic tall tales and works of fiction. His adventures—real and legendary—helped create the archetypal frontier hero of American folklore. In American popular culture, Boone is remembered as one of the foremost early frontiersmen, even though mythology often overshadows the historical details of his life.[4]

BRUCE THOMPSON:

"As we all know, the thirteen original colonies hugged the Atlantic shore. Moreover, they were hemmed in by Appalachian Mountains, and, further to the west, by other claimants to the vast, uncharted land on the other side of those mountains: Native Americans, the Spanish, the French, and the British. But the Founders were obsessed with the West from the beginning. George Washington, a surveyor by profession before he was a soldier, never heard of a land deal that did not tempt him. Before the Revolution, Washington owned over 63,000 acres of trans-Appalachia, and he wanted more. So did Thomas Jefferson, who built Monticello facing west. British efforts to stem the flow of Virginians across the mountains were among the principal causes of the Revolution. Richard Henderson, a judge in North Carolina and a sponsor of Daniel Boone’s scouting expeditions, possessed, in his own words, "a rapturous idea of property." During the years before the Revolution, and for many years after it, speculation in property was considered an honorable way of getting rich. Why this obsession? Stephen Ambrose explains: "constant expansion was critical, because the Virginia plantation of the day was incredibly wasteful. The low ground or inferior bottomland was planted to corn to provide food for slaves and animals. Fertile land—identified by hardwood growth—was saved for tobacco. The planters had their slaves gird large trees and leave the trees to die while plowing lightly around them. Slaves created hills for tobacco with a hoe, without bothering to remove the trees. After three annual crops of tobacco, these ‘fields’ grew wheat for a year or so before being abandoned and allowed to revert to pine forest. The planters let their stock roam wild, made no use of animal manure, and practiced only the most rudimentary crop rotation. Meanwhile, the planters moved their slaves to virgin lands and repeated the process. The system allowed the planters to use to the maximum the two things in which they were really rich, land and slaves. Tobacco, their only cash crop, was dependent on an all-but-unlimited quantity of each…. Tobacco wore out land so fast there could never be enough." But it wasn’t only wealthy planters who sought land. Land hunger was universal. For people of modest means, or even no means at all, the acquisition and development of fertile land was an attainable goal. It’s true that lack of capital, labor-intensive farming, and poor transportation limited most farmers to a subsistence level, but this was better than most European peasants could hope for. Americans, the great historian David Potter observed, were the "people of plenty." Another fine American historian, John Opie, writes: "One of the world’s great agricultural success stories took hold when the independent property-owning farmer appeared on the American landscape. This legendary figure dominated American expansion westward…. The frontier farmer remained undertooled, undercapitalized, and isolated, but the American landscape, with its fertile soil and forgiving climate, was the foundation for a remarkable shift from scarcity to an abundance of food…. In southern Pennsylvania, Daniel Boone’s father, blocked by the mountains from easy access to the west, gathered up six of his eight children and several grandchildren and drifted southward to base of the Appalachians: the Shenandoah Valley. There, the Boones and other migrants from Pennsylvania joined another stream of settlers pushing up from South Carolina northward along the rivers that flow from the Blue Ridge Mountains. Many of them were Scotch-Irish, deeply imbued with Calvinism; some were Huguenots from France or Germans from the Rhine Palatinate. They were, as a group, semi-literate, tough, and cantankerous. Their assets: perhaps an axe, a hunting knife, an auger, a rifle, a horse or two, some cattle and pigs, a sack of seed corn and another of salt, a crosscut saw, and a loom. Before they could establish their farms, they lived on wild meat, Indian maize, and native fruits. Land for them meant dignity and independence, and they hoped, eventually, prosperity. On May 1, 1769, Daniel Boone and his party moved west across the headwater streams of the Tennessee River and found the Warrior’s Trace, by which Cherokee war parties traveled north as far as the shores of Lake Erie. They traveled north through the rocky, steep-sided Cumberland Gap, to the open prairies that later became known as the bluegrass country of Kentucky. And what did they report, when they returned in the spring of 1771? "Horses trampling through the wild strawberries; the gaps were stained with juice to their knees. Grapevines a foot thick spread lofty tendrils through the dense canopy of forest leaves; the way to pick grapes was to chop down the trees. And game! Pigeon roosts were a thousand acres in size. Wild turkeys were so fat that when they were shot and fell to the ground, their skins burst open. Deer, elk, and buffalo came in fantastic numbers to the ‘licks’—salt-impregnated earth surrounding saline springs…. By the time of the Revolution, the rich lands of Kentucky had become a patchwork of conflicting land claims. That is why Abraham Lincoln’s father, Thomas, having cleared a patch of land and tried to establish himself there, had to abandon it and move further west."

RECOMMENDED READING

Bob and Tom Drury and Clavin,

Blood and Treasure: Daniel Boone and the Fight for America's First Frontier,

St Martin's Press,

ISBN 978-1250247131

RECOMENDED READING

Renowned storyteller Dee Brown, author of the bestselling Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, recreates the struggles of Native Americans, settlers, and ranchers in this stunning volume that illuminates the history of the old West that’s filled with maps and vintage photographs. Beginning with the demise of the Native Americans of the Plains, Brown depicts the onrush of the burgeoning cattle trade and the waves of immigrants who ultimately “settled” the land. In the retelling of this oft-told saga, Brown has demonstrated once again his abilities as a master storyteller and an entertaining popular historian. By turns heroic, tragic, and even humorous, The American West brings to life American tragedy and triumph in the years from 1840 to the turn of the century, and a roster of characters both great and small: Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, Geronimo, Dull Knife, Crazy Horse, Captain Jack, John H. Tunstall, Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett, Wyatt Earp, the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang, Wild Bill Hickok, Charles Goodnight, Oliver Loving, Buffalo Bill, and many others.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

Week 22: Wed., Apr. 9, 2025

Lewis and Clark

WEEK 22

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select group of U.S. Army and civilian volunteers under the command of Captain Meriwether Lewis and his close friend Second Lieutenant William Clark. Clark and 30 members set out from Camp Dubois (Camp Wood), Illinois, on May 14, 1804, met Lewis and ten other members of the group in St. Charles, Missouri, then went up the Missouri River. The expedition crossed the Continental Divide of the Americas near the Lemhi Pass, eventually coming to the Columbia River, and the Pacific Ocean in 1805. The return voyage began on March 23, 1806, at Fort Clatsop, Oregon, and ended on September 23 of the same year. President Thomas Jefferson commissioned the expedition shortly after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 to explore and to map the newly acquired territory, to find a practical route across the western half of the continent, and to establish an American presence in this territory before European powers attempted to establish claims in the region. The campaign's secondary objectives were scientific and economic: to study the area's plants, animal life, and geography, and to establish trade with local Native American tribes. The expedition returned to St. Louis to report its findings to Jefferson, with maps, sketches, and journals in hand. (Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

Week 23: Wed., Apr. 16, 2025

Tecumseh

WEEK 23

Tecumseh (1768 – 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and promoting intertribal unity. Even though his efforts to unite Native Americans ended with his death in the War of 1812, he became an iconic folk hero in American, Indigenous, and Canadian popular history. Tecumseh was born in what is now Ohio at a time when the far-flung Shawnees were reuniting in their Ohio Country homeland. During his childhood, the Shawnees lost territory to the expanding American colonies in a series of border conflicts. Tecumseh's father was killed in battle against American colonists in 1774. Tecumseh was thereafter mentored by his older brother Cheeseekau, a noted war chief who died fighting Americans in 1792. As a young war leader, Tecumseh joined Shawnee Chief Blue Jacket's armed struggle against further American encroachment, which ended in defeat at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 and with the loss of most of Ohio in the 1795 Treaty of Greenville. In 1805, Tecumseh's younger brother Tenskwatawa, who came to be known as the Shawnee Prophet, founded a religious movement that called upon Native Americans to reject European influences and return to a more traditional lifestyle. In 1808, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa established Prophetstown, a village in present-day Indiana, that grew into a large, multi-tribal community. Tecumseh traveled constantly, spreading the Prophet's message and eclipsing his brother in prominence. Tecumseh proclaimed that Native Americans owned their lands in common and urged tribes not to cede more territory unless all agreed. His message alarmed American leaders as well as Native leaders who sought accommodation with the United States. In 1811, when Tecumseh was in the South recruiting allies, Americans under William Henry Harrison defeated Tenskwatawa at the Battle of Tippecanoe and destroyed Prophetstown. In the War of 1812, Tecumseh joined his cause with the British, recruited warriors, and helped capture Detroit in August 1812. The following year he led an unsuccessful campaign against the United States in Ohio and Indiana. When U.S. naval forces took control of Lake Erie in 1813, Tecumseh reluctantly retreated with the British into Upper Canada, where American forces engaged them at the Battle of the Thames on October 5, 1813, in which Tecumseh was killed. His death caused his confederacy to collapse. The lands he had fought to defend were eventually ceded to the U.S. government. His legacy as one of the most celebrated Native Americans in history grew in the years after his death, although details of his life have often been obscured by mythology.(Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

From the Publisher:

"For too long we’ve lacked a compact, inexpensive, authoritative, and compulsively readable book that offers American readers a clear, informative, and inspiring narrative account of their country. Such a fresh retelling of the American story is especially needed today, to shape and deepen young Americans’ sense of the land they inhabit, help them to understand its roots and share in its memories, all the while equipping them for the privileges and responsibilities of citizenship in American society. The existing texts simply fail to tell that story with energy and conviction. Too often they reflect a fragmented outlook that fails to convey to American readers the grand trajectory of their own history. A great nation needs and deserves a great and coherent narrative, as an expression of its own self-understanding and its aspirations; and it needs to be able to convey that narrative effectively. Of course, it goes without saying that such a narrative cannot be a fairy tale of the past. It will not be convincing if it is not truthful. But as Land of Hope brilliantly shows, there is no contradiction between a truthful account of the American past and an inspiring one. Readers of Land of Hope will find both in its pages."

Week 24: Wed., Apr. 23, 2025

Andrew Jackson

WEEK 24

Andrew Jackson (1767 – 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before his presidency, he gained fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses of the U.S. Congress. Often praised as an advocate for ordinary Americans and for his work in preserving the union of states, Jackson has also been criticized for his racial policies, particularly his treatment of Native Americans. Jackson was born in the colonial Carolinas before the American Revolutionary War. He became a frontier lawyer and married Rachel Donelson Robards. He briefly served in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate, representing Tennessee. After resigning, he served as a justice on the Tennessee Superior Court from 1798 until 1804. Jackson purchased a property later known as the Hermitage, becoming a wealthy planter who owned hundreds of African-American slaves during his lifetime. In 1801, he was appointed colonel of the Tennessee militia and was elected its commander. He led troops during the Creek War of 1813–1814, winning the Battle of Horseshoe Bend and negotiating the Treaty of Fort Jackson that required the indigenous Creek population to surrender vast tracts of present-day Alabama and Georgia. In the concurrent war against the British, Jackson's victory at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815 made him a national hero. He later commanded U.S. forces in the First Seminole War, which led to the annexation of Florida from Spain. Jackson briefly served as Florida's first territorial governor before returning to the Senate. He ran for president in 1824. He won a plurality of the popular and electoral vote, but no candidate won the electoral majority. With the help of Henry Clay, the House of Representatives elected John Quincy Adams in a contingent election. Jackson's supporters alleged that there was a "corrupt bargain" between Adams and Clay and began creating their own political organization that would eventually become the Democratic Party. Jackson ran again in 1828, defeating Adams in a landslide. In 1830, he signed the Indian Removal Act. This act displaced tens of thousands of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands east of the Mississippi and resulted in thousands of deaths. Jackson faced a challenge to the integrity of the federal union when South Carolina threatened to nullify a high protective tariff set by the federal government. He threatened the use of military force to enforce the tariff, but the crisis was defused when it was amended. In 1832, he vetoed a bill by Congress to reauthorize the Second Bank of the United States, arguing that it was a corrupt institution. After a lengthy struggle, the Bank was dismantled. In 1835, Jackson became the only president to pay off the national debt. He survived the first assassination attempt on a sitting president. In one of his final presidential acts, he recognized the Republic of Texas. After leaving office, Jackson supported the presidencies of Martin Van Buren and James K. Polk, as well as the annexation of Texas. Jackson's legacy remains controversial, and opinions are frequently polarized. Supporters characterize him as a defender of democracy and the Constitution, while critics point to his reputation as a demagogue who ignored the law when it suited him. Jackson's presidency has consistently been ranked as above average, although his reputation has declined since the late 20th century.

(Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

Week 25: Wed., Apr. 30, 2025

President Andrew Jackson

WEEK 25

Jackson spent much of his time during his first two and a half years in office dealing with what came to be known as the "Petticoat Affair" or "Eaton Affair". The affair focused on Secretary of War Eaton's wife, Margaret. She had a reputation for being promiscuous, and like Rachel Jackson, she was accused of adultery. She and Eaton had been close before her first husband John Timberlake died, and they married nine months after his death. With the exception of Barry's wife Catherine, the cabinet members' wives followed the lead of Vice-president Calhoun's wife Floride and refused to socialize with the Eatons.[206] Though Jackson defended Margaret, her presence split the cabinet, which had been so ineffective that he rarely called it into session,[189] and the ongoing disagreement led to its dissolution. In the spring of 1831, Jackson demanded the resignations of all the cabinet members except Barry, who would resign in 1835 when a Congressional investigation revealed his mismanagement of the Post Office. Jackson tried to compensate Van Buren by appointing him the Minister to Great Britain, but Calhoun blocked the nomination with a tie-breaking vote against it. Van Buren—along with newspaper editors Amos Kendall and Francis Preston Blair would become regular participants in Jackson's Kitchen Cabinet, an unofficial, varying group of advisors that Jackson turned to for decision making even after he had formed a new official cabinet.

Week 26: Wed., May. 7, 2025

Indian Removal Act of 1830

WEEK 26

Indian Removal Act of 1830

The Indian Removal Act and treaties involving Jackson before his presidency displaced most of the major tribes of the Southeast from their traditional territories east of the Mississippi River. Jackson's presidency marked the beginning of a national policy of Native American removal. Before Jackson took office, the relationship between the southern states and the Native American tribes who lived within their boundaries was strained. The states felt that they had full jurisdiction over their territories; the native tribes saw themselves as autonomous nations that had a right to the land they lived on. Significant portions of the five major tribes in the area then known as the Southwest—the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminoles— began to adopt white culture, including education, agricultural techniques, a road system, and rudimentary manufacturing. In the case of the tensions between the state of Georgia and the Cherokee, Adams had tried to address the issue encouraging Cherokee emigration west of the Mississippi through financial incentives, but most refused.

In the first days of Jackson's presidency, some southern states passed legislation extending state jurisdiction to Native American lands. Jackson supported the states' right to do so. His position was later made clear in the 1832 Supreme Court test case of this legislation, Worcester v. Georgia. Georgia had arrested a group of missionaries for entering Cherokee territory without a permit; the Cherokee declared these arrests illegal. The court under Chief Justice John Marshall decided in favor of the Cherokee: imposition of Georgia law on the Cherokee was unconstitutional. Horace Greeley alleges that when Jackson heard the ruling, he said, "Well, John Marshall has made his decision, but now let him enforce it." Although the quote may be apocryphal, Jackson made it clear he would not use the federal government to enforce the ruling. Jackson used the power of the federal government to enforce the separation of Indigenous tribes and whites. In May 1830, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which Congress had narrowly passed. It gave the president the right to negotiate treaties to buy tribal lands in the eastern part of the United States in exchange for lands set aside for Native Americans west of the Mississippi, as well as broad discretion on how to use the federal funds allocated to the negotiations. The law was supposed to be a voluntary relocation program, but it was not implemented as one. Jackson's administration often achieved agreement to relocate through bribes, fraud and intimidation, and the leaders who signed the treaties often did not represent the entire tribe. The relocations could be a source of misery too: the Choctaw relocation was rife with corruption, theft, and mismanagement that brought great suffering to that people. In 1830, Jackson personally negotiated with the Chickasaw, who quickly agreed to move. In the same year, Choctaw leaders signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek; the majority did not want the treaty but complied with its terms. In 1832, Seminole leaders signed the Treaty of Payne's Landing, which stipulated that the Seminoles would move west and become part of the Muscogee Creek Confederacy if they found the new land suitable. Most Seminoles refused to move, leading to the Second Seminole War in 1835 that lasted six years. Members of the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ceded their land to the state of Alabama in the Treaty of Cusseta of 1832. Their private ownership of the land was to be protected, but the federal government did not enforce this. The government did encourage voluntary removal until the Creek War of 1836, after which almost all Creek were removed to Oklahoma territory. In 1836, Cherokee leaders ceded their land to the government by the Treaty of New Echota. Their removal, known as the Trail of Tears, was enforced by Jackson's successor, Van Buren. Jackson also applied the removal policy in the Northwest. He was not successful in removing the Iroquois Confederacy in New York, but when some members of the Meskwaki (Fox) and the Sauk triggered the Black Hawk War by trying to cross back to the east side of the Mississippi, the peace treaties ratified after their defeat reduced their lands further. During his administration, he made about 70 treaties with American Indian tribes. He had removed almost all the Native Americans east of the Mississippi and south of Lake Michigan, about 70,000 people, from the United States; though it was done at the cost of thousands of Native American lives lost because of the unsanitary conditions and epidemics arising from their dislocation, as well as their resistance to expulsion. Jackson's implementation of the Indian Removal Act contributed to his popularity with his constituency. He added over 170,000 square miles of land to the public domain, which primarily benefited the United States' agricultural interests. The act also benefited small farmers, as Jackson allowed them to purchase moderate plots at low prices and offered squatters on land formerly belonging to Native Americans the option to purchase it before it was offered for sale to others.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

Week 27: Wed., May. 14, 2025

Texas and Sam Houston

WEEK 27

Samuel Houston (March 2, 1793 – July 26, 1863) was an American general and statesman who played a prominent role in the Texas Revolution. He served as the first and third president of the Republic of Texas and was one of the first two individuals to represent Texas in the United States Senate. He also served as the sixth governor of Tennessee and the seventh governor of Texas, the only individual to be elected governor of two different states in the United States.

Week 28: Wed., May. 21, 2025

The Mexican-American War

WEEK 28

The Mexican–American War was an invasion of Mexico by the United States Army from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1845 American annexation of Texas, which Mexico still considered its territory because Mexico refused to recognize the Treaties of Velasco, signed by President Antonio López de Santa Anna after he was captured by the Texian Army during the 1836 Texas Revolution. The Republic of Texas was de facto an independent country, but most of its Anglo-American citizens who had moved from the United States to Texas after 1822 wanted to be annexed by the United States. In the United States, sectional politics over slavery had previously prevented annexation because Texas, formerly a slavery-free territory under Mexican rule, would have been admitted as a slave state, upsetting the balance of power between Northern free states and Southern slave states. In the 1844 United States presidential election, Democrat James K. Polk was elected on a platform of expanding U.S. territory to Oregon, California, and Texas by any means, with the 1845 annexation of Texas furthering that goal.

Week 29: Wed., May. 28, 2025

California 1849

WEEK 29

Prior to European colonization, California was one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse areas in pre-Columbian North America. European exploration in the 16th and 17th centuries led to the colonization by the Spanish Empire. The area became a part of Mexico in 1821, following its successful war for independence, but was ceded to the United States in 1848 after the Mexican–American War. The California Gold Rush started in 1848 and led to social and demographic changes. The western portion of Alta California was then organized and admitted as the 31st state in 1850, as a free state, following the Compromise of 1850.

Week 30: Wed., Jun. 4, 2025

The Western

WEEK 30

The Western

BRUCE THOMPSON (UCSC)

The open range for cattle drives lasted less than a quarter of a century after the Civil War, and the last major Indian war ended in 1890 with the defeat of the Sioux at Wounded Knee. In 1890, the US Census Bureau announced the closing of the frontier. Yet for more than half of the century that followed, the Western was one of the pillars of American popular culture, first on the stage (Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show, in literature (starting with Owen Wister’s The Virginian, 1902), cinema (starting with Cecil B. DeMille’s The Squaw Man in 1914), and on television (Westerns were the dominant genre through the first half of the 1960s). How do we account for this extraordinarily long and rich afterlife of the frontier in American popular culture? Why did so many of the finest and most influential American directors (John Ford, Howard Hawks, Anthony Mann, George Stevens) and actors (Gary Cooper, John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, Henry Fonda, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, Robert Ryan, Glenn Ford, Van Heflin, Clint Eastwood) do so much of their best work in this genre? What exactly was "the Western," and how did it evolve? A preliminary answer: the Western offered attractive versions of heroism, placed within a historical context that seemed to evoke something essential about our "national character." The great popularity of the genre, writes Forrest Robinson in his book Having It Both Ways: Self-subversion in Western Popular Classics, "is quite obviously the result of this emphasis on the heroic, with its abundance of vigorous action in colorful settings, and its attention to such values as courage, independence, self-reliance, and the stoical indifference to pain." But having established these values as central to our national self-image, the writers and film directors who developed the canon of Western literature and cinema then proceeded to complicate them: revising the stereotypes, and sometimes subverting them. And sometimes, as in the books of Elmore Leonard and Cormac McCarthy, and the films of Ford, Hawks, Mann, and Stevens, they have produced works of art that both celebrate and criticize our culture at the same time.

RECOMMENDED READING

Renowned storyteller Dee Brown, author of the bestselling Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, recreates the struggles of Native Americans, settlers, and ranchers in this stunning volume that illuminates the history of the old West that’s filled with maps and vintage photographs. Beginning with the demise of the Native Americans of the Plains, Brown depicts the onrush of the burgeoning cattle trade and the waves of immigrants who ultimately “settled” the land. In the retelling of this oft-told saga, Brown has demonstrated once again his abilities as a master storyteller and an entertaining popular historian. By turns heroic, tragic, and even humorous, The American West brings to life American tragedy and triumph in the years from 1840 to the turn of the century, and a roster of characters both great and small: Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, Geronimo, Dull Knife, Crazy Horse, Captain Jack, John H. Tunstall, Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett, Wyatt Earp, the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang, Wild Bill Hickok, Charles Goodnight, Oliver Loving, Buffalo Bill, and many others.