Week 1

Week 1: Tuesday, October 3, 2017

When Did the Renaissance End and When Did Something New Take its Place?

We are beginning our studies this Fall Quarter at about the year 1600. Therefore we are jumping in to Western Civilization after more than 4500 years of preceding events. Especially challenging, will be relating our studies last year on the Renaissance to this year's studies on Modern Italy. Where does the Renaissance end and where does "Modern" begin? Or a better question: Is the Renaissance itself the beginning of the Modern world? Or was the Renaissance really modern, or was it just the tail end of the whole Medieval Transition from the Ancient to the Modern? Historians have never agreed on this question. Whole schools of history see the Renaissance as old fashioned and stuck in the past. They say that nothing really new emerged until after 1600. But then what do we do with Leonardo da Vinci or Christopher Columbus or Copernicus? Certainly they were all part of Modernity, and at the same time pure Renaissance men. So it seems all the rules and regulations about periods and dates get very troubling when we come to the question of the end of the Renaissance and the thing we called Modernity. These are the questions we should use our first night to discuss.

1. What was the Renaissance; where did it begin?

2. When did the Renaissance end? Or did it ever end?

3. When did European culture stop being Renaissance and start being something else?

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

RECOMMENDED READING:

Here are two books that we used last year in our Renaissance Class that some of you may find helpful in these first weeks.

J. R. Hale, The Civilization of Europe in the Renaissance. This study of the whole Renaissance period in all of Europe was the final masterpiece of one of the greatest historians of the Early Modern period. John Hale was working on this book when he suffered a debilitating stroke. But his wife, Sheila Hale, and other scholars finished the book for publication and we are all enriched by its availability. It is in print, but you might also look at used copies of the original quality paperback. This book will serve us for the whole year-long course. It is especially useful for Winter and Spring Quarters.

John Hale,

The Civilization of Europe in the Renaissance,

Scribner, Reprint edition (June 1, 1995),

ISBN 0684803526

RECOMMENDED READING:

This is a beautiful book which covers the whole of the Renaissance in every field and every country. Margaret King is one of the greatest American scholars of the Renaissance, and she has written a very useful general book on the subject. What is especially attractive, is all the extra material: the charts, the maps, the photos, all of which make this a great study of the Renaissance. It would be a useful "textbook" for our whole year on the Renaissance. It was, of course, designed as a college textbook for a course on the Renaissance. If you buy a new copy, it is 35$ but there are many used copies listed on Amazon.

Margaret L. King, is Professor Emerita of history at Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York. She is the author of several books on women, humanism, and Venice in the Renaissance, and is currently editor-in-chief of the Renaissance and Reformation online bibliography published by Oxford Bibliographies.

Margaret L. King,

The Renaissance in Europe,

Laurence King Publishing; 2 edition (January 1, 2003),

ISBN 1856693740

2

Week 2: Tuesday, October 10, 2017

Was Italy Still a Dynamic and Creative Culture in the 17th Century?

If we decide that the Italian Renaissance came to an end somewhere during the Seventeenth Century, then the question is: was the new Italy of the 1600s still alive and well and creative as it had been during the days of Lorenzo de' Medici and Leonardo da Vinci? To answer this question we need only recite the names of some of the most creative Italians of the Seventeenth Century: Galileo, Caravaggio, Bernini, Boromini, the Gentileschis, Vivaldi, and many more. But now after 1600, Italy found herself in competition with other European nations that were striding ahead with equal or greater energies than those of Italy. Now in the 1600s for the first time since Dante, Italy was falling behind. Why?

If we decide that the Italian Renaissance came to an end somewhere during the Seventeenth Century, then the question is: was the new Italy of the 1600s still alive and well and creative as it had been during the days of Lorenzo de' Medici and Leonardo da Vinci? To answer this question we need only recite the names of some of the most creative Italians of the Seventeenth Century: Galileo, Caravaggio, Bernini, Boromini, the Gentileschis, Vivaldi, and many more. But now after 1600, Italy found herself in competition with other European nations that were striding ahead with equal or greater energies than those of Italy. Now in the 1600s for the first time since Dante, Italy was falling behind. Why?

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

3

Week 3: Tuesday, October 17, 2017

Caravaggio in Rome

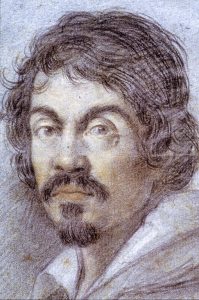

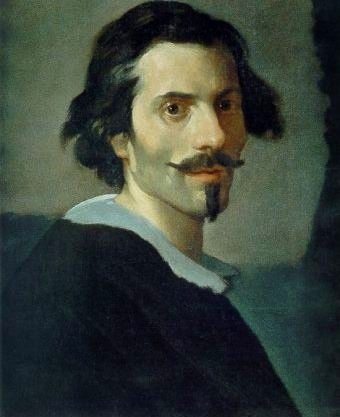

The portrait you see on the left is a portrait of Caravaggio. Michelangelo da Merisi, always known for his hometown in northern Italy, was one of the most revolutionary artists who ever lived. We would have to search through the art of the West up to the time of Picasso to find any other artist with such immediate impact. By 1650, everyone admitted that they all were "Caravagisti." that is, followers of Caravaggio. Giotto, Caravaggio, and Picasso mark revolutionary breaks with what had gone before. His greatest years of creativity are lived in Rome -- the great Rome that was exploding in the 17th century. The Rome of the Counter Reformation, the Rome of the growing international Roman Catholic Church was at its peak of creativity and energy in the first half of the Seventeenth Century. And no one symbolized better the powerful influence of Rome than did Caravaggio. A friend of Popes and Bishops, a friend of Dukes and Duchesses, he was always in trouble.

The portrait you see on the left is a portrait of Caravaggio. Michelangelo da Merisi, always known for his hometown in northern Italy, was one of the most revolutionary artists who ever lived. We would have to search through the art of the West up to the time of Picasso to find any other artist with such immediate impact. By 1650, everyone admitted that they all were "Caravagisti." that is, followers of Caravaggio. Giotto, Caravaggio, and Picasso mark revolutionary breaks with what had gone before. His greatest years of creativity are lived in Rome -- the great Rome that was exploding in the 17th century. The Rome of the Counter Reformation, the Rome of the growing international Roman Catholic Church was at its peak of creativity and energy in the first half of the Seventeenth Century. And no one symbolized better the powerful influence of Rome than did Caravaggio. A friend of Popes and Bishops, a friend of Dukes and Duchesses, he was always in trouble.

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

RECOMMENDED BOOK:

Andrew Graham-Dixon,

Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane,

W. W. Norton & Company; 1 edition (November 12, 2012),

ISBN 9780393343434

4

Week 4: Tuesday, October 24, 2017

Bernini in Rome

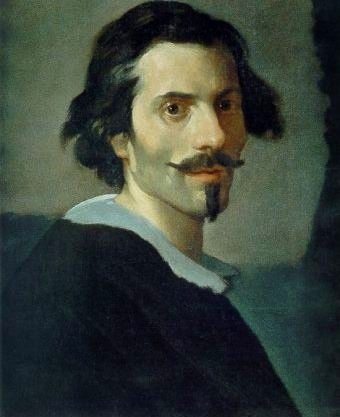

The extraordinary man at the right was the most successful Italian artist of the seventeenth century. As one scholar has commented, "What Shakespeare is to drama, Bernini may be to sculpture: the first pan-European sculptor whose name is instantaneously identifiable with a particular manner and vision, and whose influence was inordinately powerful…." He was both a great architect and a great sculptor–the greatest sculptor since Michelangelo. He was born in Naples, but lived most of his incredible 82 years in Rome. And it would be impossible to appreciate his work without a trip to Rome.

The extraordinary man at the right was the most successful Italian artist of the seventeenth century. As one scholar has commented, "What Shakespeare is to drama, Bernini may be to sculpture: the first pan-European sculptor whose name is instantaneously identifiable with a particular manner and vision, and whose influence was inordinately powerful…." He was both a great architect and a great sculptor–the greatest sculptor since Michelangelo. He was born in Naples, but lived most of his incredible 82 years in Rome. And it would be impossible to appreciate his work without a trip to Rome.

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

NO CLASS NEXT WEEK THANKSGIVING VACATION

5

Week 5: Tuesday, October 31, 2017

The Rome of Pope Urban VIII

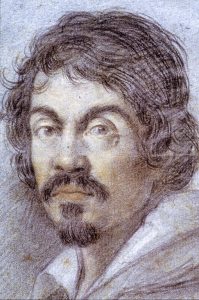

The dynamic portrait at the left is of Maffeo Barberini when he was still a bishop. Later he would be Pope Urban VIII. The portrait is by his good friend Caravaggio. The painter traveled among the most powerful men in Rome during his early years in the capital and Maffeo Barberini was one of the most powerful. Pope Urban VIII, 1568 –1644, reigned as Pope from 6 August 1623 to his death in 1644. He expanded the papal territory by force of arms and advantageous politicking, and was also a prominent patron of the arts and a reformer of Church missions. Barberini was a Florentine from an old noble family. He was given an excellent education and rose quickly within the church. HIs papacy of 21 years was unusually long and therefore the two decades gave him time to make a major impact on both the city of Rome and the international church.

The dynamic portrait at the left is of Maffeo Barberini when he was still a bishop. Later he would be Pope Urban VIII. The portrait is by his good friend Caravaggio. The painter traveled among the most powerful men in Rome during his early years in the capital and Maffeo Barberini was one of the most powerful. Pope Urban VIII, 1568 –1644, reigned as Pope from 6 August 1623 to his death in 1644. He expanded the papal territory by force of arms and advantageous politicking, and was also a prominent patron of the arts and a reformer of Church missions. Barberini was a Florentine from an old noble family. He was given an excellent education and rose quickly within the church. HIs papacy of 21 years was unusually long and therefore the two decades gave him time to make a major impact on both the city of Rome and the international church.

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

6

Week 6: Tuesday, November 7, 2017

Pope Urban VIII versus Galileo

In 1633, a twenty-three year old intellectual dispute exploded into the most famous trial for heresy of the time. The process was not desired by any of the parties. Pope Urban was an old school friend of Galileo. He was an intellectual with an extraordinary education. He knew most of the books that had fed Galileo in his ideas. Galileo also did not want any confrontation with the church. And he thought he had obeyed all the rules that had been laid down in his previous confrontation with the church. Even since 1610, when he published The Starry Messenger he had been engaged in a huge debate about the nature of the universe. HIs book with its revolutionary observations using the new telescope contained data that strengthened the Copernican theory about the heliocentric universe. Galileo. of course. agreed with Copernicus. And he knew that his book would stoke the fires of controversy. But only slowly did the debate grow into a major controversy that swept up all the different faculties in the universities. By 1633, the now long running debate reached an explosion when Galileo published another book Dialogue on Two World Systemsin which he added more information to the debate. His old friend the Pope could no longer stand aside and both men were drawn into the life and death struggle. At this moment Rome was at the center of the huge debate, a debate that had been going on for 100 years. But now with all the new data that Galileo had provided, more and more scientists were beginning to agree with Copernicus.

In 1633, a twenty-three year old intellectual dispute exploded into the most famous trial for heresy of the time. The process was not desired by any of the parties. Pope Urban was an old school friend of Galileo. He was an intellectual with an extraordinary education. He knew most of the books that had fed Galileo in his ideas. Galileo also did not want any confrontation with the church. And he thought he had obeyed all the rules that had been laid down in his previous confrontation with the church. Even since 1610, when he published The Starry Messenger he had been engaged in a huge debate about the nature of the universe. HIs book with its revolutionary observations using the new telescope contained data that strengthened the Copernican theory about the heliocentric universe. Galileo. of course. agreed with Copernicus. And he knew that his book would stoke the fires of controversy. But only slowly did the debate grow into a major controversy that swept up all the different faculties in the universities. By 1633, the now long running debate reached an explosion when Galileo published another book Dialogue on Two World Systemsin which he added more information to the debate. His old friend the Pope could no longer stand aside and both men were drawn into the life and death struggle. At this moment Rome was at the center of the huge debate, a debate that had been going on for 100 years. But now with all the new data that Galileo had provided, more and more scientists were beginning to agree with Copernicus.

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED READING

I highly recommend this wonderful book to you and am delighted that it is now available in a paperback edition. It is a book that will capture your heart as you read of Galileo's extraordinary daughter Suor Maria Celeste and read her touching letters to her beloved father. We will visit her monastery on our Galileo night, so it will be a great night with beautiful pictures of the hills south of Florence where Galileo and his daughter lived their lives.

7

Week 7: Tuesday, November 14, 2017

Artemisia Gentileschi in Rome

NO MEETING NEXT WEEK NOV 21

THANKSGIVING VACATION

The career of Artemisia Gentileschi (see her self-portrait at the left) is testimony to how creative and energetic the cultural world of seventeenth-century Rome was. Artemisia was the first independent and successful woman painter of the modern world. Her art survives to tell us just how great a painter she was. But there is more. She was also an extraordinary woman who dared to take a man to court who raped her. And we know all about it. All the documents have survived. Thus we have an amazing look into the world of Italian justice in the seventeenth century. Artemisia was a great painter, a "Caravagisti" who grew up in the very neighborhood where Caravaggio had lived. But she is also a fascinating woman.

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

RECOMMENDED BOOK:

Keith Christiansen,

Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi,

Metropolitan Museum of Art; First Edition edition (December 1, 2001),

ISBN 0300090773

From Library Journal

This book, which accompanies an exhibition currently at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and traveling both to the St. Louis Art Museum and to the Museo di Palazzo di Venezia in Rome, is the first to examine in one volume both Orazio and Artemesia Gentileschi, father-and-daughter artists of 17th-century Italy. The catalog demonstrates that Orazio Gentileschi follows the Caravaggesque practice of painting from the model, which Artemesia in turn absorbed into her own painting methods. At the same time, curator Christiansen concludes that Orazio painted much more in the elegant style of classical painting in France and never accepted the Baroque idioms of drama and expressiveness that his daughter Artemesia wholeheartedly embraced in her painting. Also discussed in this catalog is the feminist aspect of Artemesia's position as a talented woman artist, the possibility that she was the model for her own "Susanna and the Elders" early in her career, and how her social environment and opportunities as a woman artist changed dramatically after her marriage and her move from Rome to Florence. This catalog also includes excellent color reproductions and previously unpublished documents relating to the trial of Orazio's colleague, Agostino Tassi, for raping Artemesia. The scholarly literature on these artists should be advanced considerably by this extremely comprehensive volume. Enthusiastically recommended for all libraries that support programs in art and art history. [Interested readers will also want to look at Susan Vreeland's The Passion of Artemisia, a fictional account of the artists reviewed in LJ 12/01. Ed.] Sandra Rothenberg, Framingham State Coll., MA

Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information, Inc.

8

Week 8: Tuesday, November 28, 2017

Music in Venice

Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) was an Italian composer, gambist, and singer. Monteverdi's work, often regarded as revolutionary, marked the change from the Renaissance style of music to that of the Baroque period. He developed two styles of composition – the heritage of Renaissance polyphony and the new basso continuo technique of the Baroque. Monteverdi wrote one of the earliest operas, L'Orfeo, a novel work that is the earliest surviving opera still regularly performed. He is widely recognized as an inventive composer who enjoyed considerable fame in his lifetime.

Venice was the international center of a musical revolution in the seventeenth century. Composers like Monteverdi created a whole new art form: Opera.

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

9

Week 9: Tuesday, December 5, 2017

The Last Medici

Anna Maria Luisa de' Medici, 1667-1743 was the last Medici in Florence. At the end of her life she decided to donate the family's collection of art to the nation and to the public of the whole world. This act yielded one of the greatest treasures of art ever assembled. And it is all still in the same rooms of the palace where the great works of art have hung for more than 500 years

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

RECOMMENDED BOOK:

Harold Acton,

The Last Medici,

Thames & Hudson; 1st edition (September 1980),

ISBN 050025074X

In his remarkable account of the last Medici, historian Harold Acton (1904-1994) takes up the causes which led to the disappearance of a house which has left indelible traces on the art, literature and commerce of the world; and his book was one of the first attempts to deal with this despotic dynasty in a scholarly and impartial spirit. Much has been written about the phenomenal career of the early Medici: and there are many biographies of Lorenzo the Magnificent, Cosimo I, and the Medicean Popes. But less has been written of the final phase, and Acton demonstrates the hand of death overshadowing the great family in a series of unfortunate marriages - how one by one they vanished into the void. "The Last Medici" centres mainly round the fantastic figures of Princess Marguerite-Louise d'Orleans and her husband Cosimo III, most fatal of all the Medicean sovereigns. The last act closes on Gian Gastone, their cynical younger son, bedridden in the Pitti Palace, a florid figure of despair, with the Powers of Europe ever on the alert for the sound of his death-rattle. Full of brilliant colour, rich comedy and lurid tragedy.

10

Week 10: Tuesday, December 12, 2017

Europe in Crisis: 1700

The picture you see at the top of the page is the magnificent memorial to the Surrender of Breda in 1635 painted by Velazquez. The scene and the painting marked the slow end to the almost eighty-year war of Dutch Independence. This treaty was the beginning of peace and the final acceptance by Catholic Europe that the Protestant Dutch were going to have their own country and there was no point in fighting any longer. The southern provinces (Flanders, Brabant) would remain Roman Catholic, the northern provinces would become the new Protestant United Provinces (Holland etc). Thus began a relatively peaceful later 17th century. Holland prospered. Amsterdam exploded into phenomenal growth and prosperity. But as Europe looked toward 1700, all political leaders worried about the Spanish Royal family and the fragile health of King Charles II (portrait at left). Charles had no heirs and there was no likelihood that any wold appear. Charles was sick and wasting away. The death of the King of Spain with no legitimate heir meant that the Spanish throne would pass to other heirs in either France (unacceptable to England and Holland) or Vienna (the German branch of the Habsburgs). Either choice would inevitably spark a war. And so as 1700 approached, all of the European governments watched the health reports on King Charles II in Madrid. On November 1, 1700, King Charles II of Spain died.

The picture you see at the top of the page is the magnificent memorial to the Surrender of Breda in 1635 painted by Velazquez. The scene and the painting marked the slow end to the almost eighty-year war of Dutch Independence. This treaty was the beginning of peace and the final acceptance by Catholic Europe that the Protestant Dutch were going to have their own country and there was no point in fighting any longer. The southern provinces (Flanders, Brabant) would remain Roman Catholic, the northern provinces would become the new Protestant United Provinces (Holland etc). Thus began a relatively peaceful later 17th century. Holland prospered. Amsterdam exploded into phenomenal growth and prosperity. But as Europe looked toward 1700, all political leaders worried about the Spanish Royal family and the fragile health of King Charles II (portrait at left). Charles had no heirs and there was no likelihood that any wold appear. Charles was sick and wasting away. The death of the King of Spain with no legitimate heir meant that the Spanish throne would pass to other heirs in either France (unacceptable to England and Holland) or Vienna (the German branch of the Habsburgs). Either choice would inevitably spark a war. And so as 1700 approached, all of the European governments watched the health reports on King Charles II in Madrid. On November 1, 1700, King Charles II of Spain died.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

All

Week 1: Tue., Oct. 3, 2017

When Did the Renaissance End and When Did Something New Take its Place?

We are beginning our studies this Fall Quarter at about the year 1600. Therefore we are jumping in to Western Civilization after more than 4500 years of preceding events. Especially challenging, will be relating our studies last year on the Renaissance to this year's studies on Modern Italy. Where does the Renaissance end and where does "Modern" begin? Or a better question: Is the Renaissance itself the beginning of the Modern world? Or was the Renaissance really modern, or was it just the tail end of the whole Medieval Transition from the Ancient to the Modern? Historians have never agreed on this question. Whole schools of history see the Renaissance as old fashioned and stuck in the past. They say that nothing really new emerged until after 1600. But then what do we do with Leonardo da Vinci or Christopher Columbus or Copernicus? Certainly they were all part of Modernity, and at the same time pure Renaissance men. So it seems all the rules and regulations about periods and dates get very troubling when we come to the question of the end of the Renaissance and the thing we called Modernity. These are the questions we should use our first night to discuss.

1. What was the Renaissance; where did it begin?

2. When did the Renaissance end? Or did it ever end?

3. When did European culture stop being Renaissance and start being something else?

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

RECOMMENDED READING:

Here are two books that we used last year in our Renaissance Class that some of you may find helpful in these first weeks.

J. R. Hale, The Civilization of Europe in the Renaissance. This study of the whole Renaissance period in all of Europe was the final masterpiece of one of the greatest historians of the Early Modern period. John Hale was working on this book when he suffered a debilitating stroke. But his wife, Sheila Hale, and other scholars finished the book for publication and we are all enriched by its availability. It is in print, but you might also look at used copies of the original quality paperback. This book will serve us for the whole year-long course. It is especially useful for Winter and Spring Quarters.

John Hale,

The Civilization of Europe in the Renaissance,

Scribner, Reprint edition (June 1, 1995),

ISBN 0684803526

RECOMMENDED READING:

This is a beautiful book which covers the whole of the Renaissance in every field and every country. Margaret King is one of the greatest American scholars of the Renaissance, and she has written a very useful general book on the subject. What is especially attractive, is all the extra material: the charts, the maps, the photos, all of which make this a great study of the Renaissance. It would be a useful "textbook" for our whole year on the Renaissance. It was, of course, designed as a college textbook for a course on the Renaissance. If you buy a new copy, it is 35$ but there are many used copies listed on Amazon.

Margaret L. King, is Professor Emerita of history at Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York. She is the author of several books on women, humanism, and Venice in the Renaissance, and is currently editor-in-chief of the Renaissance and Reformation online bibliography published by Oxford Bibliographies.

Margaret L. King,

The Renaissance in Europe,

Laurence King Publishing; 2 edition (January 1, 2003),

ISBN 1856693740

Week 2: Tue., Oct. 10, 2017

Was Italy Still a Dynamic and Creative Culture in the 17th Century?

If we decide that the Italian Renaissance came to an end somewhere during the Seventeenth Century, then the question is: was the new Italy of the 1600s still alive and well and creative as it had been during the days of Lorenzo de' Medici and Leonardo da Vinci? To answer this question we need only recite the names of some of the most creative Italians of the Seventeenth Century: Galileo, Caravaggio, Bernini, Boromini, the Gentileschis, Vivaldi, and many more. But now after 1600, Italy found herself in competition with other European nations that were striding ahead with equal or greater energies than those of Italy. Now in the 1600s for the first time since Dante, Italy was falling behind. Why?

If we decide that the Italian Renaissance came to an end somewhere during the Seventeenth Century, then the question is: was the new Italy of the 1600s still alive and well and creative as it had been during the days of Lorenzo de' Medici and Leonardo da Vinci? To answer this question we need only recite the names of some of the most creative Italians of the Seventeenth Century: Galileo, Caravaggio, Bernini, Boromini, the Gentileschis, Vivaldi, and many more. But now after 1600, Italy found herself in competition with other European nations that were striding ahead with equal or greater energies than those of Italy. Now in the 1600s for the first time since Dante, Italy was falling behind. Why?

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

Week 3: Tue., Oct. 17, 2017

Caravaggio in Rome

The portrait you see on the left is a portrait of Caravaggio. Michelangelo da Merisi, always known for his hometown in northern Italy, was one of the most revolutionary artists who ever lived. We would have to search through the art of the West up to the time of Picasso to find any other artist with such immediate impact. By 1650, everyone admitted that they all were "Caravagisti." that is, followers of Caravaggio. Giotto, Caravaggio, and Picasso mark revolutionary breaks with what had gone before. His greatest years of creativity are lived in Rome -- the great Rome that was exploding in the 17th century. The Rome of the Counter Reformation, the Rome of the growing international Roman Catholic Church was at its peak of creativity and energy in the first half of the Seventeenth Century. And no one symbolized better the powerful influence of Rome than did Caravaggio. A friend of Popes and Bishops, a friend of Dukes and Duchesses, he was always in trouble.

The portrait you see on the left is a portrait of Caravaggio. Michelangelo da Merisi, always known for his hometown in northern Italy, was one of the most revolutionary artists who ever lived. We would have to search through the art of the West up to the time of Picasso to find any other artist with such immediate impact. By 1650, everyone admitted that they all were "Caravagisti." that is, followers of Caravaggio. Giotto, Caravaggio, and Picasso mark revolutionary breaks with what had gone before. His greatest years of creativity are lived in Rome -- the great Rome that was exploding in the 17th century. The Rome of the Counter Reformation, the Rome of the growing international Roman Catholic Church was at its peak of creativity and energy in the first half of the Seventeenth Century. And no one symbolized better the powerful influence of Rome than did Caravaggio. A friend of Popes and Bishops, a friend of Dukes and Duchesses, he was always in trouble.

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

RECOMMENDED BOOK:

Andrew Graham-Dixon,

Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane,

W. W. Norton & Company; 1 edition (November 12, 2012),

ISBN 9780393343434

Week 4: Tue., Oct. 24, 2017

Bernini in Rome

The extraordinary man at the right was the most successful Italian artist of the seventeenth century. As one scholar has commented, "What Shakespeare is to drama, Bernini may be to sculpture: the first pan-European sculptor whose name is instantaneously identifiable with a particular manner and vision, and whose influence was inordinately powerful…." He was both a great architect and a great sculptor–the greatest sculptor since Michelangelo. He was born in Naples, but lived most of his incredible 82 years in Rome. And it would be impossible to appreciate his work without a trip to Rome.

The extraordinary man at the right was the most successful Italian artist of the seventeenth century. As one scholar has commented, "What Shakespeare is to drama, Bernini may be to sculpture: the first pan-European sculptor whose name is instantaneously identifiable with a particular manner and vision, and whose influence was inordinately powerful…." He was both a great architect and a great sculptor–the greatest sculptor since Michelangelo. He was born in Naples, but lived most of his incredible 82 years in Rome. And it would be impossible to appreciate his work without a trip to Rome.

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

NO CLASS NEXT WEEK THANKSGIVING VACATION

Week 5: Tue., Oct. 31, 2017

The Rome of Pope Urban VIII

The dynamic portrait at the left is of Maffeo Barberini when he was still a bishop. Later he would be Pope Urban VIII. The portrait is by his good friend Caravaggio. The painter traveled among the most powerful men in Rome during his early years in the capital and Maffeo Barberini was one of the most powerful. Pope Urban VIII, 1568 –1644, reigned as Pope from 6 August 1623 to his death in 1644. He expanded the papal territory by force of arms and advantageous politicking, and was also a prominent patron of the arts and a reformer of Church missions. Barberini was a Florentine from an old noble family. He was given an excellent education and rose quickly within the church. HIs papacy of 21 years was unusually long and therefore the two decades gave him time to make a major impact on both the city of Rome and the international church.

The dynamic portrait at the left is of Maffeo Barberini when he was still a bishop. Later he would be Pope Urban VIII. The portrait is by his good friend Caravaggio. The painter traveled among the most powerful men in Rome during his early years in the capital and Maffeo Barberini was one of the most powerful. Pope Urban VIII, 1568 –1644, reigned as Pope from 6 August 1623 to his death in 1644. He expanded the papal territory by force of arms and advantageous politicking, and was also a prominent patron of the arts and a reformer of Church missions. Barberini was a Florentine from an old noble family. He was given an excellent education and rose quickly within the church. HIs papacy of 21 years was unusually long and therefore the two decades gave him time to make a major impact on both the city of Rome and the international church.

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

Week 6: Tue., Nov. 7, 2017

Pope Urban VIII versus Galileo

In 1633, a twenty-three year old intellectual dispute exploded into the most famous trial for heresy of the time. The process was not desired by any of the parties. Pope Urban was an old school friend of Galileo. He was an intellectual with an extraordinary education. He knew most of the books that had fed Galileo in his ideas. Galileo also did not want any confrontation with the church. And he thought he had obeyed all the rules that had been laid down in his previous confrontation with the church. Even since 1610, when he published The Starry Messenger he had been engaged in a huge debate about the nature of the universe. HIs book with its revolutionary observations using the new telescope contained data that strengthened the Copernican theory about the heliocentric universe. Galileo. of course. agreed with Copernicus. And he knew that his book would stoke the fires of controversy. But only slowly did the debate grow into a major controversy that swept up all the different faculties in the universities. By 1633, the now long running debate reached an explosion when Galileo published another book Dialogue on Two World Systemsin which he added more information to the debate. His old friend the Pope could no longer stand aside and both men were drawn into the life and death struggle. At this moment Rome was at the center of the huge debate, a debate that had been going on for 100 years. But now with all the new data that Galileo had provided, more and more scientists were beginning to agree with Copernicus.

In 1633, a twenty-three year old intellectual dispute exploded into the most famous trial for heresy of the time. The process was not desired by any of the parties. Pope Urban was an old school friend of Galileo. He was an intellectual with an extraordinary education. He knew most of the books that had fed Galileo in his ideas. Galileo also did not want any confrontation with the church. And he thought he had obeyed all the rules that had been laid down in his previous confrontation with the church. Even since 1610, when he published The Starry Messenger he had been engaged in a huge debate about the nature of the universe. HIs book with its revolutionary observations using the new telescope contained data that strengthened the Copernican theory about the heliocentric universe. Galileo. of course. agreed with Copernicus. And he knew that his book would stoke the fires of controversy. But only slowly did the debate grow into a major controversy that swept up all the different faculties in the universities. By 1633, the now long running debate reached an explosion when Galileo published another book Dialogue on Two World Systemsin which he added more information to the debate. His old friend the Pope could no longer stand aside and both men were drawn into the life and death struggle. At this moment Rome was at the center of the huge debate, a debate that had been going on for 100 years. But now with all the new data that Galileo had provided, more and more scientists were beginning to agree with Copernicus.

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED READING

I highly recommend this wonderful book to you and am delighted that it is now available in a paperback edition. It is a book that will capture your heart as you read of Galileo's extraordinary daughter Suor Maria Celeste and read her touching letters to her beloved father. We will visit her monastery on our Galileo night, so it will be a great night with beautiful pictures of the hills south of Florence where Galileo and his daughter lived their lives.

Week 7: Tue., Nov. 14, 2017

Artemisia Gentileschi in Rome

NO MEETING NEXT WEEK NOV 21

THANKSGIVING VACATION

The career of Artemisia Gentileschi (see her self-portrait at the left) is testimony to how creative and energetic the cultural world of seventeenth-century Rome was. Artemisia was the first independent and successful woman painter of the modern world. Her art survives to tell us just how great a painter she was. But there is more. She was also an extraordinary woman who dared to take a man to court who raped her. And we know all about it. All the documents have survived. Thus we have an amazing look into the world of Italian justice in the seventeenth century. Artemisia was a great painter, a "Caravagisti" who grew up in the very neighborhood where Caravaggio had lived. But she is also a fascinating woman.

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

RECOMMENDED BOOK:

Keith Christiansen,

Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi,

Metropolitan Museum of Art; First Edition edition (December 1, 2001),

ISBN 0300090773

From Library Journal

This book, which accompanies an exhibition currently at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and traveling both to the St. Louis Art Museum and to the Museo di Palazzo di Venezia in Rome, is the first to examine in one volume both Orazio and Artemesia Gentileschi, father-and-daughter artists of 17th-century Italy. The catalog demonstrates that Orazio Gentileschi follows the Caravaggesque practice of painting from the model, which Artemesia in turn absorbed into her own painting methods. At the same time, curator Christiansen concludes that Orazio painted much more in the elegant style of classical painting in France and never accepted the Baroque idioms of drama and expressiveness that his daughter Artemesia wholeheartedly embraced in her painting. Also discussed in this catalog is the feminist aspect of Artemesia's position as a talented woman artist, the possibility that she was the model for her own "Susanna and the Elders" early in her career, and how her social environment and opportunities as a woman artist changed dramatically after her marriage and her move from Rome to Florence. This catalog also includes excellent color reproductions and previously unpublished documents relating to the trial of Orazio's colleague, Agostino Tassi, for raping Artemesia. The scholarly literature on these artists should be advanced considerably by this extremely comprehensive volume. Enthusiastically recommended for all libraries that support programs in art and art history. [Interested readers will also want to look at Susan Vreeland's The Passion of Artemisia, a fictional account of the artists reviewed in LJ 12/01. Ed.] Sandra Rothenberg, Framingham State Coll., MA

Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information, Inc.

Week 8: Tue., Nov. 28, 2017

Music in Venice

Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) was an Italian composer, gambist, and singer. Monteverdi's work, often regarded as revolutionary, marked the change from the Renaissance style of music to that of the Baroque period. He developed two styles of composition – the heritage of Renaissance polyphony and the new basso continuo technique of the Baroque. Monteverdi wrote one of the earliest operas, L'Orfeo, a novel work that is the earliest surviving opera still regularly performed. He is widely recognized as an inventive composer who enjoyed considerable fame in his lifetime.

Venice was the international center of a musical revolution in the seventeenth century. Composers like Monteverdi created a whole new art form: Opera.

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

Week 9: Tue., Dec. 5, 2017

The Last Medici

Anna Maria Luisa de' Medici, 1667-1743 was the last Medici in Florence. At the end of her life she decided to donate the family's collection of art to the nation and to the public of the whole world. This act yielded one of the greatest treasures of art ever assembled. And it is all still in the same rooms of the palace where the great works of art have hung for more than 500 years

REQUIRED READING:

This is the best one-volume history of Italy that includes the modern part that we want. It provides you with a nice introduction to earlier periods and those of you who studied the Renaissance last year will find these chapters an easy review. You can read about the earlier periods a bit each week tip you get up to 1600. We will use the book all year.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430

RECOMMENDED BOOK:

Harold Acton,

The Last Medici,

Thames & Hudson; 1st edition (September 1980),

ISBN 050025074X

In his remarkable account of the last Medici, historian Harold Acton (1904-1994) takes up the causes which led to the disappearance of a house which has left indelible traces on the art, literature and commerce of the world; and his book was one of the first attempts to deal with this despotic dynasty in a scholarly and impartial spirit. Much has been written about the phenomenal career of the early Medici: and there are many biographies of Lorenzo the Magnificent, Cosimo I, and the Medicean Popes. But less has been written of the final phase, and Acton demonstrates the hand of death overshadowing the great family in a series of unfortunate marriages - how one by one they vanished into the void. "The Last Medici" centres mainly round the fantastic figures of Princess Marguerite-Louise d'Orleans and her husband Cosimo III, most fatal of all the Medicean sovereigns. The last act closes on Gian Gastone, their cynical younger son, bedridden in the Pitti Palace, a florid figure of despair, with the Powers of Europe ever on the alert for the sound of his death-rattle. Full of brilliant colour, rich comedy and lurid tragedy.

Week 10: Tue., Dec. 12, 2017

Europe in Crisis: 1700

The picture you see at the top of the page is the magnificent memorial to the Surrender of Breda in 1635 painted by Velazquez. The scene and the painting marked the slow end to the almost eighty-year war of Dutch Independence. This treaty was the beginning of peace and the final acceptance by Catholic Europe that the Protestant Dutch were going to have their own country and there was no point in fighting any longer. The southern provinces (Flanders, Brabant) would remain Roman Catholic, the northern provinces would become the new Protestant United Provinces (Holland etc). Thus began a relatively peaceful later 17th century. Holland prospered. Amsterdam exploded into phenomenal growth and prosperity. But as Europe looked toward 1700, all political leaders worried about the Spanish Royal family and the fragile health of King Charles II (portrait at left). Charles had no heirs and there was no likelihood that any wold appear. Charles was sick and wasting away. The death of the King of Spain with no legitimate heir meant that the Spanish throne would pass to other heirs in either France (unacceptable to England and Holland) or Vienna (the German branch of the Habsburgs). Either choice would inevitably spark a war. And so as 1700 approached, all of the European governments watched the health reports on King Charles II in Madrid. On November 1, 1700, King Charles II of Spain died.

The picture you see at the top of the page is the magnificent memorial to the Surrender of Breda in 1635 painted by Velazquez. The scene and the painting marked the slow end to the almost eighty-year war of Dutch Independence. This treaty was the beginning of peace and the final acceptance by Catholic Europe that the Protestant Dutch were going to have their own country and there was no point in fighting any longer. The southern provinces (Flanders, Brabant) would remain Roman Catholic, the northern provinces would become the new Protestant United Provinces (Holland etc). Thus began a relatively peaceful later 17th century. Holland prospered. Amsterdam exploded into phenomenal growth and prosperity. But as Europe looked toward 1700, all political leaders worried about the Spanish Royal family and the fragile health of King Charles II (portrait at left). Charles had no heirs and there was no likelihood that any wold appear. Charles was sick and wasting away. The death of the King of Spain with no legitimate heir meant that the Spanish throne would pass to other heirs in either France (unacceptable to England and Holland) or Vienna (the German branch of the Habsburgs). Either choice would inevitably spark a war. And so as 1700 approached, all of the European governments watched the health reports on King Charles II in Madrid. On November 1, 1700, King Charles II of Spain died.

Christopher Duggan,

A Concise History of Italy,

Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (January 20, 2014),

ISBN 0521747430