Week 1

Week 1: Tuesday, October 8, 2024

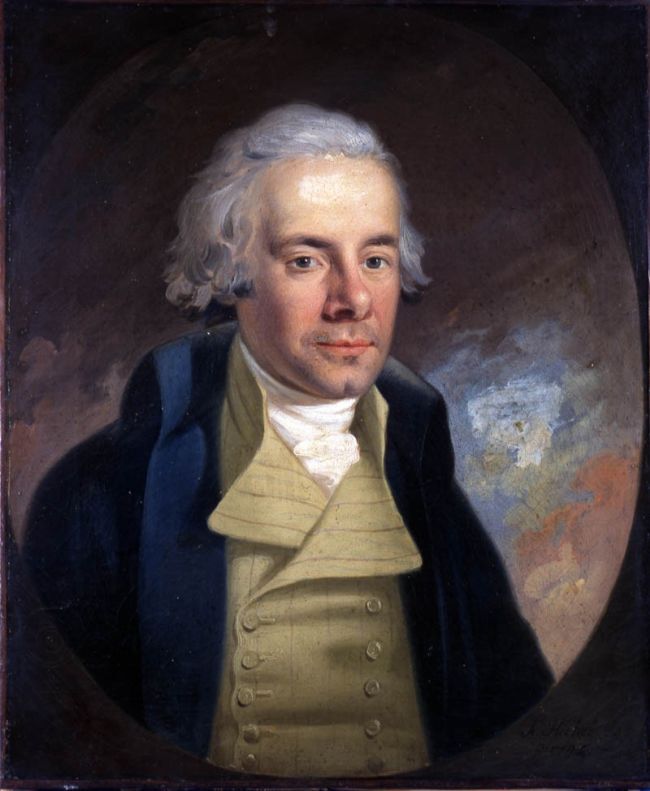

William Wilberforce

Week 1

We are beginning our 30-week journey into USA history with a look at the whole issue of slavery in the world before it came to the new US nation. First we will discuss the ubiquity of slavery in the ancient and early modern world. And then we will turn to the story of Great Britain and the one bravest man to take on the fight against slavery in all of history. William Wilberforce fought a battle in Great Britain to get it banned by the English Parliament. And he succeeded and it is one of the greatest of all stories of leadership. So we will begin with this story and then move on to the story of slavery in the USA.

Wilberforce was an English politician, philanthropist, and a leader of the movement to stop the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually becoming a Member of Parliament for Yorkshire (1784–1812). He was independent of party. In 1785, he became an evangelical Christian, which resulted in major changes to his lifestyle and a lifelong concern for social reform and progress. He was educated at St. John's College, Cambridge. In 1787, he came into contact with Thomas Clarkson and a group of anti-slave-trade activists, including Hannah More and Charles Middleton. They persuaded Wilberforce to take on the cause of abolition, and he soon became one of the leading English abolitionists. He headed the parliamentary campaign against the British slave trade for twenty years until the passage of the Slave Trade Act of 1807.

Wilberforce was an English politician, philanthropist, and a leader of the movement to stop the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually becoming a Member of Parliament for Yorkshire (1784–1812). He was independent of party. In 1785, he became an evangelical Christian, which resulted in major changes to his lifestyle and a lifelong concern for social reform and progress. He was educated at St. John's College, Cambridge. In 1787, he came into contact with Thomas Clarkson and a group of anti-slave-trade activists, including Hannah More and Charles Middleton. They persuaded Wilberforce to take on the cause of abolition, and he soon became one of the leading English abolitionists. He headed the parliamentary campaign against the British slave trade for twenty years until the passage of the Slave Trade Act of 1807.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

From the Publisher:

"For too long we’ve lacked a compact, inexpensive, authoritative, and compulsively readable book that offers American readers a clear, informative, and inspiring narrative account of their country. Such a fresh retelling of the American story is especially needed today, to shape and deepen young Americans’ sense of the land they inhabit, help them to understand its roots and share in its memories, all the while equipping them for the privileges and responsibilities of citizenship in American society. The existing texts simply fail to tell that story with energy and conviction. Too often they reflect a fragmented outlook that fails to convey to American readers the grand trajectory of their own history. A great nation needs and deserves a great and coherent narrative, as an expression of its own self-understanding and its aspirations; and it needs to be able to convey that narrative effectively. Of course, it goes without saying that such a narrative cannot be a fairy tale of the past. It will not be convincing if it is not truthful. But as Land of Hope brilliantly shows, there is no contradiction between a truthful account of the American past and an inspiring one. Readers of Land of Hope will find both in its pages."

REVIEWS

“At a time of severe partisanship that has infected many accounts of our nation’s past, this brilliant new history, Land of Hope, written in lucid and often lyrical prose, is much needed. It is accurate, honest, and free of the unhistorical condescension so often paid to the people of America’s past. This generous but not uncritical story of our nation’s history ought to be read by every American. It explains and justifies the right kind of patriotism.”― Gordon S. Wood, author of Friends Divided: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson

“We’ve long needed a readable text that truly tells the American story, neither hiding the serious injustices in our history nor soft-pedaling our nation’s extraordinary achievements. Such a text cannot be a mere compilation of facts, and it certainly could not be written by someone lacking a deep understanding and appreciation of America’s constitutional ideals and institutions. Bringing his impressive skills as a political theorist, historian, and writer to bear, Wilfred McClay has supplied the need.”― Robert P. George, McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence, Princeton University

“No one has told the story of America with greater balance or better prose than Wilfred McClay. Land of Hope is a history book that you will not be able to put down. From the moment that ‘natives’ first crossed here over the Bering Strait, to the founding of America’s great experiment in republican government, to the horror and triumph of the Civil War...McClay’s account will capture your attention while offering an unforgettable education.”― James W. Ceaser, Professor of Politics, University of Virginia

RECOMMENDED READING

Eric Metaxas,

Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the Heroic Campaign to End Slavery,

HarperOne,

ISBN 0061173886

Amazing Grace tells the story of the remarkable life of the British abolitionist William Wilberforce (1759-1833). This accessible biography chronicles Wilberforce's extraordinary role as a human rights activist, cultural reformer, and member of Parliament. At the center of this heroic life was a passionate twenty-year fight to abolish the British slave trade, a battle Wilberforce won in 1807, as well as efforts to abolish slavery itself in the British colonies, a victory achieved just three days before his death in 1833. Metaxas discovers in this unsung hero a man of whom it can truly be said: he changed the world. Before Wilberforce, few thought slavery was wrong. After Wilberforce, most societies in the world came to see it as a great moral wrong.

RECOMMENDED READING

Slavery is not and has never been a "peculiar institution," but one that is deeply rooted in the history and economy of most countries. Although it has flourished in some periods and declined in others, human bondage for profit has never been eradicated completely. In Slavery: A World History renowned author Milton Meltzer traces slavery from its origins in prehistoric hunting societies; through the boom in slave trading that reached its peak in the United States with a pre-Civil War slave population of 4,000,000; through the forced labor under the Nazi regime and in the Soviet gulags; and finally to its widespread practice in many countries today, such as the debt bondage that miners endure in Brazil or the prostitution into which women are sold in Thailand.

2

Week 2: Tuesday, October 15, 2024

Abraham Lincoln

Week 2

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

People who knew Lincoln, wrote J. G. Holland, an early biographer who interviewed dozens of associates and intimates in the months after his death, said that "he was one of the saddest men that ever lived, and that he was one of the jolliest men that ever lived; that he was very religious, but that he was not a Christian; … that he was the most cunning man in America, and that he had not a particle of cunning in him; that he had the strongest personal attachments, and that he had no personal attachments at all; … that he was a tyrant, and that he was the softest-hearted, most brotherly man that ever lived; … that he was a leader of the people, and that he was led by the people; that he was cool and impassive, and that he was susceptible of the strongest passions." It's of course a cliché to say that some great figure in our history was "a bundle of contradictions." But the fact that so many people held such different and indeed contradictory opinions about him is already suggestive of the complexity of his character

It is hardly a news flash to say that Abraham Lincoln was our greatest President. But what do we mean by "greatness"? It's a term that historians, who spend much of their time debunking reputations, are reluctant to use, because it lacks precision. But let's begin by acknowledging that Lincoln, like Churchill in the following century, (1) changed the course of history by saving a beleaguered democracy; (2) that in the dire circumstances in which he found himself in 1861, only he could have done this (again, like Churchill in 1940); and (3) that his extraordinary character as a leader depended not simply on excellence in one sphere of activity but in multiple roles, including the ability to articulate unforgettably the meaning of the struggle in which he and his people were engaged. Here, too, in his mastery of all the resources of the English language, Churchill resembled him. But there was a difference: Churchill was an aristocrat, born in a palace; Lincoln, as everybody knows, was born in a log cabin and almost entirely self-taught.

PROF. BRUCE THOMPSON

THE LINCOLN-DOUGLAS DEBATES

The most famous debates in American political history focused almost exclusively on the issue that divided Americans most bitterly and threatened the very integrity of their nation: slavery. Douglas defended his doctrine of popular sovereignty: he endorsed the decision of the citizens of Illinois to abolish slavery in their own state, but argued that what the people of other states and territories decided to do about slavery was their own business. He accused Lincoln, no longer a Whig, of being a "black Republican" who placed the interests of black slaves and his own political aspirations above the integrity of the Union. He backed Lincoln into a corner and forced him to declare himself in some respects at least a white supremacist. Lincoln fought back by attacking not only Douglas's doctrine of popular sovereignty but also the Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision of the previous year, which stated that no black person could be a citizen, that owning slaves was an inviolable right of property, and that the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and the Missouri Compromise of 1820 had violated the Fifth Amendment's prohibition against taking property without due process. If slave ownership was a constitutionally protected property right, how could territorial settlers legally exclude slavery? The Court, he said, had watered down Douglas's popular sovereignty doctrine until it was "as thin as the homeopathic soup that was made by boiling the shadow of a pigeon that had starved to death." Douglas replied that the people of a territory could override the Supreme Court by refusing to pass a slave code, but Lincoln pointed out that if this "lawless" doctrine were accepted then abolitionists by the same logic could refuse to enforce the fugitive slave clause of the Constitution. Lincoln, in other words, showed that Douglas's doctrine of popular sovereignty and Chief Justice Taney's decision that the Constitution endorsed slavery as an inviolable right of property, were logically incompatible with each other. But Lincoln went further, and deeper. Did Douglas deny that black slaves were human beings? Did he maintain that they had no rights at all? Lincoln famously argued that although all men were not created equal in every respect, they were equal in at least one respect: that they were entitled to a share in the fruits of their own labor. Conceding that the African American was "perhaps" not the equal of the white American in some respects, he insisted that in the right to put into his mouth the bread that he had earned with his own hands, he is the equal of every other man.

PROF. BRUCE THOMPSON

RECOMMENDED READING

Destined to become a classic in American history and biography, David Herbert Donald’s Lincoln is a masterly account of how one man’s extraordinary political acumen steered the Union to victory in the Civil War, and of how his soaring rhetoric gave meaning to that agonizing struggle for nationhood and equality. This fully rounded biography of America’s sixteenth President is the product of Donald’s half-century of study of Lincoln and his times. In preparing it, Donald has drawn more extensively than any previous writer on Lincoln’s personal papers and those of his contemporaries, and he has taken full advantage of the voluminous newly discovered records of Lincoln’s legal practice. He presents his findings with the same literary skill and psychological understanding exhibited in his previous biographies, which have received two Pulitzer Prizes. Donald brilliantly traces Lincoln’s rise from humble origins in Kentucky to prominent positions in legal and political circles in Illinois, and then to the pinnacle of the presidency. He shows how, in all these roles, Lincoln repeatedly demonstrated his enormous capacity for growth, which enabled one of the least experienced and most poorly prepared men ever elected to high office to become a giant in the annals of American politics. Much more than a political biography, Donald’s Lincoln reveals the development of the future President’s character and shows how his private life helped to shape his public career.

RECOMMENDED READING

Michael Burlingame,

Abraham Lincoln: A Life,

Johns Hopkins University Press; Abridged edition (October 10, 2023),

ISBN 978-1421445557

(For best deal, OK to purchase used hardcover from Amazon)

3

Week 3: Tuesday, October 22, 2024

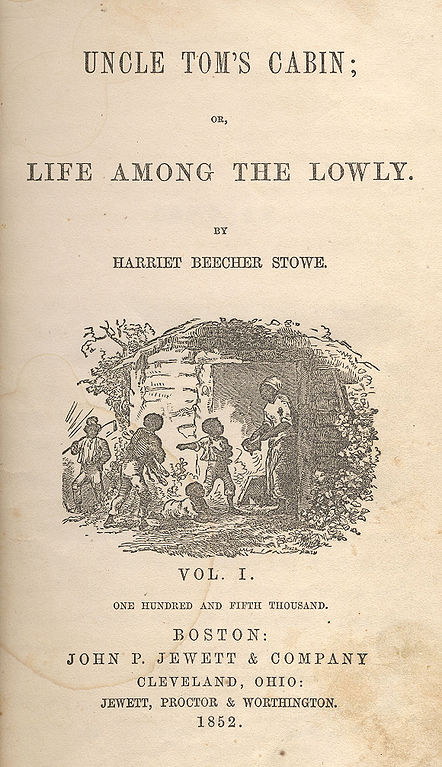

Uncle Tom's Cabin

Week 3

Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U.S., and is said to have "helped lay the groundwork for the American Civil War". Stowe, a Connecticut-born woman of English descent, was part of the religious Beecher family and an active abolitionist. She wrote the sentimental novel to depict the reality of slavery while also asserting that Christian love could overcome slavery. The novel focuses on the character of Uncle Tom, a long-suffering black slave around whom the stories of the other characters revolve. In the United States, Uncle Tom's Cabin was the best-selling novel in the 19th century, except for the Bible. It is credited with helping fuel the abolitionist cause in the 1850s.The influence attributed to the book was so great that a story arose of Abraham Lincoln meeting Stowe at the start of the Civil War and declaring, "So this is the little lady who started this great war."

Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U.S., and is said to have "helped lay the groundwork for the American Civil War". Stowe, a Connecticut-born woman of English descent, was part of the religious Beecher family and an active abolitionist. She wrote the sentimental novel to depict the reality of slavery while also asserting that Christian love could overcome slavery. The novel focuses on the character of Uncle Tom, a long-suffering black slave around whom the stories of the other characters revolve. In the United States, Uncle Tom's Cabin was the best-selling novel in the 19th century, except for the Bible. It is credited with helping fuel the abolitionist cause in the 1850s.The influence attributed to the book was so great that a story arose of Abraham Lincoln meeting Stowe at the start of the Civil War and declaring, "So this is the little lady who started this great war."

4

5

Week 5: Tuesday, November 5, 2024

President Abraham Lincoln

It is hardly a news flash to say that Abraham Lincoln was our greatest President. But what do we mean by "greatness"? It's a term that historians, who spend much of their time debunking reputations, are reluctant to use, because it lacks precision. But let's begin by acknowledging that Lincoln, like Churchill in the following century, (1) changed the course of history by saving a beleaguered democracy; (2) that in the dire circumstances in which he found himself in 1861, only he could have done this (again, like Churchill in 1940); and (3) that his extraordinary character as a leader depended not simply on excellence in one sphere of activity but in multiple roles, including the ability to articulate unforgettably the meaning of the struggle in which he and his people were engaged. Here, too, in his mastery of all the resources of the English language, Churchill resembled him. But there was a difference: Churchill was an aristocrat, born in a palace; Lincoln, as everybody knows, was born in a log cabin and almost entirely self-taught. As Christopher Hitchens remarked in an essay about Lincoln, the other great American presidents—Washington, the Adamses, Jefferson, Madison, the two Roosevelts—were all members of the existing governing class. Lincoln alone came from "the very bone and marrow of the country." Every individual is, of course, unique, and something of a mystery, even to himself. His contemporaries testified to an aura of mystery about Lincoln: "he was the most reticent, secretive man I ever saw—or expect to see" (Judge David Davis). "He never opened his whole soul to any man: he never touched the history or quality of his own nature in the presence of friends" (William Herndon). He left no diary or memoirs, and never sustained an intimate correspondence for very long with one person. "During neither his frequent attacks of melancholy nor his moments of gaiety, when he became a delightful companion, did he expose the secret recesses of his mind." (Don Fehrenbacher). Also remember that it was not only his remarkable character that enabled him to achieve greatness, it was also his intellect. He was almost entirely self-educated, but he must have been one of the most intelligent men ever to occupy the White House. Jefferson may be his only rival in this respect. But Jefferson had the best education the eighteenth century could offer, while Lincoln had barely two years of schooling. Yet Lincoln, as we shall see, read omnivorously, taught himself the principles of rhetoric and argument, became a distinguished lawyer without ever having gone to law school, made an intensive study of Euclidean geometry to develop his powers of logical analysis, meditated deeply on philosophical and theological issues, and, starting from scratch, read his way into the vast literature of military strategy in order to fulfill his responsibilities as Commander in Chief. And as everyone knows, he became the greatest writer among American presidents, surpassing even the author of the Declaration of Independence, the document that was the key to his own political thought.

Bruce Thompson

RECOMMENDED READING

Destined to become a classic in American history and biography, David Herbert Donald’s Lincoln is a masterly account of how one man’s extraordinary political acumen steered the Union to victory in the Civil War, and of how his soaring rhetoric gave meaning to that agonizing struggle for nationhood and equality. This fully rounded biography of America’s sixteenth President is the product of Donald’s half-century of study of Lincoln and his times. In preparing it, Donald has drawn more extensively than any previous writer on Lincoln’s personal papers and those of his contemporaries, and he has taken full advantage of the voluminous newly discovered records of Lincoln’s legal practice. He presents his findings with the same literary skill and psychological understanding exhibited in his previous biographies, which have received two Pulitzer Prizes. Donald brilliantly traces Lincoln’s rise from humble origins in Kentucky to prominent positions in legal and political circles in Illinois, and then to the pinnacle of the presidency. He shows how, in all these roles, Lincoln repeatedly demonstrated his enormous capacity for growth, which enabled one of the least experienced and most poorly prepared men ever elected to high office to become a giant in the annals of American politics. Much more than a political biography, Donald’s Lincoln reveals the development of the future President’s character and shows how his private life helped to shape his public career.

RECOMMENDED READING

"Immediately takes its place as the best one-volume history of the coming of the American Civil War and the war itself. It is a superb narrative history, elegantly written."--Philadelphia Inquirer

"Matchless....The book's political and economic discussions are as engrossing as the descriptions of military campaigns and personalities."--Library Journal

"McPherson cements his reputation as one of the finest Civil War historians....Should become a standard general history of the Civil War period--it's one that will stand up for years to come."--Kirkus Reviews

"The best one-volume treatment of [the Civil War era] I have ever come across. It may actually be the best ever published....I was swept away, feeling as if I had never heard the saga before....Omitting nothing important, whether military, political, or economic, he yet manages to make everything he touches drive the narrative forward. This is historical writing of the highest order."--Hugh Brogan, New York Times Book Review

RECOMMENDED READING

Doris Kearns Goodwin,

Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln,

Simon & Schuster (September 26, 2006),

ISBN 978-0743270755

6

Week 6: Tuesday, November 12, 2024

Jefferson Davis

Week 6

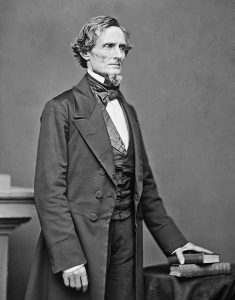

Jefferson F. Davis, 1808 – 1889 was an American politician who served as the first and only president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a member of the Democratic Party before the American Civil War. He was the United States Secretary of War from 1853 to 1857. Davis, the youngest of ten children, was born in Fairview, Kentucky, but spent most of his childhood in Wilkinson County, Mississippi. His eldest brother Joseph Emory Davis secured the younger Davis's appointment to the United States Military Academy. Upon graduating, he served six years as a lieutenant in the United States Army. After leaving the army in 1835, Davis married Sarah Knox Taylor, daughter of general and future President Zachary Taylor. Sarah died from malaria three months after the wedding. Davis became a cotton planter, building Brierfield Plantation in Mississippi on his brother Joseph's land and eventually owning as many as 113 slaves. In 1845, Davis married Varina Howell. During the same year, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives, serving for one year. From 1846 to 1847, he fought in the Mexican–American War as the colonel of a volunteer regiment. He was appointed to the United States Senate in 1847, resigning to unsuccessfully run as governor of Mississippi. In 1853, President Franklin Pierce appointed him Secretary of War. After Pierce's administration ended in 1857, Davis returned to the Senate. He resigned in 1861 when Mississippi seceded from the United States. During the Civil War, Davis guided the Confederacy's policies and served as its commander in chief. (Wikipedia)

Jefferson F. Davis, 1808 – 1889 was an American politician who served as the first and only president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a member of the Democratic Party before the American Civil War. He was the United States Secretary of War from 1853 to 1857. Davis, the youngest of ten children, was born in Fairview, Kentucky, but spent most of his childhood in Wilkinson County, Mississippi. His eldest brother Joseph Emory Davis secured the younger Davis's appointment to the United States Military Academy. Upon graduating, he served six years as a lieutenant in the United States Army. After leaving the army in 1835, Davis married Sarah Knox Taylor, daughter of general and future President Zachary Taylor. Sarah died from malaria three months after the wedding. Davis became a cotton planter, building Brierfield Plantation in Mississippi on his brother Joseph's land and eventually owning as many as 113 slaves. In 1845, Davis married Varina Howell. During the same year, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives, serving for one year. From 1846 to 1847, he fought in the Mexican–American War as the colonel of a volunteer regiment. He was appointed to the United States Senate in 1847, resigning to unsuccessfully run as governor of Mississippi. In 1853, President Franklin Pierce appointed him Secretary of War. After Pierce's administration ended in 1857, Davis returned to the Senate. He resigned in 1861 when Mississippi seceded from the United States. During the Civil War, Davis guided the Confederacy's policies and served as its commander in chief. (Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING

7

Week 7: Tuesday, November 19, 2024

The War Begins

Week 7

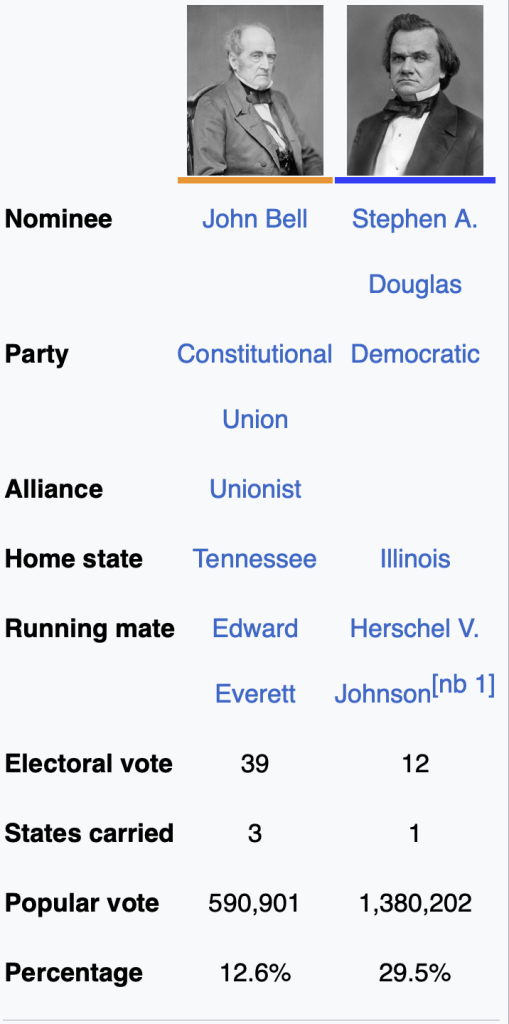

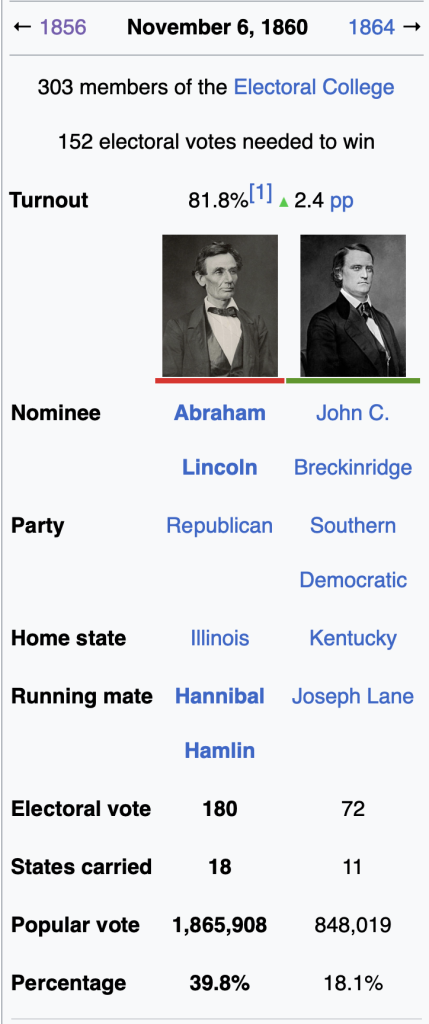

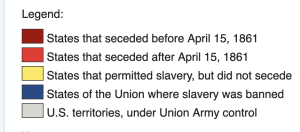

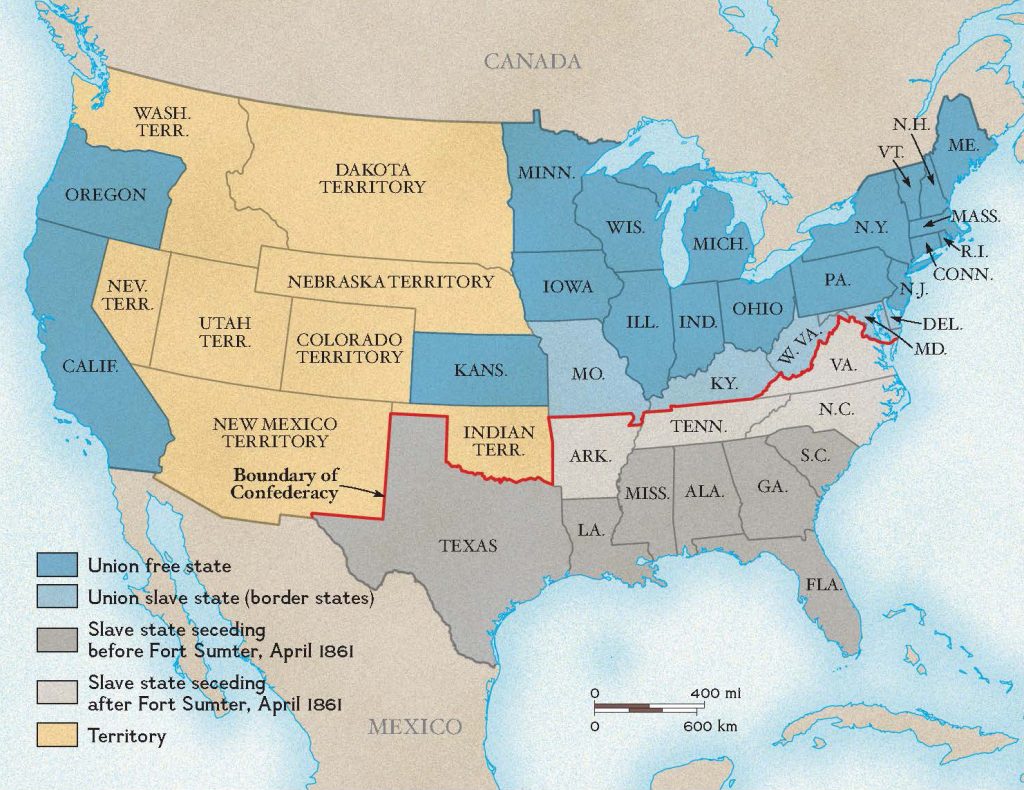

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865) was a civil war in the United States between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), which was formed in 1861 by states that had seceded from the Union. The central conflict leading to the war was a dispute over whether slavery should be permitted to expand into the nation's western territories, leading to more slave states, or be prohibited from doing so, which many believed would place slavery on a course of ultimate extinction. Decades of political controversy over slavery were brought to a head when Abraham Lincoln, who opposed slavery's expansion, won the 1860 U.S. presidential election. Seven southern slave states responded to Lincoln's victory by seceding from the United States and forming the Confederacy. The Confederacy seized U.S. forts and other federal assets within their borders. The war began on April 12, 1861, when the Confederacy bombarded Fort Sumter in South Carolina. A wave of enthusiasm for war swept over both North and South, as military recruitment soared. Four more southern states seceded after the war began and, led by Confederate President Jefferson Davis, the Confederacy asserted control over about a third of the U.S. population in eleven states. Four years of intense combat, mostly in the South, ensued.

RECOMMENDED READING

David Von Drehle,

Rise to Greatness: Abraham Lincoln and America's Most Perilous Year,

Henry Holt and Co.; First Edition (October 30, 2012),

ISBN 978-0805079708

8

Week 8: Tuesday, December 3, 2024

Gettysburg

Week 8

The Battle of Gettysburg was a three-day battle in the American Civil War fought between Union and Confederate forces between July 1 and July 3, 1863, in and around Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle, which was won by the Union, is widely considered the Civil War's turning point, ending the Confederacy's aspirations to establish an independent nation. It was the Civil War's bloodiest battle, claiming over 50,000 combined casualties over three days. In the Battle of Gettysburg, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Potomac defeated attacks by Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, halting Lee's invasion of the north and forcing his retreat.

RECOMMENDED READING

9

Week 9: Tuesday, December 10, 2024

The War Ends

Week 9

"The end of the Confederacy was pitiful. On April 1, 1865, Davis sent his wife Varina away from Richmond, giving her a small Colt and fifty rounds of ammunition. The next day he had to get out of Richmond himself. He went to Danville, to plan guerrilla warfare. By this point General Lee was already in communication with General Grant about a possible armistice, and had indeed privately used the word ‘surrender,’ but he continued to fight fiercely with his army, using it with his customary skills. He dismissed pressure from junior officers to negotiate, and as late as April 8 he took severe disciplinary action against three general officers who, in his opinion, were not fighting in earnest or had deserted their posts. But by the next morning Lee’s army was virtually surrounded. He dressed in his best uniform, wearing, unusually for him, a red silk sash and sword. Having heard the latest news of the position of his troops, and the Union forces, he said: ‘Then there is nothing left me but to go and see General Grant and I would rather die a thousand deaths.’129 The two generals met at Appomattox Court House, Grant dressed in ‘rough garb,’ spattered with mud. Both men were, in fact, carefully dressed for the occasion, as they wished to appear for posterity. The terms were easily agreed, Grant allowing that Southern officers could keep their sidearms and horses. Lee pointed out that, in the South, the enlisted men in the cavalry and artillery also owned their horses. Grant allowed those to be kept too. After Lee’s surrender on April 9, Davis hurried to Greensboro to rendezvous with General Johnston’s army. But in the meantime Johnston had reached an agreement with General Sherman which, in effect, dissolved the Confederacy. Davis gave the terms to his Cabinet, saying he wanted to reject them, but the Cabinet accepted them. Washington, however, did not, and the South had to be content, in the end, with a simple laying down of arms.130 By this time Lincoln was dead. He had summoned Grant to hear his account of the surrender at Appomattox, and he beamed with pleasure when the general told him that the terms had extended not just to the officers but to the men: ‘I told them to go back to their homes and their families and that they would not be molested, if they did nothing more.’ Lincoln expected Sherman to report a similar surrender and he told Grant he expected good news as he had just had one of his dreams which portended such. Grant said he described how ‘he seemed to be in some singular, indescribable vessel and…he was moving with great rapidity to an indefinite shore.’131 Lincoln told his wife (April 14), who said to him, ‘Dear husband, you almost startle me by your great cheerfulness,’ ‘And well may I feel so, Mary. I consider this day, the war has come to a close'."

Johnson, Paul. A History of the American People (pp. 494-495). HarperCollins.

RECOMMENDED READING

10

Week 10: Tuesday, December 17, 2024

March 4, 1865

Week 10

Bruce Thompson on the Second Inaugural:

Lincoln delivered his Second Inaugural Address on Saturday, March 4, 1865, about a month short of Lee's surrender to Grant at Appomattox. Weeks of blustery storms had left Pennsylvania Avenue thick with mud, but the sun appeared just as Lincoln stood up to speak, under the recently completed Capitol dome. This time there were many hundreds of free black people, including the great abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass, as well as black soldiers in uniform, in the audience. The address, at four paragraphs, 26 sentences, 703 words, is longer than the Gettysburg Address, but shorter than any other inaugural address, except for the first one, by George Washington.

Lincoln:

"Fellow-Countrymen:

At this second appearing to take the oath of the Presidential office there is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first. Then a statement somewhat in detail of a course to be pursued seemed fitting and proper. Now, at the expiration of four years, during which public declarations have been constantly called forth on every point and phase of the great contest which still absorbs the attention and engrosses the energies of the nation, little that is new could be presented. The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well known to the public as to myself, and it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory and encouraging to all. With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured."

Surely this is a modest opening: no biblical "four score and seven years ago," but rather "this second appearing." Not "my second appearing," for Lincoln once again has chosen to suppress the first person singular pronoun: there is one use of "myself" and one of "I" in this paragraph ("I trust"), but everywhere else in the speech he uses the inclusive plural. He begins, modestly, by telling us what he will not do in the speech: he will not render an account of the North's great victories on the battlefields ("little that is new could be presented"). Nor will he celebrate his own achievements, or even predict the final outcome of the war ("no prediction in regard to it is ventured"). Notice how he shifts to the passive voice to avoid the first person singular pronoun.

RECOMMENDED READING

All

Week 1: Wed., Oct. 9, 2024

Our First Revolution

WEEK 1

We begin our study of the American Revolution with a look back into English history. The roots of the American Revolution are to be found in the great revolutionary upheaval of 1688 in England. In that year the English people rose up again against the king (James II) who was trying to impose upon them his own personal Roman Catholic religion. The English people had made it clear in their parliament again and again that they were an Anglican nation with the religion that was their own version of Protestantism, created during the reign of Henry VIII, and did not want to join the international Roman Catholic Church. King James II tried and tried and tried to drag the nation into his own Roman Catholic beliefs. This failed in 1688, when he was pushed out of office and sent into permanent exile in France. In the years immediately succeeding this event, the English people wrote a "Bill of Rights" which was imposed upon the new Protestant monarchs William and Mary. This event and the literature that accompanied the event (John Locke) provided the intellectual and legal basis for the American Revolution a century later. The title of our lecture is taken from a wonderful book by the American political scientist Michael Barone.(Our First Revolution)

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

From the Publisher:

"For too long we’ve lacked a compact, inexpensive, authoritative, and compulsively readable book that offers American readers a clear, informative, and inspiring narrative account of their country. Such a fresh retelling of the American story is especially needed today, to shape and deepen young Americans’ sense of the land they inhabit, help them to understand its roots and share in its memories, all the while equipping them for the privileges and responsibilities of citizenship in American society. The existing texts simply fail to tell that story with energy and conviction. Too often they reflect a fragmented outlook that fails to convey to American readers the grand trajectory of their own history. A great nation needs and deserves a great and coherent narrative, as an expression of its own self-understanding and its aspirations; and it needs to be able to convey that narrative effectively. Of course, it goes without saying that such a narrative cannot be a fairy tale of the past. It will not be convincing if it is not truthful. But as Land of Hope brilliantly shows, there is no contradiction between a truthful account of the American past and an inspiring one. Readers of Land of Hope will find both in its pages."

REVIEWS

“At a time of severe partisanship that has infected many accounts of our nation’s past, this brilliant new history, Land of Hope, written in lucid and often lyrical prose, is much needed. It is accurate, honest, and free of the unhistorical condescension so often paid to the people of America’s past. This generous but not uncritical story of our nation’s history ought to be read by every American. It explains and justifies the right kind of patriotism.”― Gordon S. Wood, author of Friends Divided: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson

“We’ve long needed a readable text that truly tells the American story, neither hiding the serious injustices in our history nor soft-pedaling our nation’s extraordinary achievements. Such a text cannot be a mere compilation of facts, and it certainly could not be written by someone lacking a deep understanding and appreciation of America’s constitutional ideals and institutions. Bringing his impressive skills as a political theorist, historian, and writer to bear, Wilfred McClay has supplied the need.”― Robert P. George, McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence, Princeton University

“No one has told the story of America with greater balance or better prose than Wilfred McClay. Land of Hope is a history book that you will not be able to put down. From the moment that ‘natives’ first crossed here over the Bering Strait, to the founding of America’s great experiment in republican government, to the horror and triumph of the Civil War...McClay’s account will capture your attention while offering an unforgettable education.”― James W. Ceaser, Professor of Politics, University of Virginia

Week 2: Wed., Oct. 16, 2024

18th Century Britain

WEEK 2

The revolutionary activities that unfolded in the colonies of North America during the 1760s and 1770s were all actions taken by Englishmen. The ideas, the books, the legal arguments, of all the major revolutionaries, Samuel Adams, John Adams, John Dickinson, Ben Franklin, all of these ideas were rooted in the events in England during the 1700s. The revolutionaries in Boston had no desire to break away from their English homeland. They thought like Englishman. They wrote books rooted in English legal traditions. They responded to the latest publications in London. And they were supported in England by voices in the English parliament. Therefore, as the revolutionary movement developed in Boston, Philadelphia and Virginia, the whole movement was filled with English ideas, books, and language. In our second week we will talk about this 18th century England with its Hanoverian kings and it's brilliant legal scholars.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

RECOMMENDED BOOK

Week 3: Wed., Oct. 23, 2024

18th Century France

WEEK 3

The revolutionaries in Boston in the 1760s and 1770s were first of all Englishmen. But they read French books. They knew the literature of the French Enlightenment well, Voltaire, Montesquieu, Rousseau, and others as well as the literature coming out of England. And as the crisis evolved, everyone in Boston and Philadelphia began to realize that if there was a break with England, the one most important nation that might help the colonies was the nation of France. The French Connection was complicated by the fact that France also was going through a pre-revolutionary phase. By the 1770s, Paris was on fire with revolutionary ideas and books that were widely read. But the overriding issue for the French government was any alliance that would help them fight their traditional enemies on the British island. Therefore, some alliance between the American colonies and the French nation was obvious to all. King Louis XVI was very much in favor of French help for the American colonies. If you would like to know something about the French Revolution here is a very useful short introduction.

RECOMMENDED READING

William Doyle,

The French Revolution: A Very Short Introduction,

Oxford University Press; 1 edition (December 6, 2001),

ISBN 0192853961

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

Week 4: Wed., Oct. 30, 2024

Empire

WEEK 4

"The Seven Years’ War was particularly important to the future of America, where it came to be referred to as the French and Indian War, and would last from 1754 to 1763. The French and Indian War was enormously consequential. It would dramatically change the map of North America. It would also force a rethinking of the entire relationship between England and her colonies and bring to an end any remaining semblance of the “salutary neglect” policy. And that change, in turn, would help pave the way to the American Revolution."

McClay, Wilfred M.. Land of Hope (p. 35). Encounter Books.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

Week 5: Wed., Nov. 6, 2024

The Boston Massacre

WEEK 5

The Boston Massacre was a confrontation in Boston on March 5, 1770, in which nine British soldiers shot several of a crowd of three or four hundred who were harassing them verbally and throwing various projectiles. The event was heavily publicized as "a massacre" by leading Patriots such as Paul Revere and Samuel Adams. British troops had been stationed in the Province of Massachusetts Bay since 1768 in order to support crown-appointed officials and to enforce unpopular Parliamentary legislation. Amid tense relations between the civilians and the soldiers, a mob formed around a British sentry and verbally abused him. He was eventually supported by seven additional soldiers, led by Captain Thomas Preston, who were hit by clubs, stones, and snowballs. Eventually, one soldier fired, prompting the others to fire without an order by Preston. The gunfire instantly killed three people and wounded eight others, two of whom later died of their wounds. Depictions, reports, and propaganda about the event heightened tensions throughout the Thirteen Colonies, notably the colored engraving produced by Paul Revere which you can see below.

David McCullough on John Adams and the British soldiers arrested and accused of murder:

"Samuel Adams was quick to call the killings a 'bloody butchery' and to distribute a print published by Paul Revere vividly portraying the scene as a slaughter of the innocent, an image of British tyranny, the Boston Massacre, that would become fixed in the public mind. The following day thirty-four-year-old John Adams was asked to defend the soldiers and their captain, when they came to trial. No one else would take the case, he was informed. . . .Adams accepted, firm in the belief, as he said, that no man in a free country should be denied the right to counsel and a fair trial, and convinced, on principle, that the case was of utmost importance. As a lawyer, his duty was clear. That he would be hazarding his hard-earned reputation and, in his words, 'incurring a clamor and popular suspicions and prejudices' against him, was obvious, and if some of what he later said on the subject would sound a little self-righteous, he was also being entirely honest. Only the year before, in 1769, Adams had defended four American sailors charged with killing a British naval officer who had boarded their ship with a press gang to grab them for the British navy. The sailors were acquitted on grounds of acting in self-defense, but public opinion had been vehement against the heinous practice of impressment. Adams had been in step with the popular outrage, exactly as he was out of step now. He worried for Abigail, who was pregnant again, and feared he was risking his family’s safety as well as his own, such was the state of emotions in Boston."

McCullough, David. John Adams . Simon & Schuster.

John Adams willingness to defend these British soldiers was one of the most courageous acts of his lifetime, and although at the time of the trial Bostonians ranted and raged against him, later when the trial was over and temperatures cooled down, it became clear to the larger public that Adams was an extraordinarily brave and wise man. The trial and the acquittal set Adams apart from other Bostonian leaders.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

Week 6: Wed., Nov. 13, 2024

Lexington and Concord

WEEK 6

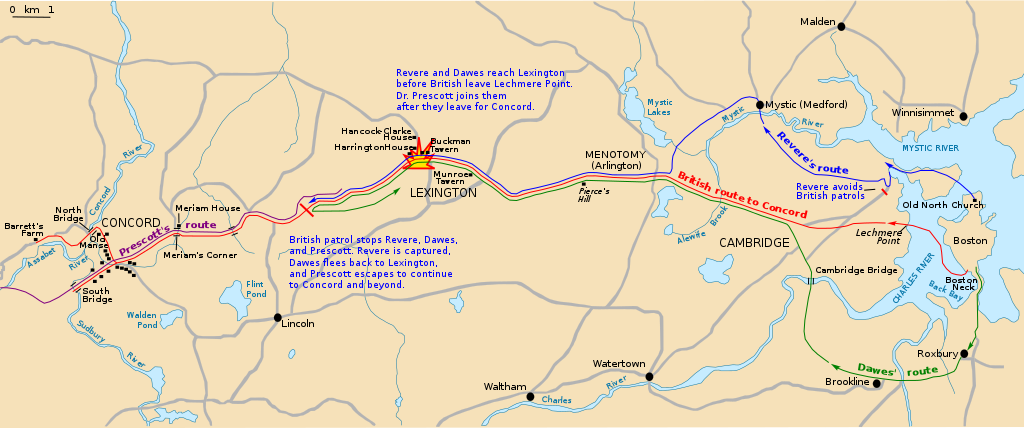

The Battles of Lexington and Concord, were the leading military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, Lincoln, Menotomy (present-day Arlington), and Cambridge. They marked the outbreak of armed conflict between the Kingdom of Great Britain and Patriot militias from America's thirteen colonies. In late 1774, Colonial leaders adopted the Suffolk Resolves in resistance to the alterations made to the Massachusetts colonial government by the British parliament following the Boston Tea Party. The colonial assembly responded by forming a Patriot provisional government known as the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and calling for local militias to train for possible hostilities. The Colonial government effectively controlled the colony outside of British-controlled Boston. In response, the British government in February 1775 declared Massachusetts to be in a state of rebellion. About 700 British Army regulars in Boston, under Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith, were given secret orders to capture and destroy Colonial military supplies reportedly stored by the Massachusetts militia at Concord. Through effective intelligence gathering, Patriot leaders had received word weeks before the expedition that their supplies might be at risk and had moved most of them to other locations. On the night before the battle, warning of the British expedition had been rapidly sent from Boston to militias in the area by several riders, including Paul Revere and Samuel Prescott, with information about British plans. The initial mode of the Army's arrival by water was signaled from the Old North Church in Boston to Charlestown using lanterns to communicate "one if by land, two if by sea". The first shots were fired just as the sun was rising at Lexington. Eight militiamen were killed, including Ensign Robert Munroe, their third in command. The British suffered only one casualty. The militia was outnumbered and fell back, and the regulars proceeded on to Concord, where they broke apart into companies to search for the supplies. At the North Bridge in Concord, approximately 400 militiamen engaged 100 regulars from three companies of the King's troops at about 11:00 am, resulting in casualties on both sides. The outnumbered regulars fell back from the bridge and rejoined the main body of British forces in Concord. The British forces began their return march to Boston after completing their search for military supplies, and more militiamen continued to arrive from the neighboring towns. Gunfire erupted again between the two sides and continued throughout the day as the regulars marched back towards Boston. Upon returning to Lexington, Lt. Col. Smith's expedition was rescued by reinforcements under Brigadier General Hugh Percy, a future Duke of Northumberland styled at this time by the courtesy title Earl Percy. The combined force of about 1,700 men marched back to Boston under heavy fire in a tactical withdrawal and eventually reached the safety of Charlestown. The accumulated militias then blockaded the narrow land accesses to Charlestown and Boston, starting the siege of Boston. Ralph Waldo Emerson describes the first shot fired by the Patriots at the North Bridge in his "Concord Hymn" as the "shot heard round the world". (Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

RECOMMENDED READING

From the Publisher:America’s beloved and distinguished historian presents, in a book of breathtaking excitement, drama, and narrative force, the stirring story of the year of our nation’s birth, 1776, interweaving, on both sides of the Atlantic, the actions and decisions that led Great Britain to undertake a war against her rebellious colonial subjects and that placed America’s survival in the hands of George Washington. In this masterful book, David McCullough tells the intensely human story of those who marched with General George Washington in the year of the Declaration of Independence—when the whole American cause was riding on their success, without which all hope for independence would have been dashed and the noble ideals of the Declaration would have amounted to little more than words on paper. Based on extensive research in both American and British archives, 1776 is a powerful drama written with extraordinary narrative vitality. It is the story of Americans in the ranks, men of every shape, size, and color, farmers, schoolteachers, shoemakers, no-accounts, and mere boys turned soldiers. And it is the story of the King’s men, the British commander, William Howe, and his highly disciplined redcoats who looked on their rebel foes with contempt and fought with a valor too little known.

Week 7: Wed., Nov. 20, 2024

Philadelphia 1775-1776

WEEK 7

The Second Continental Congress was the 1775-76 meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolution and its associated Revolutionary War that established American independence from the British Empire. The Congress created a new country that it first named the United Colonies, and in 1776, renamed the United States of America. The Congress began convening in Philadelphia, on May 10, 1775, with representatives from 12 of the 13 colonies, after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. The Second Continental Congress succeeded the First Continental Congress, which also met in Philadelphia from September 5 to October 26, 1774. The Second Congress functioned as the de facto national government at the outset of the Revolutionary War by raising militias, directing strategy, appointing diplomats, and writing petitions such as the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms and the Olive Branch Petition. All 13 colonies were represented by the time the Congress adopted the Lee Resolution, which declared independence from Britain on July 2, 1776, and the Congress unanimously agreed to the Declaration of Independence two days later. Congress functioned as the provisional government of the United States of America through March 1, 1781. During this period, it successfully managed the war effort, drafted the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, adopted the first U.S. constitution, secured diplomatic recognition and support from foreign nations, and resolved state land claims west of the Appalachian Mountains. Many of the delegates who attended the Second Congress had also attended the First. They again elected Peyton Randolph as president of the Congress and Charles Thomson as secretary. Notable new arrivals included Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania and John Hancock of Massachusetts. Within two weeks, Randolph was summoned back to Virginia to preside over the House of Burgesses; Hancock succeeded him as president, and Thomas Jefferson replaced him in the Virginia delegation. The number of participating colonies also grew, as Georgia endorsed the Congress in July 1775 and adopted the continental ban on trade with Britain. (Wikipedia)(/p>

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

RECOMMENDED READING

From the Publisher:America’s beloved and distinguished historian presents, in a book of breathtaking excitement, drama, and narrative force, the stirring story of the year of our nation’s birth, 1776, interweaving, on both sides of the Atlantic, the actions and decisions that led Great Britain to undertake a war against her rebellious colonial subjects and that placed America’s survival in the hands of George Washington. In this masterful book, David McCullough tells the intensely human story of those who marched with General George Washington in the year of the Declaration of Independence—when the whole American cause was riding on their success, without which all hope for independence would have been dashed and the noble ideals of the Declaration would have amounted to little more than words on paper. Based on extensive research in both American and British archives, 1776 is a powerful drama written with extraordinary narrative vitality. It is the story of Americans in the ranks, men of every shape, size, and color, farmers, schoolteachers, shoemakers, no-accounts, and mere boys turned soldiers. And it is the story of the King’s men, the British commander, William Howe, and his highly disciplined redcoats who looked on their rebel foes with contempt and fought with a valor too little known.

RECOMMENDED READING

Pauline Maier,

American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence,

Vintage,

ISBN 978-0679779087

NEXT WEEK IS THANKSGIVING WEEK

NO CLASSES ALL WEEK OF NOV 25-29 2024

Week 8: Wed., Dec. 4, 2024

Ben Franklin in Paris

WEEK 8

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

RECOMMENDED READING

Walter Isaacson,

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life,

Simon & Schuster (June 1, 2004),

ISBN 978-0743258074

Week 9: Wed., Dec. 11, 2024

Washington at War

WEEK 9

George Washington: ""I have often thought how much happier I should have been if, instead of accepting a command under such circumstances, I should have taken my musket upon my Shoulder & entered the Ranks or … had retir'd to the back country & lived in a Wig-wam."

—George Washington to Joseph Reed, 14 January 1776

WASHINGTON'S WAR BEGINS IN BOSTON SUMMER 1775

The siege of Boston (April 19, 1775 – March 17, 1776) was the opening phase of the American Revolutionary War. New England militiamen prevented the British Army from moving by land, and it was garrisoned in Boston, Massachusetts Bay. Both sides had to deal with resource, supply, and personnel issues over the course of the siege. British resupply and reinforcement was limited to sea access, which was impeded by American vessels. The British abandoned Boston after 11 months and transferred their troops and equipment to Nova Scotia. The siege began on April 19 after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, when Massachusetts militias blocked land access to Boston. The Continental Congress formed the Continental Army from the militias involved in the fighting and appointed George Washington as Commander in Chief. In June 1775, the British seized Bunker Hill, from which the Continentals were preparing to bombard the city, but their casualties were heavy and their gains insufficient to break the Continental Army's control over land access to Boston. After this, the Americans laid siege to the city; no major battles were fought during this time, and the conflict was limited to occasional raids, minor skirmishes, and sniper fire. British efforts to supply their troops were significantly impeded by the smaller but more agile American forces operating on land and sea, and the British consequently suffered from a continual lack of food, fuel, and supplies. In November 1775, George Washington sent Henry Knox on a mission to bring the heavy artillery that had recently been captured at Fort Ticonderoga. In a technically complex and demanding operation, Knox brought the cannons to Boston in January 1776, and this artillery fortified Dorchester Heights which overlooked Boston harbor. This development threatened to cut off the British supply lifeline from the sea. British commander William Howe saw his position as indefensible, and he withdrew his forces from Boston to Halifax, Nova Scotia on March 17.

WASHINGTON IN NEW YORK

David McCullough, 1776: "At Boston, Washington had known exactly where the enemy was, and who they were, and what was needed to contain them. At Boston the British had been largely at his mercy, and especially once winter set it. Here, with their overwhelming naval might and absolute control of the waters, they could strike at will and from almost any direction. The time and place of the battle would be entirely their choice, and this was the worry overriding all others….At Boston, Washington had benefited from a steady supply of valuable intelligence coming out of the besieged town, while Howe had known little or nothing of Washington's strengths or intentions. Here, with so much of the population still loyal to the king, the situation was the reverse." Washington: "The designs of the Enemy are too much behind the Curtain for me to form any accurate opinion of their Plan of operations… we are left to wander in the field of conjecture."

The British at New York: Joseph Ellis: "In a nearly miraculous burst of logistical energy, Great Britain assembled a fleet of 427 ships equipped with 1,200 cannons to transport 32,000 soldiers and 10,000 sailors across the Atlantic. It was the largest amphibious operation ever attempted by any European power, with an attack force larger than the population of Philadelphia, the biggest city in America" Last to arrive at New York, "was Admiral Richard Howe with by far the largest fleet, more than 150 ships with 20,000 troops and a six-month supply of food and munitions, by itself the largest armada to cross the Atlantic before the American Expeditionary Force in WWI."

This sketch by a British officer on Staten Island shows part of the king’s fleet anchored in the Narrows, across from Long Island on July 12, 1776. Admiral Howe’s flagship, Eagle, can be seen in the middle distance, approaching from the open sea.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

RECOMMENDED READING

From the Publisher:In Washington: A Life celebrated biographer Ron Chernow provides a richly nuanced portrait of the father of our nation. With a breadth and depth matched by no other one-volume life of Washington, this crisply paced narrative carries the reader through his troubled boyhood, his precocious feats in the French and Indian War, his creation of Mount Vernon, his heroic exploits with the Continental Army, his presiding over the Constitutional Convention, and his magnificent performance as America's first president. Despite the reverence his name inspires, Washington remains a lifeless waxwork for many Americans, worthy but dull. A laconic man of granite self-control, he often arouses more respect than affection. In this groundbreaking work, based on massive research, Chernow dashes forever the stereotype of a stolid, unemotional man. A strapping six feet, Washington was a celebrated horseman, elegant dancer, and tireless hunter, with a fiercely guarded emotional life. Chernow brings to vivid life a dashing, passionate man of fiery opinions and many moods. Probing his private life, he explores his fraught relationship with his crusty mother, his youthful infatuation with the married Sally Fairfax, and his often conflicted feelings toward his adopted children and grandchildren. He also provides a lavishly detailed portrait of his marriage to Martha and his complex behavior as a slave master. At the same time, Washington is an astute and surprising portrait of a canny political genius who knew how to inspire people. Not only did Washington gather around himself the foremost figures of the age, including James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson, but he also brilliantly orchestrated their actions to shape the new federal government, define the separation of powers, and establish the office of the presidency. In this unique biography, Ron Chernow takes us on a page-turning journey through all the formative events of America's founding. With a dramatic sweep worthy of its giant subject, Washington is a magisterial work from one of our most elegant storytellers.

RECOMMENDED READING

David Hackett Fischer,

Washington's Crossing (Pivotal Moments in American History),

Oxford University Press; Reprint edition (February 1, 2006),

ISBN 978-0195181593

Week 10: Wed., Dec. 18, 2024

Peace of Paris 1783

WEEK 10

1773 Dec. 16, Boston Tea Party

1774 Jan, Boston under British lockdown

1775 April 19, Battle of Lexington & Concord

1775 June 17 Battle of Bunker Hill

1775 July George Washington takes command in Boston

1775 Nov. Henry Knox goes to Ticonderoga for guns

1776 Jan. Knox and guns arrive at Boston

1776 Jan. Thomas Paine publishes "Common Sense"

1776 Mar. Washington puts guns on Dorchester Heights

1776 March 17 British evacuate Boston

1776 July British arrive in New York

1776 July 4, Declaration of Independence

1776 Aug. 27 Battle of Brooklyn Washington defeated

1776 Nov. 16 Washington loses New York

1776 Dec. 25/26 Washington wins Battle of Trenton

1777 Jan. 3, Washington wins Battle of Princeton

1777 Sept 19-Oct 7, Americans win Battle of Saratoga; brings in French aid

1778 Feb. 6, French-American alliance announced

1778 June 28, Battle of Monmouth, Geo Washington saves the day

1779 Feb. 3, Battle of Port Royal Island SC

1779 Nov Washington’s Main Army begins camping at Morristown, NJ

1780 Oct 7, Americans win Battle of Kings Mountain;

Thomas Jefferson called the battle "The turn of the tide of success."

1781 Mar 2, Articles of Confederation adopted

1781 Sep 28-Oct 19 - Siege of Yorktown, VA

1781 Oct 19, General Cornwallis officially surrenders at Yorktown, VA

1783 Sept 3, US and British sign Treaty of Paris

RECOMMENDED READING

The Chernow biography is the best source for the later war and its conclusion.