Week 11

Week 11: Monday, January 8, 2024

Spain and Islam

WEEK 11

In 711, the armies of Islam crossed the Straits of Gibraltar and conquered almost all of Spain. This week we will discuss the impact Islam had on Spain and then all of Europe.

Islam is the monotheistic religion articulated by the Qur’an, a text considered by its adherents to be the verbatim word of God and by the teachings and normative example (called the Sunnah and composed of Hadith) of Muhammad, considered by them to be the last prophet of God. An adherent of Islam is called a Muslim. Muslims believe that God is one and incomparable and the purpose of existence is to worship God. Muslims also believe that Islam is the complete and universal version of a faith that was revealed at many times and places before, including through Abraham, Moses and Jesus, whom they consider prophets. They maintain that previous messages and revelations have been partially changed or corrupted over time, but consider the Qur'an to be both the unaltered and the final revelation of God. Religious concepts and practices include the five pillars of Islam, which are basic concepts and obligatory acts of worship, and following Islamic law, which touches on virtually every aspect of life and society, providing guidance on multifarious topics from banking and welfare, to warfare and the environment. The majority of Muslims are Sunni, being over 75-90% of all Muslims. The second largest sect, Shia, makes up 10-20%. About 13% of Muslims live in Indonesia, the largest Muslim country, 25% in South Asia, 20% in the Middle East, 2% in Central Asia, 4% in the remaining South East Asian countries, and 15% in Sub-saharan Africa. Sizable communities are also found in China and Russia, and parts of Europe. With over 1.5 billion followers or over 22% of earth's population as of 2009, Islam is the second-largest religion in the world.(Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING

Bernard Ellis Lewis,

Islam: The Religion and the People,

Pearson Prentice Hall; 1 edition (August 29, 2008),

ISBN 0132230852

Praise for Bernard Lewis:

"For newcomers to the subject, Bernard Lewis is the man." TIME Magazine

“The doyen of Middle Eastern studies." The New York Times

“No one writes about Muslim history with greater authority, or intelligence, or literary charm.” British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper.

If you would like to read one book for a general introduction to Islam written by a major European scholar then this book by Bernard Lewis is the best.

The book is in our Institute library.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE ACADEMIC YEAR

This new history of the Middles Ages has just appeared from the best-selling author Dan Jones. It is perfect for us. The organization and the coverage is excellent. It reads well and is a pleasure. The cost of it is about 20$ from Amazon, either hardcover or paperback. If you prefer the lighter paperback then choose it, but the hardcore will endure better. Please use our link on this page to buy from Amazon because we get credit($) for each purchase.

Here are just a few of the reviews.

"Not only an engrossing read about the distant past, both informative and entertaining, but also a profoundly thought-provoking view of our not-really-so-‘new’ present . . . All medieval history is here, beautifully narrated . . . The vision takes in whole imperial landscapes but also makes room for intimate portraits of key individuals, and even some poems."—Wall Street Journal

"A lively history . . . [Jones] has managed to touch every major topic. As each piece of the puzzle is placed into position, the modern world gradually comes into view . . . Powers and Thrones provides the reader with a framework for understanding a complicated subject, and it tells the story of an essential era of world history with skill and style."—The New York Times

The New York Times bestselling author returns with an epic history of the medieval world—a rich and complicated reappraisal of an era whose legacy and lessons we are still living with today.

12

Week 12: Monday, January 15, 2024

Aquitaine

WEEK 12

Aquitaine is an historical region of southwestern France. It is situated in the southwest corner of France, along the Atlantic Ocean and the Pyrenees mountain range on the border with Spain, and for most of its written history Bordeaux has been a vital port and administrative center. There are traces of human settlement by prehistoric peoples, especially in the Périgord, but the earliest attested inhabitants in the south-west were the Aquitani, who were not considered Celtic people, but more akin to the Iberians (see Gallia Aquitania). The original Aquitania (named after the inhabitants) at the time of Caesar's conquest of Gaul included the area bounded by the river Garonne, the Pyrenees and the Atlantic Ocean. The name may stem from Latin 'aqua', maybe derived from a general geographical feature. In 392, the Roman imperial provinces were restructured as Aquitania Prima (north-east), Aquitania Secunda (centre) and Aquitania Tertia, better known as Novempopulania in the south-west. Accounts of Aquitania during the Early Middle Ages are imprecise, but there was much unrest. The Visigoths were called into Gaul as foederati, legalizing their status within the Empire. Eventually they established themselves as the de facto rulers in south-west Gaul as central Roman rule collapsed. Visigoths established their capital in Toulouse, but their tenure on Aquitaine was feeble. In 507, they were expelled south to Hispania after their defeat in the Battle of Vouillé by the Franks, who became the new rulers in the area to the south of the Loire. The Roman Aquitania Tertia remained in place, where a duke was appointed to hold a grip over the Basques (Vascones/Wascones, rendered Gascons in English). These dukes were quite detached from central Frankish overlordship, sometimes governing as independent rulers with strong ties to their kinsmen south of the Pyrenees. As of 660, the foundations for an independent Aquitaine/Vasconia polity were established by the duke Felix of Aquitaine, a magnate (potente(m)) from Toulouse, probably of Gallo-Roman stock. Despite its nominal submission to the Frankish Merovingians, the ethnic make-up of the new Aquitanian realm was not Frankish, but Gallo-Roman north of the Garonne and in main towns and Basque, especially south of the Garonne. In 721, the Aquitanian duke fended Umayyad troops (Sarracens) off at Toulouse, but in 732 the King of the Franks, Charles Martel led the effort to defeat the Islamic invaders at the Battle of Poitiers. In 781, Charlemagne decided to proclaim his son Louis King of Aquitaine within the Carolingian Empire, ruling over a realm comprising the Duchy of Aquitaine and the Duchy of Vasconia. He suppressed various Basque (Gascon) uprisings, even venturing into the lands of Pamplona past the Pyrenees after ravaging Gascony, with a view to imposing his authority also in the Vasconia to south of Pyrenees. According to his biography, he achieved everything he wanted and after staying overnight in Pamplona, on his way back his army was attacked in Roncevaux in 812, but narrowly escaped an engagement at the Pyrenean passes. Seguin (Sihiminus), count of Bordeaux and Duke of Vasconia, seemed to have attempted a detachment from the Frankish central authority on Charlemagne's death. The new emperor Louis the Pious reacted by removing him from his capacity, which stirred the Basques into rebellion. The king in turn sent his troops to the territory, obtaining their submission in two campaigns and killing the duke, while his family crossed the Pyrenees and continued to foment risings against Frankish power. In 824, the 2nd Battle of Roncevaux took place, in which counts Aeblus and Aznar, Frankish vassals from the Duchy of Vasconia sent by the new King of Aquitaine, Pepin, King of the Franks, were captured by the joint forces of Iñigo Arista and the Banu Qasi. Before Pepin's death, emperor Louis had appointed a new king in 832, his son Charles the Bald, while the Aquitanian lords elected Pepin II as king. This struggle for control of the kingdom led to a constant period of war between Charles, loyal to his father and the Carolingian power, and Pepin II, who relied more on the support of Basque and Aquitanian lords. Aquitaine after the Treaty of Verdun: After the 843 Treaty of Verdun, the defeat of Pepin II and the death of Charles the Bald, the Kingdom of Aquitaine (subsumed in West Francia) ceased to have any relevance and the title of King of Aquitaine took on a nominal value. In 1058, the Duchy of Vasconia (Gascony) and Aquitaine merged under the rule of William VIII, Duke of Aquitaine. Aquitaine passed to France in 1137 when the duchess Eleanor of Aquitaine married Louis VII of France, but their marriage was annulled in 1152. When Eleanor's new husband became King Henry II of England in 1154, the area became an English possession, and a cornerstone of the Angevin Empire. Aquitaine remained English until the end of the Hundred Years' War in 1453, when it was annexed by France. (Wikipedia)

13

Week 13: Monday, January 22, 2024

Kings and Queens of Europe

WEEK 13

The Medieval monarch established order and unit within the chaos of the post-Roman Europe. The best example of how this worked was in England. England was a small kingdom, not much larger than some of the great duchies of France or Germany. An active king could visit most parts of his realm with some regularity. Moreover, a long series of conquests (especially 1066) had prevented the rise of strong provincial rulers or the development of deeply entrenched provincial institutions. Because no areas had been monopolized by provincial dynasties the king still had lands and rights of justice in all parts of his realm. Because his lands and rights were so widely dispersed he had to have agents everywhere —sheriffs and bailiffs, keepers of castles and forests. Keeping track of the income produced by hundreds of different sources made plain the need for a central financial office: the English Exchequer of the early 12th century. The Exchequer kept meticulously detailed records; it had a highly professional staff; it became so solidly established that it could function even in periods of civil war. Moreover, if all titles were based on grants or confirmation by the king, then it was natural that the king and his court would be asked to settle disputes over possession of land and the rights which went with land. "Court" is of course an ambiguous word; at first it meant no more than the great men—bishops, barons, and household officials—who were with the king. But even in the 11th century some of these men were more apt to be called on to deal with legal problems than others, and during the 12th century a group of royal justices appeared. Soon there were circuit judges, juries, writs. The new procedure of the royal courts was designed to cut down delay, to get quick, easily enforceable decisions in cases where decisions had been hard to reach. There was a deliberate attempt to reduce complicated problems to simple questions that could be answered by men with little knowledge of law or of remote events. Thus in cases involving land tenure the most common question was: "Who was last in peaceful possession?" not "Who has best title?" The question was answered by a group of neighbors, drawn from the law-abiding men of the district in which the property lay. They gave a collective response, based on their own knowledge and observations; there was no need for testimony and little opportunity for legal arguments. This procedure rapidly developed into trial by jury… an improvement on earlier, irrational procedures such as trial by combat or ordeals. In any case, knights, lesser landholders, and ordinary freemen in England found that the jury gave them some protection against the rich and the powerful. They flocked to the king's courts; by the 13th century all cases of any importance and significance whatever were heard by the king's judges. The royal government had succeeded in involving almost the entire free population of the country in the work of the law courts, either as litigants or as jurors. Local privileges and customs did not have time to harden into divisive institutions. The judicial and financial systems created in the 11th and 12th centuries could operate uniformly throughout the country. The king's justices, or even the king himself could give final judgments at once and anywhere. There was no need for elaborate individual negotiations with hundreds of lords and local communities when a tax was to be raised; the Council, and later the Parliament, could speak for the whole realm. Conversely, the English government could rely on unpaid local notables to do a great deal of the work of local administration. Energies which elsewhere were wasted in the defense of local privileges could be used in England to help the central government carry out its policies. If the English bureaucracy was inefficient, it was so at less cost than in other nascent states. Medieval states were law-states. They had acquired their power largely by developing their judicial institutions and by protecting the property rights of the possessing classes. A corollary of this emphasis on law was an emphasis on the right of consent. Existing usages, guaranteed by law, were a form of property and could not be changed without due process. Here is the background to the invention of Parliament: the principles that important decisions should be made publicly, that customs should not be changed without general agreement, that consent was necessary when the superior needed extraordinary additions to his income formed part of the general climate of opinion. These meetings, where important men of all classes came together, were convenient occasions for voicing grievances, for demanding investigations and reforms. All of this work of unifying the nation around functioning law courts was the conscious policy of King Henry II. He knew exactly what he was doing. His courts, often with his personal presence presiding, rendered fair justice. And the results of this justice was a united nation. It was exactly this unified nation that forced King John to sit down at the table and sign the most important Medieval document of them all: the Magna Carta. (some of the above text is taken from a very famous book by the historian Joseph Strayer, On the Medieval Origins of the Modern State (Princeton Classics, 21) Paperback.)

RECOMMENDED READING

Joseph Strayer,

On the Medieval Origins of the Modern State (Princeton Classics, 21),

Princeton University Press; Revised edition (March 29, 2016),

ISBN 978-0691169330

14

Week 14: Monday, January 29, 2024

The Crusades

WEEK 14

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Christian Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these military expeditions are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were intended to reconquer Jerusalem and its surrounding area from Muslim rule. Beginning with the First Crusade, which resulted in the conquest of Jerusalem in 1099, dozens of military campaigns were organised, providing a focal point of European history for centuries. Crusading declined rapidly after the 15th century. In 1095, Pope Urban II proclaimed the first expedition at the Council of Clermont. He encouraged military support for Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos and called for an armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Across all social strata in western Europe there was an enthusiastic response. Participants came from all over Europe and had a variety of motivations, including religious salvation, satisfying feudal obligations, opportunities for renown, and economic or political advantage.

15

Week 15: Monday, February 5, 2024

The Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire

WEEK 15

The two most important institutions of the Middle Ages in Europe were the Holy Catholic Church based in Rome and the Holy Roman Empire based in Germany or some other northern country. These two institutions were seen as extending back into past history to the days of Jesus of Nazareth. Both were seen to be eternal and universal. The truth was something different. The Holy Roman Empire was, as Voltaire remarked: "neither Holy nor Roman nor an Empire." But the mythology saw it as an extension of the real Roman Empire. The idea was that the Roman Empire had not declined and ended but had continued in the form of this newer "Holy Roman Empire" founded by Charlemagne and Pope Leo on Christmas Day in the year 800 AD. The Holy Catholic Church in Rome was on more solid ground. It most definitely was Roman. It was a church, an international church. And one would assume it was Holy. In the Medieval vision, these two institutions were partners in the leadership of the whole Christian world. Pope and Emperor, like Charlemagne and Pope Leo, were to work together to bring about peace and unity in the Christian world. In reality, the two fought most of the time. And the rare moments of complete amity between pope and emperor were brief and historically insignificant. But if the two institutions were competitors more than partners, they were, after all, the two institutions in the Middle Ages that mattered the most. This was especially true for Italy; more so for Italy than all the rest of Europe. One of the two institutions was based in the Italian city of Rome. And the second institution was led by the emperor who spent much of his time in Italy too. So whereas Englishmen might view both institutions as distant and unimportant, citizens of Italy most definitely did not.

RECOMMENDED READING

James Bryce,

The Holy Roman Empire,

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (September 12, 2012) ,

ISBN 1479208523

The Holy Roman Empire was, according to Voltaire, neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire. But it was long-lived, complex, brutal, important, and fascinating, as is evident from the reading of this notable work published in 1871 by the English jurist, historian and politician, James Bryce (1838 to 1922). Bryce concentrates his considerable erudition on the meaning and significance of the empire’s existence rather than on its chronology. This is an essential work for the understanding of western history.

Reader comments on Amazon:

By Lisa C. Philip on July 8, 2013 Format: Paperback." Even though this book was written over one hundred years ago it is still the best book on the topic. Packed with so much information. Highly recommended for anyone interested in the topic."

16

Week 16: Monday, February 12, 2024

The Universities

WEEK 16

One of the most important contributions to modern culture that comes from the Middle Ages are the universities. The ancient Greek and Roman world did not have universities. They had institutions of higher learning such as Plato's Academy, but they did not have universities. The name of the institution tells you much about what it proposed to do: universities were supposed to bring all knowledge together in one location with many different professors and students from all over the world, all of whom knew Latin, the language of a Medieval university. Two of the most important of the early universities were Italian: the University of Bologna specializing in Law, and the University of Padova (Padua in English) specializing in Medicine. We will discuss their creation and evolution and the role they played in the growth of Medieval Italy. In both Padova and Bologna, the university is the most important institution in the city and has significant political power and influence. A great university could MAKE a city; it could put it on the map! Thus any threat to withdraw and relocate was a potential catastrophe.

RECOMMENDED READING:

Charles Homer Haskins,

The Rise of the Universities ,

Cornell University Press Paperbacks, 1957 (First edition 1924),

ISBN 9780801490156

"The republication of Charles Homer Haskins' The Rise of Universities is cause for celebration among historians of higher education and among medievalists of all disciplines...Haskins' argument is a powerful one: that today's university system is a direct (and immediate) descendent of the collections of scholars who gathered around master teachers in the great cities of Europe during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries...[His] thesis was profound for its time and remains the guiding interpretation of medieval universities."

—Library Quarterly

See below the University of Bologna.

17

Week 17: Monday, February 19, 2024

The Cathedrals

WEEK 17

The great cathedrals of Europe are located in all the big cities in all European countries. They were constructed in the period between 1000 and 1400. The name of a "cathedral" rests on the presence of a bishop. The bishop's seat is the cathedra thus with a bishop in residence any Christian church becomes a cathedral: Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. Many great churches of Europe (Toulouse for example) are great examples of Medieval architecture but are not "cathedrals" due to the absence of a bishop. When we speak of a "cathedral" we usually mean a Medieval Gothic cathedrals. The greatest and largest Medieval Gothic cathedrals are located in the great capitals of Europe: Paris, York, Toledo, Milan Florence and Cologne. Paris created the "Gothic" cathedral. Paris invented Gothic architecture about 1150 with the construction of the church of Saint Denis in north Paris dedicated to the first great saint of Paris martyred in 250 AD Saint Denis. (The 19th century art historians invented the term "Gothic" for these cathedrals. It was an insult. They did not like Gothic. They liked the architecture of the Classical world: The Parthenon for example. So they invented a term to cast a cloud over the Gothic cathedrals.) Below see Notre Dame de Paris looking at the cathedral from the river on the south side.

18

Week 18: Monday, February 26, 2024

Art in the Middle Ages

WEEK 18

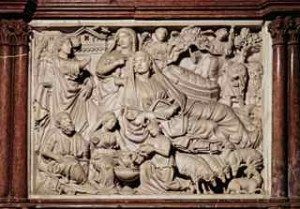

At the right you see Nicola Pisano, Nativiy, Carrara marble, Pisa Baptistry pulpit. Notice Mary and her Roman matron face. Pisano is copying Roman sculpture that is sitting there in Pisa. From 1000 AD to 1300 AD, artists in Europe changed the look of Western art. The change took place with Italian architects, sculptors and painters leading the way. The art of scuplture allows us to follow the transformation without interruption from the Fall of Rome all the way forward to our period, 1000-1300, this Winter Quarter. In Italy alone, there is no permanent interruption in the production of art even in the worst of times. In some periods the production is small, but it still allows us to see the change take place. Italy had one major advantage over other European states: it had the Roman scuptural past sitting all around it. Thus the first hints of Medieval artistic change are visible in cities such as Pisa where the Roman sculptural remains are rich, and local artists such as Nicola Pisano and his son Giovanni Pisano, can lead the way, starting with their own local Roman past. To the right, you see Pisano's Virgin Mary and she will remind you of a Roman matron.

19

Week 19: Monday, March 4, 2024

Saint Francis of Assisi

WEEK 19

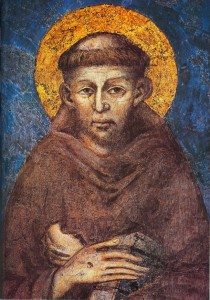

Saint Francis of Assisi (Italian: San Francesco d'Assisi; born Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, but nicknamed Francesco ("the Frenchman") by his father; 1181/1182 – October 3, 1226) was an Italian Catholic friar and preacher. He founded the men's Order of Friars Minor, the women’s Order of St. Clare, and the Third Order of Saint Francis for men and women not able to live the lives of itinerant preachers, followed by the early members of the Order of Friars Minor, or the monastic lives of the Poor Clares. Francis is one of the most venerated religious figures in history. Francis' father was Pietro di Bernardone, a prosperous silk merchant. Francis lived the high-spirited life typical of a wealthy young man, even fighting as a soldier for Assisi. While going off to war in 1204, Francis had a vision that directed him back to Assisi, where he lost his taste for his worldly life. On a pilgrimage to Rome, he joined the poor in begging at St. Peter's Basilica. The experience moved him to live in poverty. Francis returned home, began preaching on the streets, and soon gathered followers. His Order was authorized by Pope Innocent III in 1210. He then founded the Order of Poor Clares, which became an enclosed religious order for women, as well as the Order of Brothers and Sisters of Penance (commonly called the Third Order). In 1219, he went to Egypt in an attempt to convert the Sultan to put an end to the conflict of the Crusades. By this point, the Franciscan Order had grown to such an extent that its primitive organizational structure was no longer sufficient. He returned to Italy to organize the Order. Once his community was authorized by the Pope, he withdrew increasingly from external affairs. In 1223, Francis arranged for the first Christmas nativity scene. In 1224, he received the stigmata, making him the first recorded person to bear the wounds of Christ's Passion. He died during the evening hours of October 3, 1226, while listening to a reading he had requested of Psalm 142. On July 16, 1228, he was proclaimed a saint by Pope Gregory IX. He is known as the patron saint of animals and the environment, and is one of the two patron saints of Italy (with Catherine of Siena). It is customary for Catholic and Anglican churches to hold ceremonies blessing animals on his feast day of October 4. He is also known for his love of the Eucharist, his sorrow during the Stations of the Cross, and for the creation of the Christmas crèche or Nativity Scene.. (Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU

20

Week 20: Monday, March 11, 2024

Dante

WEEK 20

An introduction to Dante

The 13th century: commerce, urbanization, growth, and success

Italy in the 13th century: in the middle of the action

Florence: great success in the period from 1250 to 1300; introduction of the florin

Dante: 1265–1321

RECOMMENDED READING

The Mandelbaum translation is the best for our class. Its value is that it gives you an English and an Italian version on facing pages at a reasonable price.

Dante,

The Divine Comedy: Inferno,

translated by Allen Mandelbaum,

Bantam Classic,

ISBN 0553213393

Why choose this translation from among the 100's that exist? Read these comments:

Review "The English Dante of choice."--Hugh Kenner.

"Exactly what we have waited for these years, a Dante with clarity, eloquence, terror, and profoundly moving depths."--Robert Fagles, Princeton University

"Tough and supple, tender and violent . . . vigorous, vernacular . . . Mandelbaum's Dante will stand high among modern translations."--The Christian Science Monitor

"Lovers of the English language will be delighted by this eloquently accomplished enterprise." --Book Review Digest

From the Publisher: This splendid verse translation by Allen Mandelbaum provides an entirely fresh experience of Dante's great poem of penance and hope. As Dante ascends the Mount of Purgatory toward the Earthly Paradise and his beloved Beatrice, through "that second kingdom in which the human soul is cleansed of sin," all the passion and suffering, poetry and philosophy are rendered with the immediacy of a poet of our own age. With extensive notes and commentary prepared especially for this edition.

RECOMMENDED READING

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED: There is a good biography of Dante written by the late R. W. B. Lewis, Dante (ISBN 0670899097) and it is excellent and exactly what many of you will want: a short (200 pages), well-written, inexpensive ($19.95) biography of Dante. It is perfect for our course and although I don't want to make it a required book, I am sure that anyone who buys it will be happy they did.

All

Week 11: Mon., Jan. 8, 2024

Spain and Islam

WEEK 11

In 711, the armies of Islam crossed the Straits of Gibraltar and conquered almost all of Spain. This week we will discuss the impact Islam had on Spain and then all of Europe.

Islam is the monotheistic religion articulated by the Qur’an, a text considered by its adherents to be the verbatim word of God and by the teachings and normative example (called the Sunnah and composed of Hadith) of Muhammad, considered by them to be the last prophet of God. An adherent of Islam is called a Muslim. Muslims believe that God is one and incomparable and the purpose of existence is to worship God. Muslims also believe that Islam is the complete and universal version of a faith that was revealed at many times and places before, including through Abraham, Moses and Jesus, whom they consider prophets. They maintain that previous messages and revelations have been partially changed or corrupted over time, but consider the Qur'an to be both the unaltered and the final revelation of God. Religious concepts and practices include the five pillars of Islam, which are basic concepts and obligatory acts of worship, and following Islamic law, which touches on virtually every aspect of life and society, providing guidance on multifarious topics from banking and welfare, to warfare and the environment. The majority of Muslims are Sunni, being over 75-90% of all Muslims. The second largest sect, Shia, makes up 10-20%. About 13% of Muslims live in Indonesia, the largest Muslim country, 25% in South Asia, 20% in the Middle East, 2% in Central Asia, 4% in the remaining South East Asian countries, and 15% in Sub-saharan Africa. Sizable communities are also found in China and Russia, and parts of Europe. With over 1.5 billion followers or over 22% of earth's population as of 2009, Islam is the second-largest religion in the world.(Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING

Bernard Ellis Lewis,

Islam: The Religion and the People,

Pearson Prentice Hall; 1 edition (August 29, 2008),

ISBN 0132230852

Praise for Bernard Lewis:

"For newcomers to the subject, Bernard Lewis is the man." TIME Magazine

“The doyen of Middle Eastern studies." The New York Times

“No one writes about Muslim history with greater authority, or intelligence, or literary charm.” British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper.

If you would like to read one book for a general introduction to Islam written by a major European scholar then this book by Bernard Lewis is the best.

The book is in our Institute library.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE ACADEMIC YEAR

This new history of the Middles Ages has just appeared from the best-selling author Dan Jones. It is perfect for us. The organization and the coverage is excellent. It reads well and is a pleasure. The cost of it is about 20$ from Amazon, either hardcover or paperback. If you prefer the lighter paperback then choose it, but the hardcore will endure better. Please use our link on this page to buy from Amazon because we get credit($) for each purchase.

Here are just a few of the reviews.

"Not only an engrossing read about the distant past, both informative and entertaining, but also a profoundly thought-provoking view of our not-really-so-‘new’ present . . . All medieval history is here, beautifully narrated . . . The vision takes in whole imperial landscapes but also makes room for intimate portraits of key individuals, and even some poems."—Wall Street Journal

"A lively history . . . [Jones] has managed to touch every major topic. As each piece of the puzzle is placed into position, the modern world gradually comes into view . . . Powers and Thrones provides the reader with a framework for understanding a complicated subject, and it tells the story of an essential era of world history with skill and style."—The New York Times

The New York Times bestselling author returns with an epic history of the medieval world—a rich and complicated reappraisal of an era whose legacy and lessons we are still living with today.

Week 12: Mon., Jan. 15, 2024

Aquitaine

WEEK 12

Aquitaine is an historical region of southwestern France. It is situated in the southwest corner of France, along the Atlantic Ocean and the Pyrenees mountain range on the border with Spain, and for most of its written history Bordeaux has been a vital port and administrative center. There are traces of human settlement by prehistoric peoples, especially in the Périgord, but the earliest attested inhabitants in the south-west were the Aquitani, who were not considered Celtic people, but more akin to the Iberians (see Gallia Aquitania). The original Aquitania (named after the inhabitants) at the time of Caesar's conquest of Gaul included the area bounded by the river Garonne, the Pyrenees and the Atlantic Ocean. The name may stem from Latin 'aqua', maybe derived from a general geographical feature. In 392, the Roman imperial provinces were restructured as Aquitania Prima (north-east), Aquitania Secunda (centre) and Aquitania Tertia, better known as Novempopulania in the south-west. Accounts of Aquitania during the Early Middle Ages are imprecise, but there was much unrest. The Visigoths were called into Gaul as foederati, legalizing their status within the Empire. Eventually they established themselves as the de facto rulers in south-west Gaul as central Roman rule collapsed. Visigoths established their capital in Toulouse, but their tenure on Aquitaine was feeble. In 507, they were expelled south to Hispania after their defeat in the Battle of Vouillé by the Franks, who became the new rulers in the area to the south of the Loire. The Roman Aquitania Tertia remained in place, where a duke was appointed to hold a grip over the Basques (Vascones/Wascones, rendered Gascons in English). These dukes were quite detached from central Frankish overlordship, sometimes governing as independent rulers with strong ties to their kinsmen south of the Pyrenees. As of 660, the foundations for an independent Aquitaine/Vasconia polity were established by the duke Felix of Aquitaine, a magnate (potente(m)) from Toulouse, probably of Gallo-Roman stock. Despite its nominal submission to the Frankish Merovingians, the ethnic make-up of the new Aquitanian realm was not Frankish, but Gallo-Roman north of the Garonne and in main towns and Basque, especially south of the Garonne. In 721, the Aquitanian duke fended Umayyad troops (Sarracens) off at Toulouse, but in 732 the King of the Franks, Charles Martel led the effort to defeat the Islamic invaders at the Battle of Poitiers. In 781, Charlemagne decided to proclaim his son Louis King of Aquitaine within the Carolingian Empire, ruling over a realm comprising the Duchy of Aquitaine and the Duchy of Vasconia. He suppressed various Basque (Gascon) uprisings, even venturing into the lands of Pamplona past the Pyrenees after ravaging Gascony, with a view to imposing his authority also in the Vasconia to south of Pyrenees. According to his biography, he achieved everything he wanted and after staying overnight in Pamplona, on his way back his army was attacked in Roncevaux in 812, but narrowly escaped an engagement at the Pyrenean passes. Seguin (Sihiminus), count of Bordeaux and Duke of Vasconia, seemed to have attempted a detachment from the Frankish central authority on Charlemagne's death. The new emperor Louis the Pious reacted by removing him from his capacity, which stirred the Basques into rebellion. The king in turn sent his troops to the territory, obtaining their submission in two campaigns and killing the duke, while his family crossed the Pyrenees and continued to foment risings against Frankish power. In 824, the 2nd Battle of Roncevaux took place, in which counts Aeblus and Aznar, Frankish vassals from the Duchy of Vasconia sent by the new King of Aquitaine, Pepin, King of the Franks, were captured by the joint forces of Iñigo Arista and the Banu Qasi. Before Pepin's death, emperor Louis had appointed a new king in 832, his son Charles the Bald, while the Aquitanian lords elected Pepin II as king. This struggle for control of the kingdom led to a constant period of war between Charles, loyal to his father and the Carolingian power, and Pepin II, who relied more on the support of Basque and Aquitanian lords. Aquitaine after the Treaty of Verdun: After the 843 Treaty of Verdun, the defeat of Pepin II and the death of Charles the Bald, the Kingdom of Aquitaine (subsumed in West Francia) ceased to have any relevance and the title of King of Aquitaine took on a nominal value. In 1058, the Duchy of Vasconia (Gascony) and Aquitaine merged under the rule of William VIII, Duke of Aquitaine. Aquitaine passed to France in 1137 when the duchess Eleanor of Aquitaine married Louis VII of France, but their marriage was annulled in 1152. When Eleanor's new husband became King Henry II of England in 1154, the area became an English possession, and a cornerstone of the Angevin Empire. Aquitaine remained English until the end of the Hundred Years' War in 1453, when it was annexed by France. (Wikipedia)

Week 13: Mon., Jan. 22, 2024

Kings and Queens of Europe

WEEK 13

The Medieval monarch established order and unit within the chaos of the post-Roman Europe. The best example of how this worked was in England. England was a small kingdom, not much larger than some of the great duchies of France or Germany. An active king could visit most parts of his realm with some regularity. Moreover, a long series of conquests (especially 1066) had prevented the rise of strong provincial rulers or the development of deeply entrenched provincial institutions. Because no areas had been monopolized by provincial dynasties the king still had lands and rights of justice in all parts of his realm. Because his lands and rights were so widely dispersed he had to have agents everywhere —sheriffs and bailiffs, keepers of castles and forests. Keeping track of the income produced by hundreds of different sources made plain the need for a central financial office: the English Exchequer of the early 12th century. The Exchequer kept meticulously detailed records; it had a highly professional staff; it became so solidly established that it could function even in periods of civil war. Moreover, if all titles were based on grants or confirmation by the king, then it was natural that the king and his court would be asked to settle disputes over possession of land and the rights which went with land. "Court" is of course an ambiguous word; at first it meant no more than the great men—bishops, barons, and household officials—who were with the king. But even in the 11th century some of these men were more apt to be called on to deal with legal problems than others, and during the 12th century a group of royal justices appeared. Soon there were circuit judges, juries, writs. The new procedure of the royal courts was designed to cut down delay, to get quick, easily enforceable decisions in cases where decisions had been hard to reach. There was a deliberate attempt to reduce complicated problems to simple questions that could be answered by men with little knowledge of law or of remote events. Thus in cases involving land tenure the most common question was: "Who was last in peaceful possession?" not "Who has best title?" The question was answered by a group of neighbors, drawn from the law-abiding men of the district in which the property lay. They gave a collective response, based on their own knowledge and observations; there was no need for testimony and little opportunity for legal arguments. This procedure rapidly developed into trial by jury… an improvement on earlier, irrational procedures such as trial by combat or ordeals. In any case, knights, lesser landholders, and ordinary freemen in England found that the jury gave them some protection against the rich and the powerful. They flocked to the king's courts; by the 13th century all cases of any importance and significance whatever were heard by the king's judges. The royal government had succeeded in involving almost the entire free population of the country in the work of the law courts, either as litigants or as jurors. Local privileges and customs did not have time to harden into divisive institutions. The judicial and financial systems created in the 11th and 12th centuries could operate uniformly throughout the country. The king's justices, or even the king himself could give final judgments at once and anywhere. There was no need for elaborate individual negotiations with hundreds of lords and local communities when a tax was to be raised; the Council, and later the Parliament, could speak for the whole realm. Conversely, the English government could rely on unpaid local notables to do a great deal of the work of local administration. Energies which elsewhere were wasted in the defense of local privileges could be used in England to help the central government carry out its policies. If the English bureaucracy was inefficient, it was so at less cost than in other nascent states. Medieval states were law-states. They had acquired their power largely by developing their judicial institutions and by protecting the property rights of the possessing classes. A corollary of this emphasis on law was an emphasis on the right of consent. Existing usages, guaranteed by law, were a form of property and could not be changed without due process. Here is the background to the invention of Parliament: the principles that important decisions should be made publicly, that customs should not be changed without general agreement, that consent was necessary when the superior needed extraordinary additions to his income formed part of the general climate of opinion. These meetings, where important men of all classes came together, were convenient occasions for voicing grievances, for demanding investigations and reforms. All of this work of unifying the nation around functioning law courts was the conscious policy of King Henry II. He knew exactly what he was doing. His courts, often with his personal presence presiding, rendered fair justice. And the results of this justice was a united nation. It was exactly this unified nation that forced King John to sit down at the table and sign the most important Medieval document of them all: the Magna Carta. (some of the above text is taken from a very famous book by the historian Joseph Strayer, On the Medieval Origins of the Modern State (Princeton Classics, 21) Paperback.)

RECOMMENDED READING

Joseph Strayer,

On the Medieval Origins of the Modern State (Princeton Classics, 21),

Princeton University Press; Revised edition (March 29, 2016),

ISBN 978-0691169330

Week 14: Mon., Jan. 29, 2024

The Crusades

WEEK 14

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Christian Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these military expeditions are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were intended to reconquer Jerusalem and its surrounding area from Muslim rule. Beginning with the First Crusade, which resulted in the conquest of Jerusalem in 1099, dozens of military campaigns were organised, providing a focal point of European history for centuries. Crusading declined rapidly after the 15th century. In 1095, Pope Urban II proclaimed the first expedition at the Council of Clermont. He encouraged military support for Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos and called for an armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Across all social strata in western Europe there was an enthusiastic response. Participants came from all over Europe and had a variety of motivations, including religious salvation, satisfying feudal obligations, opportunities for renown, and economic or political advantage.

Week 15: Mon., Feb. 5, 2024

The Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire

WEEK 15

The two most important institutions of the Middle Ages in Europe were the Holy Catholic Church based in Rome and the Holy Roman Empire based in Germany or some other northern country. These two institutions were seen as extending back into past history to the days of Jesus of Nazareth. Both were seen to be eternal and universal. The truth was something different. The Holy Roman Empire was, as Voltaire remarked: "neither Holy nor Roman nor an Empire." But the mythology saw it as an extension of the real Roman Empire. The idea was that the Roman Empire had not declined and ended but had continued in the form of this newer "Holy Roman Empire" founded by Charlemagne and Pope Leo on Christmas Day in the year 800 AD. The Holy Catholic Church in Rome was on more solid ground. It most definitely was Roman. It was a church, an international church. And one would assume it was Holy. In the Medieval vision, these two institutions were partners in the leadership of the whole Christian world. Pope and Emperor, like Charlemagne and Pope Leo, were to work together to bring about peace and unity in the Christian world. In reality, the two fought most of the time. And the rare moments of complete amity between pope and emperor were brief and historically insignificant. But if the two institutions were competitors more than partners, they were, after all, the two institutions in the Middle Ages that mattered the most. This was especially true for Italy; more so for Italy than all the rest of Europe. One of the two institutions was based in the Italian city of Rome. And the second institution was led by the emperor who spent much of his time in Italy too. So whereas Englishmen might view both institutions as distant and unimportant, citizens of Italy most definitely did not.

RECOMMENDED READING

James Bryce,

The Holy Roman Empire,

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (September 12, 2012) ,

ISBN 1479208523

The Holy Roman Empire was, according to Voltaire, neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire. But it was long-lived, complex, brutal, important, and fascinating, as is evident from the reading of this notable work published in 1871 by the English jurist, historian and politician, James Bryce (1838 to 1922). Bryce concentrates his considerable erudition on the meaning and significance of the empire’s existence rather than on its chronology. This is an essential work for the understanding of western history.

Reader comments on Amazon:

By Lisa C. Philip on July 8, 2013 Format: Paperback." Even though this book was written over one hundred years ago it is still the best book on the topic. Packed with so much information. Highly recommended for anyone interested in the topic."

Week 16: Mon., Feb. 12, 2024

The Universities

WEEK 16

One of the most important contributions to modern culture that comes from the Middle Ages are the universities. The ancient Greek and Roman world did not have universities. They had institutions of higher learning such as Plato's Academy, but they did not have universities. The name of the institution tells you much about what it proposed to do: universities were supposed to bring all knowledge together in one location with many different professors and students from all over the world, all of whom knew Latin, the language of a Medieval university. Two of the most important of the early universities were Italian: the University of Bologna specializing in Law, and the University of Padova (Padua in English) specializing in Medicine. We will discuss their creation and evolution and the role they played in the growth of Medieval Italy. In both Padova and Bologna, the university is the most important institution in the city and has significant political power and influence. A great university could MAKE a city; it could put it on the map! Thus any threat to withdraw and relocate was a potential catastrophe.

RECOMMENDED READING:

Charles Homer Haskins,

The Rise of the Universities ,

Cornell University Press Paperbacks, 1957 (First edition 1924),

ISBN 9780801490156

"The republication of Charles Homer Haskins' The Rise of Universities is cause for celebration among historians of higher education and among medievalists of all disciplines...Haskins' argument is a powerful one: that today's university system is a direct (and immediate) descendent of the collections of scholars who gathered around master teachers in the great cities of Europe during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries...[His] thesis was profound for its time and remains the guiding interpretation of medieval universities."

—Library Quarterly

See below the University of Bologna.

Week 17: Mon., Feb. 19, 2024

The Cathedrals

WEEK 17

The great cathedrals of Europe are located in all the big cities in all European countries. They were constructed in the period between 1000 and 1400. The name of a "cathedral" rests on the presence of a bishop. The bishop's seat is the cathedra thus with a bishop in residence any Christian church becomes a cathedral: Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. Many great churches of Europe (Toulouse for example) are great examples of Medieval architecture but are not "cathedrals" due to the absence of a bishop. When we speak of a "cathedral" we usually mean a Medieval Gothic cathedrals. The greatest and largest Medieval Gothic cathedrals are located in the great capitals of Europe: Paris, York, Toledo, Milan Florence and Cologne. Paris created the "Gothic" cathedral. Paris invented Gothic architecture about 1150 with the construction of the church of Saint Denis in north Paris dedicated to the first great saint of Paris martyred in 250 AD Saint Denis. (The 19th century art historians invented the term "Gothic" for these cathedrals. It was an insult. They did not like Gothic. They liked the architecture of the Classical world: The Parthenon for example. So they invented a term to cast a cloud over the Gothic cathedrals.) Below see Notre Dame de Paris looking at the cathedral from the river on the south side.

Week 18: Mon., Feb. 26, 2024

Art in the Middle Ages

WEEK 18

At the right you see Nicola Pisano, Nativiy, Carrara marble, Pisa Baptistry pulpit. Notice Mary and her Roman matron face. Pisano is copying Roman sculpture that is sitting there in Pisa. From 1000 AD to 1300 AD, artists in Europe changed the look of Western art. The change took place with Italian architects, sculptors and painters leading the way. The art of scuplture allows us to follow the transformation without interruption from the Fall of Rome all the way forward to our period, 1000-1300, this Winter Quarter. In Italy alone, there is no permanent interruption in the production of art even in the worst of times. In some periods the production is small, but it still allows us to see the change take place. Italy had one major advantage over other European states: it had the Roman scuptural past sitting all around it. Thus the first hints of Medieval artistic change are visible in cities such as Pisa where the Roman sculptural remains are rich, and local artists such as Nicola Pisano and his son Giovanni Pisano, can lead the way, starting with their own local Roman past. To the right, you see Pisano's Virgin Mary and she will remind you of a Roman matron.

Week 19: Mon., Mar. 4, 2024

Saint Francis of Assisi

WEEK 19

Saint Francis of Assisi (Italian: San Francesco d'Assisi; born Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, but nicknamed Francesco ("the Frenchman") by his father; 1181/1182 – October 3, 1226) was an Italian Catholic friar and preacher. He founded the men's Order of Friars Minor, the women’s Order of St. Clare, and the Third Order of Saint Francis for men and women not able to live the lives of itinerant preachers, followed by the early members of the Order of Friars Minor, or the monastic lives of the Poor Clares. Francis is one of the most venerated religious figures in history. Francis' father was Pietro di Bernardone, a prosperous silk merchant. Francis lived the high-spirited life typical of a wealthy young man, even fighting as a soldier for Assisi. While going off to war in 1204, Francis had a vision that directed him back to Assisi, where he lost his taste for his worldly life. On a pilgrimage to Rome, he joined the poor in begging at St. Peter's Basilica. The experience moved him to live in poverty. Francis returned home, began preaching on the streets, and soon gathered followers. His Order was authorized by Pope Innocent III in 1210. He then founded the Order of Poor Clares, which became an enclosed religious order for women, as well as the Order of Brothers and Sisters of Penance (commonly called the Third Order). In 1219, he went to Egypt in an attempt to convert the Sultan to put an end to the conflict of the Crusades. By this point, the Franciscan Order had grown to such an extent that its primitive organizational structure was no longer sufficient. He returned to Italy to organize the Order. Once his community was authorized by the Pope, he withdrew increasingly from external affairs. In 1223, Francis arranged for the first Christmas nativity scene. In 1224, he received the stigmata, making him the first recorded person to bear the wounds of Christ's Passion. He died during the evening hours of October 3, 1226, while listening to a reading he had requested of Psalm 142. On July 16, 1228, he was proclaimed a saint by Pope Gregory IX. He is known as the patron saint of animals and the environment, and is one of the two patron saints of Italy (with Catherine of Siena). It is customary for Catholic and Anglican churches to hold ceremonies blessing animals on his feast day of October 4. He is also known for his love of the Eucharist, his sorrow during the Stations of the Cross, and for the creation of the Christmas crèche or Nativity Scene.. (Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING

Ferdinand Schevill,

Medieval and Renaissance Florence,

Harper Torchbook paperback, 1963, 2 volumes,

ISBN B000PX4SUU

Week 20: Mon., Mar. 11, 2024

Dante

WEEK 20

An introduction to Dante

The 13th century: commerce, urbanization, growth, and success

Italy in the 13th century: in the middle of the action

Florence: great success in the period from 1250 to 1300; introduction of the florin

Dante: 1265–1321

RECOMMENDED READING

The Mandelbaum translation is the best for our class. Its value is that it gives you an English and an Italian version on facing pages at a reasonable price.

Dante,

The Divine Comedy: Inferno,

translated by Allen Mandelbaum,

Bantam Classic,

ISBN 0553213393

Why choose this translation from among the 100's that exist? Read these comments:

Review "The English Dante of choice."--Hugh Kenner.

"Exactly what we have waited for these years, a Dante with clarity, eloquence, terror, and profoundly moving depths."--Robert Fagles, Princeton University

"Tough and supple, tender and violent . . . vigorous, vernacular . . . Mandelbaum's Dante will stand high among modern translations."--The Christian Science Monitor

"Lovers of the English language will be delighted by this eloquently accomplished enterprise." --Book Review Digest

From the Publisher: This splendid verse translation by Allen Mandelbaum provides an entirely fresh experience of Dante's great poem of penance and hope. As Dante ascends the Mount of Purgatory toward the Earthly Paradise and his beloved Beatrice, through "that second kingdom in which the human soul is cleansed of sin," all the passion and suffering, poetry and philosophy are rendered with the immediacy of a poet of our own age. With extensive notes and commentary prepared especially for this edition.

RECOMMENDED READING

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED: There is a good biography of Dante written by the late R. W. B. Lewis, Dante (ISBN 0670899097) and it is excellent and exactly what many of you will want: a short (200 pages), well-written, inexpensive ($19.95) biography of Dante. It is perfect for our course and although I don't want to make it a required book, I am sure that anyone who buys it will be happy they did.