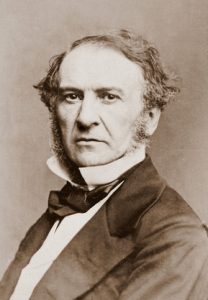

"Gladstone never envisaged a social order in which the landed aristocracy would not be the governing class, but he believed profoundly in the need for that class to be imbued with the earnestness, the moral purity, the readiness for hard work which, in his eyes, characterized the best elements of the non-conformist middle class." —Robert Blake

"Disraeli began as an outsider, a forerunner of Wilde, Proust, Waugh, fascinated by the aristocracy, half in love with it, half mocking it, an amusing young artist, the inventor of the political novel, a brilliant talker and diner-out, thought of as something of a bounder by men, and found attractive by women…. He was a romantic, a believer in dark, irrational forces and men of genius. Art, love, passion, the mystical elements of religion, meant more to him than railways or the transforming discoveries of the natural sciences, or the industrial might of England, or social improvement, or any truth obtained by measurement, statistics, deduction…. His entire life was a sustained attempt to live a fiction, and to cast its spell over the minds of others." —Isaiah Berlin Prof. Bruce Thompson on Gladstone and Disraili:

MIGHTY OPPOSITES

"The two great Prime Ministers of the nineteenth century in Britain, Benjamin Disraeli and William Ewart Gladstone, could not have been more different from each other. Gladstone, the Liberal, had a powerful religious conscience; Disraeli, the Tory, born Jewish but baptized, had no religious feelings at all. Disraeli wrote romantic novels about the need for building bridges between the classes; Gladstone, an Oxford-trained classicist, occupied himself with a three-volume work in which he tried to prove that Homer had anticipated the Christian doctrine of the Trinity. Disraeli dressed and spoke like a dandy, had numerous love affairs, and piled up debts; Gladstone had a well-deserved reputation for financial probity and rigorous morality. In politics, Disraeli was an opportunist, Gladstone a man of conviction. Disraeli began his career by splitting the Conservative Party over the issue of the Corn Laws, bringing down Sir Robert Peel. Gladstone ended his career by splitting the Liberal Party over the issue of Home Rule for Ireland. Both sent their parties into the political wilderness for the better part of two decades, but Disraeli did so to enhance his own power, while Gladstone did so as a matter of conscience. Disraeli, says his biographer Robert Blake, "alternated between Queen Victoria's view that Gladstone was insane and the more common Tory theory that he was a monstrous hypocrite." He damned Gladstone as a "sophisticated rhetorician intoxicated with the exuberance of his own verbosity." Another contemporary: "I don't object to Gladstone always having the ace of trumps up his sleeve, but merely to his belief that the Almighty put it there." Disraeli, on the other hand, was a great actor on the public stage, watching his own performance and that of others with ironic detachment. His only genuine emotion in politics, the great historian A.J.P. Taylor has suggested (unfairly?), sprang from personal dislike—of Peel in his early career, and of Gladstone, more strongly, towards the end."

RECOMMENDED READING

David Cannadine,

Victorious Century: The United Kingdom, 1800-1906,

Viking (February 20, 2018),

ISBN 052555789X

James S., Jr. Donnelly,

The Great Irish Potato Famine,

The History Press (September 1, 2008),

ISBN 0750929286