Week 11

Week 11: Tuesday, January 7, 2025

Andrew Johnson

Week 11

Andrew Johnson (1808 – 1875) was an American politician who served as the 17th president of the United States from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, as he was vice president at that time. Johnson was a Democrat who ran with Abraham Lincoln on the National Union Party ticket, coming to office as the Civil War concluded. He favored quick restoration of the seceded states to the Union without protection for the newly freed people who were formerly enslaved. This led to conflict with the Republican-dominated Congress, culminating in his impeachment by the House of Representatives in 1868. He was acquitted in the Senate by one vote. Johnson was born into poverty and never attended school. He was apprenticed as a tailor and worked in several frontier towns before settling in Greeneville, Tennessee, serving as an alderman and mayor before being elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives in 1835. After briefly serving in the Tennessee Senate, Johnson was elected to the House of Representatives in 1843, where he served five two-year terms. He became governor of Tennessee for four years, and was elected by the legislature to the Senate in 1857. During his congressional service, he sought passage of the Homestead Bill which was enacted soon after he left his Senate seat in 1862. Southern slave states seceded to form the Confederate States of America, including Tennessee, but Johnson remained firmly with the Union. He was the only sitting senator from a Confederate state who did not resign his seat upon learning of his state's secession. In 1862, Lincoln appointed him as Military Governor of Tennessee after most of it had been retaken. In 1864, Johnson was a logical choice as running mate for Lincoln, who wished to send a message of national unity in his re-election campaign, and became vice president after a victorious election in 1864. Johnson implemented his own form of Presidential Reconstruction, a series of proclamations directing the seceded states to hold conventions and elections to reform their civil governments. Southern states returned many of their old leaders and passed Black Codes to deprive the freedmen of many civil liberties, but Congressional Republicans refused to seat legislators from those states and advanced legislation to overrule the Southern actions. Johnson vetoed their bills, and Congressional Republicans overrode him, setting a pattern for the remainder of his presidency.[b] Johnson opposed the Fourteenth Amendment which gave citizenship to former slaves. In 1866, he went on an unprecedented national tour promoting his executive policies, seeking to break Republican opposition.[5] As the conflict grew between the branches of government, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act restricting Johnson's ability to fire Cabinet officials. He persisted in trying to dismiss Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, but ended up being impeached by the House of Representatives and narrowly avoided conviction in the Senate. He did not win the 1868 Democratic presidential nomination and left office the following year. (Wikipedia)

Andrew Johnson (1808 – 1875) was an American politician who served as the 17th president of the United States from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, as he was vice president at that time. Johnson was a Democrat who ran with Abraham Lincoln on the National Union Party ticket, coming to office as the Civil War concluded. He favored quick restoration of the seceded states to the Union without protection for the newly freed people who were formerly enslaved. This led to conflict with the Republican-dominated Congress, culminating in his impeachment by the House of Representatives in 1868. He was acquitted in the Senate by one vote. Johnson was born into poverty and never attended school. He was apprenticed as a tailor and worked in several frontier towns before settling in Greeneville, Tennessee, serving as an alderman and mayor before being elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives in 1835. After briefly serving in the Tennessee Senate, Johnson was elected to the House of Representatives in 1843, where he served five two-year terms. He became governor of Tennessee for four years, and was elected by the legislature to the Senate in 1857. During his congressional service, he sought passage of the Homestead Bill which was enacted soon after he left his Senate seat in 1862. Southern slave states seceded to form the Confederate States of America, including Tennessee, but Johnson remained firmly with the Union. He was the only sitting senator from a Confederate state who did not resign his seat upon learning of his state's secession. In 1862, Lincoln appointed him as Military Governor of Tennessee after most of it had been retaken. In 1864, Johnson was a logical choice as running mate for Lincoln, who wished to send a message of national unity in his re-election campaign, and became vice president after a victorious election in 1864. Johnson implemented his own form of Presidential Reconstruction, a series of proclamations directing the seceded states to hold conventions and elections to reform their civil governments. Southern states returned many of their old leaders and passed Black Codes to deprive the freedmen of many civil liberties, but Congressional Republicans refused to seat legislators from those states and advanced legislation to overrule the Southern actions. Johnson vetoed their bills, and Congressional Republicans overrode him, setting a pattern for the remainder of his presidency.[b] Johnson opposed the Fourteenth Amendment which gave citizenship to former slaves. In 1866, he went on an unprecedented national tour promoting his executive policies, seeking to break Republican opposition.[5] As the conflict grew between the branches of government, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act restricting Johnson's ability to fire Cabinet officials. He persisted in trying to dismiss Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, but ended up being impeached by the House of Representatives and narrowly avoided conviction in the Senate. He did not win the 1868 Democratic presidential nomination and left office the following year. (Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

From the Publisher:

"For too long we’ve lacked a compact, inexpensive, authoritative, and compulsively readable book that offers American readers a clear, informative, and inspiring narrative account of their country. Such a fresh retelling of the American story is especially needed today, to shape and deepen young Americans’ sense of the land they inhabit, help them to understand its roots and share in its memories, all the while equipping them for the privileges and responsibilities of citizenship in American society. The existing texts simply fail to tell that story with energy and conviction. Too often they reflect a fragmented outlook that fails to convey to American readers the grand trajectory of their own history. A great nation needs and deserves a great and coherent narrative, as an expression of its own self-understanding and its aspirations; and it needs to be able to convey that narrative effectively. Of course, it goes without saying that such a narrative cannot be a fairy tale of the past. It will not be convincing if it is not truthful. But as Land of Hope brilliantly shows, there is no contradiction between a truthful account of the American past and an inspiring one. Readers of Land of Hope will find both in its pages."

REVIEWS

“At a time of severe partisanship that has infected many accounts of our nation’s past, this brilliant new history, Land of Hope, written in lucid and often lyrical prose, is much needed. It is accurate, honest, and free of the unhistorical condescension so often paid to the people of America’s past. This generous but not uncritical story of our nation’s history ought to be read by every American. It explains and justifies the right kind of patriotism.”― Gordon S. Wood, author of Friends Divided: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson

“We’ve long needed a readable text that truly tells the American story, neither hiding the serious injustices in our history nor soft-pedaling our nation’s extraordinary achievements. Such a text cannot be a mere compilation of facts, and it certainly could not be written by someone lacking a deep understanding and appreciation of America’s constitutional ideals and institutions. Bringing his impressive skills as a political theorist, historian, and writer to bear, Wilfred McClay has supplied the need.”― Robert P. George, McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence, Princeton University

“No one has told the story of America with greater balance or better prose than Wilfred McClay. Land of Hope is a history book that you will not be able to put down. From the moment that ‘natives’ first crossed here over the Bering Strait, to the founding of America’s great experiment in republican government, to the horror and triumph of the Civil War...McClay’s account will capture your attention while offering an unforgettable education.”― James W. Ceaser, Professor of Politics, University of Virginia

12

Week 12: Tuesday, January 14, 2025

Ulysses S. Grant

Week 12

Ulysses S. Grant (1822 – 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As commanding general, Grant led the Union Army to victory in the American Civil War in 1865 and briefly served as U.S. secretary of war. An effective civil rights executive, Grant signed a bill to create the Justice Department and worked with Radical Republicans to protect African Americans during Reconstruction. Grant was born in Ohio and graduated from West Point in 1843. He served with distinction in the Mexican–American War, but resigned from the army in 1854 and returned to civilian life impoverished. In 1861, shortly after the Civil War began, Grant joined the Union Army and rose to prominence after securing Union victories in the western theater. In 1863, he led the Vicksburg campaign that gave Union forces control of the Mississippi River and dealt a major strategic blow to the Confederacy. President Abraham Lincoln promoted Grant to lieutenant general after his victory at Chattanooga. For thirteen months, Grant fought Robert E. Lee during the high-casualty Overland Campaign which ended with capture of Lee's army at Appomattox, where he formally surrendered to Grant. In 1866, President Andrew Johnson promoted Grant to General of the Army. Later, Grant broke with Johnson over Reconstruction policies. A war hero, drawn in by his sense of duty, Grant was unanimously nominated by the Republican Party and then elected president in 1868. As president, Grant stabilized the post-war national economy, supported congressional Reconstruction and the Fifteenth Amendment, and prosecuted the Ku Klux Klan. Under Grant, the Union was completely restored. He appointed African Americans and Jewish Americans to prominent federal offices. In 1871, he created the first Civil Service Commission, advancing the civil service more than any prior president. Grant was re-elected in the 1872 presidential election, but was inundated by executive scandals during his second term. His response to the Panic of 1873 was ineffective in halting the Long Depression, which contributed to the Democrats winning the House majority in 1874. Grant's Native American policy was to assimilate Indians into Anglo-American culture. In Grant's foreign policy, the Alabama Claims against Britain were peacefully resolved, but the Senate rejected Grant's annexation of Santo Domingo. In the disputed 1876 presidential election, Grant facilitated the approval by Congress of a peaceful compromise. Leaving office in 1877, Grant undertook a world tour, meeting prominent figures and becoming the first president to circumnavigate the world. In 1880, he was unsuccessful in obtaining the Republican nomination for a third term. In 1885, facing severe financial reversals and dying of throat cancer, Grant wrote his memoirs, covering his life through the Civil War, which were posthumously published and became a major critical and financial success. At his death, Grant was the most popular American and was memorialized as a symbol of national unity. Due to the Lost Cause myth spread by Confederate sympathizers around the turn of the 20th century, historical assessments and rankings of Grant's presidency suffered considerably before they began recovering in the 21st century. Grant's critics take a negative view of his economic mismanagement and the corruption within his administration, while his admirers emphasize his policy towards Native Americans, vigorous enforcement of civil and voting rights for African Americans, and securing North and South as a single nation within the Union. (Wikipedia)

Ulysses S. Grant (1822 – 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As commanding general, Grant led the Union Army to victory in the American Civil War in 1865 and briefly served as U.S. secretary of war. An effective civil rights executive, Grant signed a bill to create the Justice Department and worked with Radical Republicans to protect African Americans during Reconstruction. Grant was born in Ohio and graduated from West Point in 1843. He served with distinction in the Mexican–American War, but resigned from the army in 1854 and returned to civilian life impoverished. In 1861, shortly after the Civil War began, Grant joined the Union Army and rose to prominence after securing Union victories in the western theater. In 1863, he led the Vicksburg campaign that gave Union forces control of the Mississippi River and dealt a major strategic blow to the Confederacy. President Abraham Lincoln promoted Grant to lieutenant general after his victory at Chattanooga. For thirteen months, Grant fought Robert E. Lee during the high-casualty Overland Campaign which ended with capture of Lee's army at Appomattox, where he formally surrendered to Grant. In 1866, President Andrew Johnson promoted Grant to General of the Army. Later, Grant broke with Johnson over Reconstruction policies. A war hero, drawn in by his sense of duty, Grant was unanimously nominated by the Republican Party and then elected president in 1868. As president, Grant stabilized the post-war national economy, supported congressional Reconstruction and the Fifteenth Amendment, and prosecuted the Ku Klux Klan. Under Grant, the Union was completely restored. He appointed African Americans and Jewish Americans to prominent federal offices. In 1871, he created the first Civil Service Commission, advancing the civil service more than any prior president. Grant was re-elected in the 1872 presidential election, but was inundated by executive scandals during his second term. His response to the Panic of 1873 was ineffective in halting the Long Depression, which contributed to the Democrats winning the House majority in 1874. Grant's Native American policy was to assimilate Indians into Anglo-American culture. In Grant's foreign policy, the Alabama Claims against Britain were peacefully resolved, but the Senate rejected Grant's annexation of Santo Domingo. In the disputed 1876 presidential election, Grant facilitated the approval by Congress of a peaceful compromise. Leaving office in 1877, Grant undertook a world tour, meeting prominent figures and becoming the first president to circumnavigate the world. In 1880, he was unsuccessful in obtaining the Republican nomination for a third term. In 1885, facing severe financial reversals and dying of throat cancer, Grant wrote his memoirs, covering his life through the Civil War, which were posthumously published and became a major critical and financial success. At his death, Grant was the most popular American and was memorialized as a symbol of national unity. Due to the Lost Cause myth spread by Confederate sympathizers around the turn of the 20th century, historical assessments and rankings of Grant's presidency suffered considerably before they began recovering in the 21st century. Grant's critics take a negative view of his economic mismanagement and the corruption within his administration, while his admirers emphasize his policy towards Native Americans, vigorous enforcement of civil and voting rights for African Americans, and securing North and South as a single nation within the Union. (Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING

13

Week 13: Tuesday, January 21, 2025

President Grant

Week 13

"What a man he is! what a history! what an illustration—his life—of the capacities of that American individuality common to us all. Cynical critics are wondering “what the people can see in Grant” to make such a hubbub about. They aver . . . that he has hardly the average of our day’s literary and scholastic culture, and absolutely no pronounc’d genius or conventional eminence of any sort. Correct: but he proves how an average western farmer, mechanic, boatman, carried by tides of circumstances, perhaps caprices, into a position of incredible military or civil responsibilities . . . may steer his way fitly and steadily through them all, carrying the country and himself with credit year after year—command over a million armed men—fight more than fifty pitch’d battles—rule for eight years a land larger than all the kingdoms of Europe combined—and then, retiring, quietly (with a cigar in his mouth) make the promenade of the whole world, through its courts and coteries, and kings and czars and mikados . . . as phlegmatically as he ever walk’d the portico of a Missouri hotel after dinner . . . Seems to me it transcends Plutarch. How those old Greeks, indeed, would have seized on him! A mere plain man—no art, no poetry . . . A common trader, money-maker, tanner, farmer of Illinois—general for the republic . . . in the war of attempted secession—President following, (a task of peace, more difficult than the war itself)—nothing heroic, as the authorities put it—and yet the greatest hero. The gods, the destinies, seem to have concentrated upon him." WALT WHITMAN, Specimen Days

"What a man he is! what a history! what an illustration—his life—of the capacities of that American individuality common to us all. Cynical critics are wondering “what the people can see in Grant” to make such a hubbub about. They aver . . . that he has hardly the average of our day’s literary and scholastic culture, and absolutely no pronounc’d genius or conventional eminence of any sort. Correct: but he proves how an average western farmer, mechanic, boatman, carried by tides of circumstances, perhaps caprices, into a position of incredible military or civil responsibilities . . . may steer his way fitly and steadily through them all, carrying the country and himself with credit year after year—command over a million armed men—fight more than fifty pitch’d battles—rule for eight years a land larger than all the kingdoms of Europe combined—and then, retiring, quietly (with a cigar in his mouth) make the promenade of the whole world, through its courts and coteries, and kings and czars and mikados . . . as phlegmatically as he ever walk’d the portico of a Missouri hotel after dinner . . . Seems to me it transcends Plutarch. How those old Greeks, indeed, would have seized on him! A mere plain man—no art, no poetry . . . A common trader, money-maker, tanner, farmer of Illinois—general for the republic . . . in the war of attempted secession—President following, (a task of peace, more difficult than the war itself)—nothing heroic, as the authorities put it—and yet the greatest hero. The gods, the destinies, seem to have concentrated upon him." WALT WHITMAN, Specimen Days

RECOMMENDED READING

Review

“This is a good time for Ron Chernow’s fine biography of Ulysses S. Grant to appear . . . As history, it is remarkable, full of fascinating details sure to make it interesting both to those with the most cursory knowledge of Grant’s life and to those who have read his memoirs or any of several previous biographies . . . For all its scholarly and literary strengths, this book’s greatest service is to remind us of Grant’s significant achievements at the end of the war and after, which have too long been overlooked and are too important today to be left in the dark . . . As Americans continue the struggle to defend justice and equality in our tumultuous and divisive era, we need to know what Grant did when our country’s very existence hung in the balance. If we still believe in forming a more perfect union, his steady and courageous example is more valuable than ever.” —Bill Clinton, New York Times Book Review

“Grant is vast and panoramic in ways that history buffs will love. Books of its caliber by writers of Chernow’s stature are rare, and this one qualifies as a major event . . . . Chernow is clearly out to find undiscovered nobility in his story, and he succeeds; he also finds uncannily prescient tragedy. There are ways in which Grant’s times eerily resemble our own . . . Indispensable.” —The New York Times

“Marvelous . . . Chernow’s biography gives us a deep look into this complicated but straightforward man, and into a troubled time in our history that still echoes today.” —Thomas E. Ricks, Foreign Policy

“A triumph: a sympathetic but clear-eyed biography that will be the starting point for all future studies of this enigmatic man . . . Chernow [is] one of the finest biographical writers in American history.” —Foreign Affairs

“Arriving at a moment when excitable individuals and hysterical mobs are demonstrating crudeness in assessing historical figures, Chernow’s book is a tutorial on measured, mature judgment . . . Chernow’s ‘Grant’ is a gift to a nation much in need of measured judgments about its past.” —George Will, The Washington Post

“Chernow’s Grant is as relevant a modern figure as his Hamilton. His Grant is a reminder that the very best American leaders can be, and should be, self-made, hard-working, modest for themselves and ambitious for their nation, future-looking, tolerant, and with a heart for the poor . . . . Chernow turns the life of yet another misunderstood figure from U.S. currency into narrative gold.” —Slate

“Chernow’s special gift is to present a complete and compelling picture of his subjects. His biographies do not offer up marble deities on a pedestal; he gives us flesh and blood human beings and helps us understand what made them tick. Just as he did with George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, Chernow brings Ulysses S. Grant to life. At the end of the book, the reader feels as if he knows the man . . . A magnificent book . . . This is richly rewarding and compelling reading.” —Christian Science Monitor

“In 1948, a survey of historians ranked Ulysses S. Grant as the second-worst American president. Corruption had badly tarred his administration, just as it had that of the man at the bottom, Warren Harding. But recent surveys have been kinder. Grant now lands in the middle, thanks to his extraordinarily progressive work on race relations . . . . Ron Chernow’s 1,100-page biography may crown Grant’s restoration . . . . Mr. Chernow argues persuasively that Grant has been badly misunderstood.” —The Economist

“A landmark work . . . . Chernow impressively examines Grant’s sensitivities and complexities and helps us to better understand an underappreciated man and underrated president who served his country extraordinarily well . . . . monumental and gripping . . . in every respect, which even at nearly 1,000 pages, is not a sentence too long." —American Scholar

“Reading Ron Chernow's new biography, a truly mammoth examination of the life of Ulysses S. Grant, one is struck by the humanity—both the pitiful frailty and the incredible strength—of its subject.” —Philadelphia Inquirer

“Masterful and often poignant . . . Chernow's gracefully written biography, which promises to be the definitive work on Grant for years to come, is fully equal to the man's remarkable story.” —Minneapolis Star Tribune

“Reading this compelling book, it’s hard to imagine that we’ll continue to define Grant by these scandals rather than all he accomplished in winning the war and doing his best to make peace, on inclusive terms that would be fair to all.” —Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

“[A] beautifully written portrait . . . . Chernow doesn’t gloss over Grant’s struggle with alcoholism or his tendency to trust shady operators. However, his willingness to protect the gains of freemen and to fight the KKK was an example of the moral courage he consistently displayed. This is a superb tribute to Grant, whose greatness is earning increased appreciation.” —Booklist, Starred Review

“A stupendous new biography . . . Fascinating and immensely readable . . . uncommonly compelling and timely . . . . Chernow’s biography is replete with fascinating details and insightful political analysis, a combination that brings Grant and his time to life . . . put Grant on your must-read list.” —BookPage

14

Week 14: Tuesday, January 28, 2025

Uniting the Nation: The Railroads

Week 14

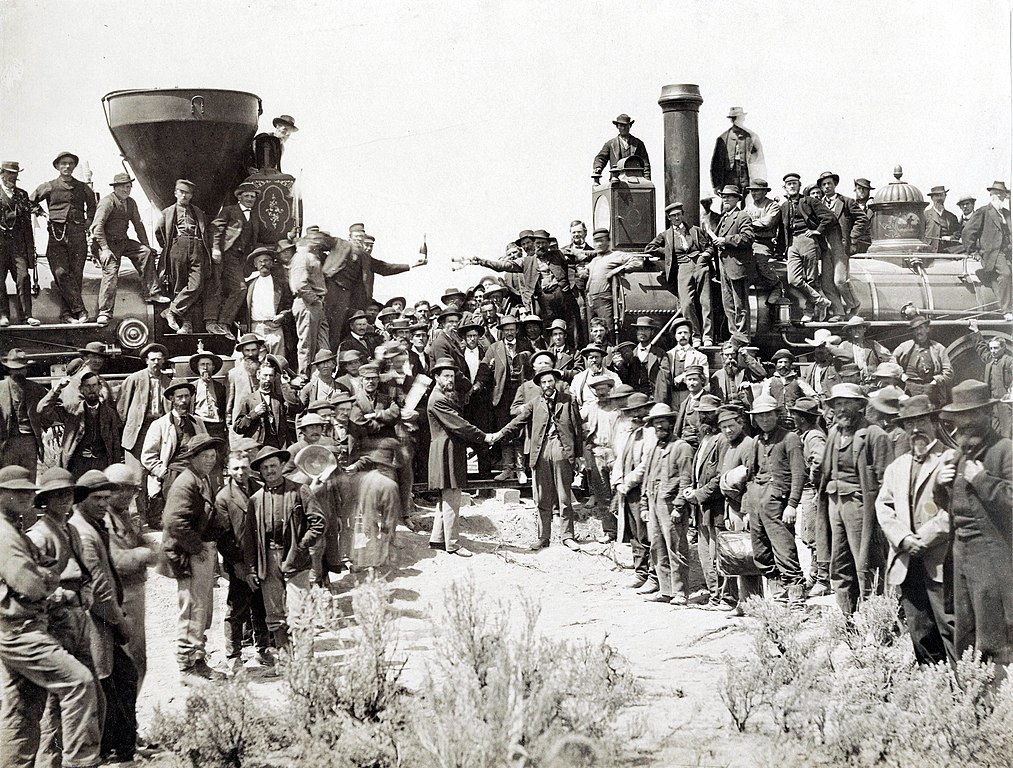

America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the "Overland Route") was a 1,911-mile continuous railroad line built between 1863 and 1869 that connected the existing eastern U.S. rail network at Council Bluffs, Iowa, with the Pacific coast at the Oakland Long Wharf on San Francisco Bay. The rail line was built by three private companies over public lands provided by extensive U.S. land grants. Building was financed by both state and U.S. government subsidy bonds as well as by company-issued mortgage bonds. The Western Pacific Railroad Company built 132 miles of track from the road's western terminus at Alameda/Oakland to Sacramento, California. The Central Pacific Railroad Company of California (CPRR) constructed 690 miles east from Sacramento to Promontory Summit, Utah Territory. The Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) built 1,085 miles from the road's eastern terminus at the Missouri River settlements of Council Bluffs and Omaha, Nebraska, westward to Promontory Summit. The railroad opened for through traffic between Sacramento and Omaha on May 10, 1869, when CPRR President Leland Stanford ceremonially tapped the gold "Last Spike" (later often referred to as the "Golden Spike") with a silver hammer at Promontory Summit. In the following six months, the last leg from Sacramento to San Francisco Bay was completed. The resulting coast-to-coast railroad connection revolutionized the settlement and economy of the American West. It brought the western states and territories into alignment with the northern Union states and made transporting passengers and goods coast-to-coast considerably quicker, safer and less expensive. The first transcontinental rail passengers arrived at the Pacific Railroad's original western terminus at the Alameda Terminal on September 6, 1869, where they transferred to the steamer Alameda for transport across the Bay to San Francisco. The road's rail terminus was moved two months later to the Oakland Long Wharf, about a mile to the north, when its expansion was completed and opened for passengers on November 8, 1869. Service between San Francisco and Oakland Pier continued to be provided by ferry. The CPRR eventually purchased 53 miles (85 km) of UPRR-built grade from Promontory Summit (MP 828) to Ogden, Utah Territory (MP 881), which became the interchange point between trains of the two roads. (Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING

Stephen E. Ambrose,

Nothing Like It In the World: The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad 1863-1869,

Simon & Schuster,

ISBN 978-0743203173

15

Week 15: Tuesday, February 4, 2025

The Homestead Acts

Week 15

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, typically called a homestead. In all, more than 160 million acres of public land, or nearly 10 percent of the total area of the United States, was given away free to 1.6 million homesteaders; most of the homesteads were west of the Mississippi River. These acts were the first sovereign decisions of post-war North–South capitalist cooperation in the United States. An extension of the homestead principle in law, the Homestead Acts were an expression of the Free Soil policy of Northerners who wanted individual farmers to own and operate their own farms, as opposed to Southern slave owners who wanted to buy up large tracts of land and use slave labor, thereby shutting out free white farmers. For a number of years individual Congressmen put forward bills providing for homesteading, but it wasn't until 1862 that the first homestead act was passed. The Homestead Act of 1862 opened up millions of acres. Any adult who had never taken up arms against the federal government of the United States could apply. Women and immigrants who had applied for citizenship were eligible. Several additional laws were enacted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Southern Homestead Act of 1866 sought to address land ownership inequalities in the south during Reconstruction. It explicitly included Black Americans and encouraged them to participate, and, although rampant discrimination, systemic barriers, and bureaucratic inertia considerably slowed Black gains, the 1866 law was part of the reason that within a generation after its passage, by 1900, one quarter of all Southern Black farmers were farm owners. (Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING

Stephen E. Ambrose,

Nothing Like It In the World: The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad 1863-1869,

Simon & Schuster,

ISBN 978-0743203173

16

Week 16: Tuesday, February 11, 2025

The West After the War

Week 16

Bruce Thompson:

The language and the costume come from south of the border: corral, mustang, lasso, lariat, ranch, sombrero, chaps, bronco, wrangler (caballerango=horse herdsman), rodeo, buckaroo (from vaquero).

"There is a geographical band of demarcation through the middle of America where eastern mixed forest stops and tall-grass prairie begins to shade gently upward into short-grass plains, and where precipitation declines from more than twenty annual inches to as few as ten. It is not a precise boundary that can be drawn with a straightedge, but it can be traced generally downward from Canada through the eastern half of the Dakotas, central Nebraska, and western Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. And it extends, with some notable islands of exception (the Rockies, the Sierra, western Washington and Oregon), all the way to the Pacific slope. Its principal geophysical features, in order of importance, are aridity, treelessness, and a comparatively level surface."

—Page Stegner

The cowboy era is post-Civil War: the North American ranch began to emerge in the southern part of Texas during the 1860s. The peak came circa 1880; the crash in 1886-87. The cowboy worked on a ranch; his principal job was to round up cattle and drive them to market, i.e., to cattle towns like Abilene, from whence they would be shipped by rail to Chicago slaughterhouses.

The ranch was to the West what the plantation was to the South. From a sociological perspective, the system on the Western range "was one of wage laborers selling their services freely, sometimes for only a season or two, then moving on. With the job necessarily went a lot of autonomy. Since chasing after steers often took one far away from the scrutiny of a foreman, since in fact the work demanded a great deal of self-directedness and initiative, and since the hired men were allowed to ride big horses and carry big guns across a big space, there was relatively more personal freedom for workers in the ranching industry than in, say, the textile factory or the cotton field …

"Though it adopted terms, tools, and animal lore going back into the dim past of Iberian and Celtic antecedents, the ranch was unmistakably a modern capitalist institution. It took form in the marginal environments of the New World, where heretofore there had been only a few domesticated animals. It specialized in raising exotic cattle and other animals to sell in the marketplace, furnishing meat, hides, and wool to the growing metropolises of the East and to Europe. The animals were a mechanism for converting the western grasslands into a form suitable for human consumption. From the earliest period in the United States the scale of this industry was continental, growing up as it did with the national railroad lines: then, following the invention of the refrigerator ship in 1879, it became transoceanic and global." (Donald Worster).

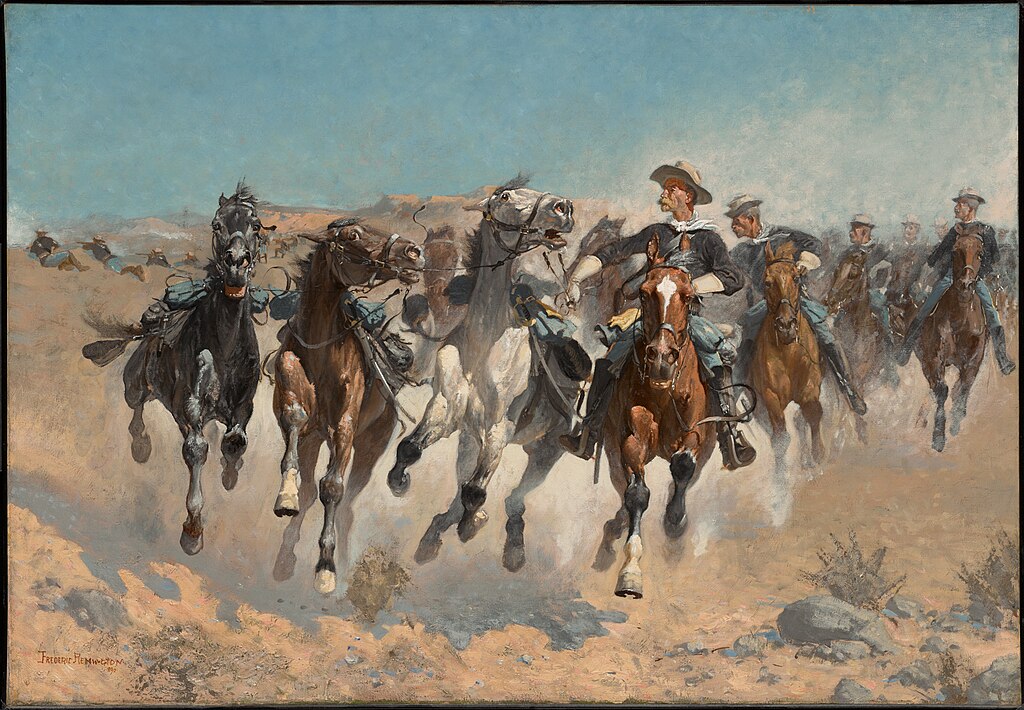

Below: Frederic Remington, Dismounted: The Fourth Troopers Moving the Led Horses, 1890, oil on canvas, Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts"

RECOMMENDED READING

Page Stegner,

Winning the Wild West: The Epic Saga of the American Frontier, 1800--1899,

Free Press,

ISBN 978-0743232913

17

Week 17: Tuesday, February 18, 2025

The Statue of Liberty

Week 17

The Statue of Liberty (Liberty Enlightening the World; French: La Liberté éclairant le monde) is a colossal neoclassical sculpture on Liberty Island in New York Harbor, within New York City. The copper statue, a gift to the U.S. from the people of France, was designed by French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi and its metal framework was built by Gustave Eiffel. The statue was dedicated on October 28, 1886.

The statue is a figure of Libertas, the Roman goddess of liberty. She holds a torch above her head with her right hand, and in her left hand carries a tabula ansata inscribed JULY IV MDCCLXXVI (July 4, 1776, in Roman numerals), the date of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. A broken chain and shackle lie at her feet as she walks forward, commemorating the national abolition of slavery following the American Civil War.[8] After its dedication the statue became an icon of freedom and of the United States, being subsequently seen as a symbol of welcome to immigrants arriving by sea.

By the late 1860s the United States was expanding, and its people multiplying, faster than any other country in history. At the beginning of the Civil War, the total population, North and South, free and slave, was 31,443,321. That placed it in the forefront of European countries, all of which (except France) were also expanding fast though entirely by natural increase. At the end of the Civil War decade, the US population was 39,818,449, an increase of more than a quarter. By 1880 it had passed the 50 million mark, by 1890 it was 62,847,714, more than any other European country except Russia and still growing at the rate of 25 percent a decade and more. By 1900 it was over 75 million, and the 100 million mark was passed during World War One.5 US birth-rates were consistently high by world standards, though declining relatively. White birth-rates, measured per 1,000 population per annum, fell from 55 in 1800 to 30.1 in 1900 (black rates, first measured in 1850 at 58.6, fell to 44.4 in 1900). But the infant mortality rate, measured in infant deaths per 1,000 live births, also fell: from 217.4 in 1850 to 120.1 in 1900 and under 100 in 1920 (black rates were about two-fifths higher). And life expectancy rose: from 38.9 years in 1850 to 49.6 in 1900, passing the 60 mark in the 1920s (black rates were about twelve years lower). These combined to produce a very high natural rate of population increase.6 This natural increase was accompanied by mass-immigration. From 1815 to the start of the Civil War, over 5 million people moved from Europe to the United States,

Johnson, Paul. A History of the American People (p. 513). HarperCollins.

18

Week 18: Tuesday, February 25, 2025

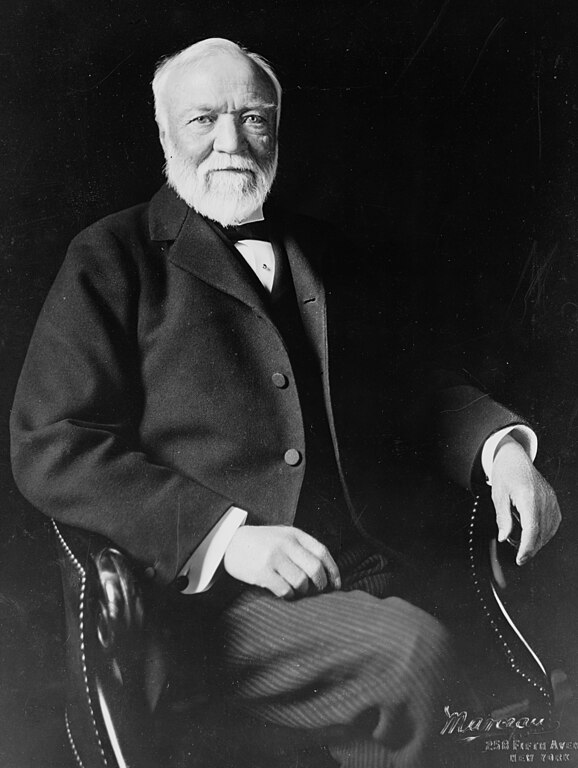

Andrew Carnegie

Week 18

Andrew Carnegie 1835 – 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans in history. He became a leading philanthropist in the United States, Great Britain, and the British Empire. During the last 18 years of his life, he gave away around $350 million (roughly $6.5 billion in 2023), almost 90 percent of his fortune, to charities, foundations and universities. His 1889 article proclaiming "The Gospel of Wealth" called on the rich to use their wealth to improve society, expressed support for progressive taxation and an estate tax, and stimulated a wave of philanthropy. Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland. He immigrated to what is now Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States with his parents in 1848 at the age of 12. Carnegie started work as a telegrapher. By the 1860s he had investments in railroads, railroad sleeping cars, bridges, and oil derricks. He accumulated further wealth as a bond salesman, raising money for American enterprise in Europe. He built Pittsburgh's Carnegie Steel Company, which he sold to J. P. Morgan in 1901 for $303,450,000 (equal to $11,113,550,000 today); it formed the basis of the U.S. Steel Corporation. After selling Carnegie Steel, he surpassed John D. Rockefeller as the richest American of the time. Carnegie devoted the remainder of his life to large-scale philanthropy, with special emphasis on building local libraries, working for world peace, education, and scientific research. He funded Carnegie Hall in New York City, the Peace Palace in The Hague, founded the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Carnegie Institution for Science, Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland, Carnegie Hero Fund, Carnegie Mellon University, and the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. (Wikipedia)

Andrew Carnegie 1835 – 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans in history. He became a leading philanthropist in the United States, Great Britain, and the British Empire. During the last 18 years of his life, he gave away around $350 million (roughly $6.5 billion in 2023), almost 90 percent of his fortune, to charities, foundations and universities. His 1889 article proclaiming "The Gospel of Wealth" called on the rich to use their wealth to improve society, expressed support for progressive taxation and an estate tax, and stimulated a wave of philanthropy. Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland. He immigrated to what is now Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States with his parents in 1848 at the age of 12. Carnegie started work as a telegrapher. By the 1860s he had investments in railroads, railroad sleeping cars, bridges, and oil derricks. He accumulated further wealth as a bond salesman, raising money for American enterprise in Europe. He built Pittsburgh's Carnegie Steel Company, which he sold to J. P. Morgan in 1901 for $303,450,000 (equal to $11,113,550,000 today); it formed the basis of the U.S. Steel Corporation. After selling Carnegie Steel, he surpassed John D. Rockefeller as the richest American of the time. Carnegie devoted the remainder of his life to large-scale philanthropy, with special emphasis on building local libraries, working for world peace, education, and scientific research. He funded Carnegie Hall in New York City, the Peace Palace in The Hague, founded the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Carnegie Institution for Science, Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland, Carnegie Hero Fund, Carnegie Mellon University, and the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. (Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING

19

Week 19: Tuesday, March 4, 2025

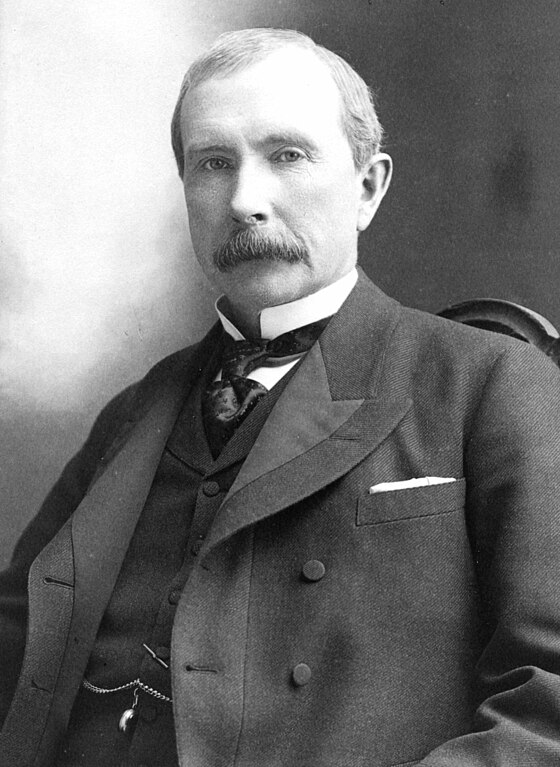

John D. Rockefeller

Week 19

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (1839 – 1937) was an American business magnate and philanthropist. He was one of the wealthiest Americans of all time and one of the richest people in modern history. Rockefeller was born into a large family in Upstate New Yorkwho moved several times before eventually settling in Cleveland, Ohio. He became an assistant bookkeeper at age 16 and went into several business partnerships beginning at age 20, concentrating his business on oil refining. Rockefeller founded the Standard Oil Company in 1870. He ran it until 1897 and remained its largest shareholder. In his retirement, he focused his energy and wealth on philanthropy, especially regarding education, medicine, higher education, and modernizing the Southern United States. Rockefeller's wealth soared as kerosene and gasoline grew in importance, and he became the richest person in the country, controlling 90% of all oil in the United States at his peak in 1900. Oil was used in lamps, and as a fuel for ships and automobiles. Standard Oil was the greatest business trust in the United States. Through use of the company's monopoly power, Rockefeller revolutionized the petroleum industry and, through corporate and technological innovations, was instrumental in both widely disseminating and drastically reducing the production cost of oil. Rockefeller's company and business practices came under criticism, particularly in the writings of author Ida Tarbell. The Supreme Court ruled in 1911 that Standard Oil must be dismantled for violation of federal antitrust laws. It was broken up into 34 separate entities, which included companies that became ExxonMobil, Chevron Corporation, and others—some of which remain among the largest companies by revenue worldwide. Consequently, Rockefeller became the country's first billionaire, with a fortune worth nearly 2% of the national economy. His personal wealth was estimated in 1913 at $900 million. Rockefeller spent much of the last 40 years of his life in retirement at Kykuit, his estate in Westchester County, New York, defining the structure of modern philanthropy, along with other key industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie. His fortune was used chiefly to create the modern systematic approach of targeted philanthropy through the creation of foundations that supported medicine, education, and scientific research. His foundations pioneered developments in medical research and were instrumental in the near-eradication of hookworm in the American South, and yellow fever in the United States. Rockefeller was the founder of the University of Chicago and Rockefeller University, and funded the establishment of Central Philippine University in the Philippines. He was a devout Northern Baptist and supported many church-based institutions. He adhered to total abstinence from alcohol and tobacco throughout his life. For advice, he relied closely on his wife, Laura Spelman Rockefeller: they had four daughters and a son together. He was a faithful congregant of the Erie Street Baptist Mission Church, taught Sunday school, and served as a trustee, clerk, and occasional janitor. Religion was a guiding force throughout his life, and he believed it to be the source of his success.

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (1839 – 1937) was an American business magnate and philanthropist. He was one of the wealthiest Americans of all time and one of the richest people in modern history. Rockefeller was born into a large family in Upstate New Yorkwho moved several times before eventually settling in Cleveland, Ohio. He became an assistant bookkeeper at age 16 and went into several business partnerships beginning at age 20, concentrating his business on oil refining. Rockefeller founded the Standard Oil Company in 1870. He ran it until 1897 and remained its largest shareholder. In his retirement, he focused his energy and wealth on philanthropy, especially regarding education, medicine, higher education, and modernizing the Southern United States. Rockefeller's wealth soared as kerosene and gasoline grew in importance, and he became the richest person in the country, controlling 90% of all oil in the United States at his peak in 1900. Oil was used in lamps, and as a fuel for ships and automobiles. Standard Oil was the greatest business trust in the United States. Through use of the company's monopoly power, Rockefeller revolutionized the petroleum industry and, through corporate and technological innovations, was instrumental in both widely disseminating and drastically reducing the production cost of oil. Rockefeller's company and business practices came under criticism, particularly in the writings of author Ida Tarbell. The Supreme Court ruled in 1911 that Standard Oil must be dismantled for violation of federal antitrust laws. It was broken up into 34 separate entities, which included companies that became ExxonMobil, Chevron Corporation, and others—some of which remain among the largest companies by revenue worldwide. Consequently, Rockefeller became the country's first billionaire, with a fortune worth nearly 2% of the national economy. His personal wealth was estimated in 1913 at $900 million. Rockefeller spent much of the last 40 years of his life in retirement at Kykuit, his estate in Westchester County, New York, defining the structure of modern philanthropy, along with other key industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie. His fortune was used chiefly to create the modern systematic approach of targeted philanthropy through the creation of foundations that supported medicine, education, and scientific research. His foundations pioneered developments in medical research and were instrumental in the near-eradication of hookworm in the American South, and yellow fever in the United States. Rockefeller was the founder of the University of Chicago and Rockefeller University, and funded the establishment of Central Philippine University in the Philippines. He was a devout Northern Baptist and supported many church-based institutions. He adhered to total abstinence from alcohol and tobacco throughout his life. For advice, he relied closely on his wife, Laura Spelman Rockefeller: they had four daughters and a son together. He was a faithful congregant of the Erie Street Baptist Mission Church, taught Sunday school, and served as a trustee, clerk, and occasional janitor. Religion was a guiding force throughout his life, and he believed it to be the source of his success.

(Wikipedia)

RECOMMENDED READING

20

Week 20: Tuesday, March 11, 2025

American Art 1850-1900

Week 20

The Hudson River School, led by Thomas Cole, who was born in Britain but emigrated to the United States when he was seventeen, was the first recognized American art movement. Centered in upper New York state, which was then wilderness, the artists associated with the movement emphasized the sublime and unique beauty of the American landscape. Influenced by Romanticism's concept of the sublime and Naturalism's emphasis on precise observed detail, Cole's landscapes like Kaaterskill Upper Fall, Catskill Mountains (1825) and Dunlap Lake with Dead Trees (Catskill) (1825) depicted American scenes to evoke the limitless possibilities of the new nation. Albert Bierstadt's Among the Sierra Nevada, California (1868) is one of many paintings that helped shape the image of 19th-century America as a promised land. Following Cole's death in 1848, Asher B. Durand, influenced by the French Barbizon School, led the turn toward a more naturalistic painting. The artists Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, John Frederick Kensett, George Inness, and Thomas Moran formed the second generation. Their works became enormously popular, as the exhibition of just one panoramic painting could draw thousands of visitors. In the 1860s, as Manifest Destiny with its call to go West became a dominant national force, Bierstadt and Moran turned their attention to panoramas of the dramatic western landscape, and, along with William Keith and Thomas Hill, were sometimes called the Rocky Mountain School. Their works also inspired and informed the movement to preserve America's natural wonders, including the Yellowstone and Grand Tetons Parks. Alternatively, the intimate scale and feeling of George Inness's works like The Delaware Valley (c.1863), and John Frederick Kensett's depictions of light reflecting on bodies of water played a pioneering role in developing what later came to be called Luminism. American painting changed in the post-Civil War world emphasizing colors and tones. You can see this in the early 1870s in James McNeill Whistler's series of Nocturnes that emphasized tonal harmonies, often in muted greens, blues, and dark colors, to depict landscapes at twilight. Of works like his famous and controversial Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (c.1875), Whistler said, "A nocturne is an arrangement of line, form and color first," but he also felt tonal harmonies were the visual equivalent of musical compositions. Born in America, Whistler lived most of his life in Britain where he played a pioneering role in a number of movements, including Japonism, the Aesthetic Movement, and the Anglo-Japanese aesthetic. George Inness and Albert Pinkham Ryder were also influenced by the French Barbizon School. Using gold and brown tones to depict a landscape at sunrise or sunset, Inness emphasized spiritual expression in works like "Sunrise" (1887), while Ryder often introduced a mythological narrative element into his mysterious landscapes that were precursors of Symbolism.

All

Week 1: Wed., Oct. 9, 2024

Our First Revolution

WEEK 1

We begin our study of the American Revolution with a look back into English history. The roots of the American Revolution are to be found in the great revolutionary upheaval of 1688 in England. In that year the English people rose up again against the king (James II) who was trying to impose upon them his own personal Roman Catholic religion. The English people had made it clear in their parliament again and again that they were an Anglican nation with the religion that was their own version of Protestantism, created during the reign of Henry VIII, and did not want to join the international Roman Catholic Church. King James II tried and tried and tried to drag the nation into his own Roman Catholic beliefs. This failed in 1688, when he was pushed out of office and sent into permanent exile in France. In the years immediately succeeding this event, the English people wrote a "Bill of Rights" which was imposed upon the new Protestant monarchs William and Mary. This event and the literature that accompanied the event (John Locke) provided the intellectual and legal basis for the American Revolution a century later. The title of our lecture is taken from a wonderful book by the American political scientist Michael Barone.(Our First Revolution)

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

From the Publisher:

"For too long we’ve lacked a compact, inexpensive, authoritative, and compulsively readable book that offers American readers a clear, informative, and inspiring narrative account of their country. Such a fresh retelling of the American story is especially needed today, to shape and deepen young Americans’ sense of the land they inhabit, help them to understand its roots and share in its memories, all the while equipping them for the privileges and responsibilities of citizenship in American society. The existing texts simply fail to tell that story with energy and conviction. Too often they reflect a fragmented outlook that fails to convey to American readers the grand trajectory of their own history. A great nation needs and deserves a great and coherent narrative, as an expression of its own self-understanding and its aspirations; and it needs to be able to convey that narrative effectively. Of course, it goes without saying that such a narrative cannot be a fairy tale of the past. It will not be convincing if it is not truthful. But as Land of Hope brilliantly shows, there is no contradiction between a truthful account of the American past and an inspiring one. Readers of Land of Hope will find both in its pages."

REVIEWS

“At a time of severe partisanship that has infected many accounts of our nation’s past, this brilliant new history, Land of Hope, written in lucid and often lyrical prose, is much needed. It is accurate, honest, and free of the unhistorical condescension so often paid to the people of America’s past. This generous but not uncritical story of our nation’s history ought to be read by every American. It explains and justifies the right kind of patriotism.”― Gordon S. Wood, author of Friends Divided: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson

“We’ve long needed a readable text that truly tells the American story, neither hiding the serious injustices in our history nor soft-pedaling our nation’s extraordinary achievements. Such a text cannot be a mere compilation of facts, and it certainly could not be written by someone lacking a deep understanding and appreciation of America’s constitutional ideals and institutions. Bringing his impressive skills as a political theorist, historian, and writer to bear, Wilfred McClay has supplied the need.”― Robert P. George, McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence, Princeton University

“No one has told the story of America with greater balance or better prose than Wilfred McClay. Land of Hope is a history book that you will not be able to put down. From the moment that ‘natives’ first crossed here over the Bering Strait, to the founding of America’s great experiment in republican government, to the horror and triumph of the Civil War...McClay’s account will capture your attention while offering an unforgettable education.”― James W. Ceaser, Professor of Politics, University of Virginia

Week 2: Wed., Oct. 16, 2024

18th Century Britain

WEEK 2

The revolutionary activities that unfolded in the colonies of North America during the 1760s and 1770s were all actions taken by Englishmen. The ideas, the books, the legal arguments, of all the major revolutionaries, Samuel Adams, John Adams, John Dickinson, Ben Franklin, all of these ideas were rooted in the events in England during the 1700s. The revolutionaries in Boston had no desire to break away from their English homeland. They thought like Englishman. They wrote books rooted in English legal traditions. They responded to the latest publications in London. And they were supported in England by voices in the English parliament. Therefore, as the revolutionary movement developed in Boston, Philadelphia and Virginia, the whole movement was filled with English ideas, books, and language. In our second week we will talk about this 18th century England with its Hanoverian kings and it's brilliant legal scholars.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

RECOMMENDED BOOK

Week 3: Wed., Oct. 23, 2024

18th Century France

WEEK 3

The revolutionaries in Boston in the 1760s and 1770s were first of all Englishmen. But they read French books. They knew the literature of the French Enlightenment well, Voltaire, Montesquieu, Rousseau, and others as well as the literature coming out of England. And as the crisis evolved, everyone in Boston and Philadelphia began to realize that if there was a break with England, the one most important nation that might help the colonies was the nation of France. The French Connection was complicated by the fact that France also was going through a pre-revolutionary phase. By the 1770s, Paris was on fire with revolutionary ideas and books that were widely read. But the overriding issue for the French government was any alliance that would help them fight their traditional enemies on the British island. Therefore, some alliance between the American colonies and the French nation was obvious to all. King Louis XVI was very much in favor of French help for the American colonies. If you would like to know something about the French Revolution here is a very useful short introduction.

RECOMMENDED READING

William Doyle,

The French Revolution: A Very Short Introduction,

Oxford University Press; 1 edition (December 6, 2001),

ISBN 0192853961

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

Week 4: Wed., Oct. 30, 2024

Empire

WEEK 4

"The Seven Years’ War was particularly important to the future of America, where it came to be referred to as the French and Indian War, and would last from 1754 to 1763. The French and Indian War was enormously consequential. It would dramatically change the map of North America. It would also force a rethinking of the entire relationship between England and her colonies and bring to an end any remaining semblance of the “salutary neglect” policy. And that change, in turn, would help pave the way to the American Revolution."

McClay, Wilfred M.. Land of Hope (p. 35). Encounter Books.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

Week 5: Wed., Nov. 6, 2024

The Boston Massacre

WEEK 5

The Boston Massacre was a confrontation in Boston on March 5, 1770, in which nine British soldiers shot several of a crowd of three or four hundred who were harassing them verbally and throwing various projectiles. The event was heavily publicized as "a massacre" by leading Patriots such as Paul Revere and Samuel Adams. British troops had been stationed in the Province of Massachusetts Bay since 1768 in order to support crown-appointed officials and to enforce unpopular Parliamentary legislation. Amid tense relations between the civilians and the soldiers, a mob formed around a British sentry and verbally abused him. He was eventually supported by seven additional soldiers, led by Captain Thomas Preston, who were hit by clubs, stones, and snowballs. Eventually, one soldier fired, prompting the others to fire without an order by Preston. The gunfire instantly killed three people and wounded eight others, two of whom later died of their wounds. Depictions, reports, and propaganda about the event heightened tensions throughout the Thirteen Colonies, notably the colored engraving produced by Paul Revere which you can see below.

David McCullough on John Adams and the British soldiers arrested and accused of murder:

"Samuel Adams was quick to call the killings a 'bloody butchery' and to distribute a print published by Paul Revere vividly portraying the scene as a slaughter of the innocent, an image of British tyranny, the Boston Massacre, that would become fixed in the public mind. The following day thirty-four-year-old John Adams was asked to defend the soldiers and their captain, when they came to trial. No one else would take the case, he was informed. . . .Adams accepted, firm in the belief, as he said, that no man in a free country should be denied the right to counsel and a fair trial, and convinced, on principle, that the case was of utmost importance. As a lawyer, his duty was clear. That he would be hazarding his hard-earned reputation and, in his words, 'incurring a clamor and popular suspicions and prejudices' against him, was obvious, and if some of what he later said on the subject would sound a little self-righteous, he was also being entirely honest. Only the year before, in 1769, Adams had defended four American sailors charged with killing a British naval officer who had boarded their ship with a press gang to grab them for the British navy. The sailors were acquitted on grounds of acting in self-defense, but public opinion had been vehement against the heinous practice of impressment. Adams had been in step with the popular outrage, exactly as he was out of step now. He worried for Abigail, who was pregnant again, and feared he was risking his family’s safety as well as his own, such was the state of emotions in Boston."

McCullough, David. John Adams . Simon & Schuster.

John Adams willingness to defend these British soldiers was one of the most courageous acts of his lifetime, and although at the time of the trial Bostonians ranted and raged against him, later when the trial was over and temperatures cooled down, it became clear to the larger public that Adams was an extraordinarily brave and wise man. The trial and the acquittal set Adams apart from other Bostonian leaders.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

Week 6: Wed., Nov. 13, 2024

Lexington and Concord

WEEK 6

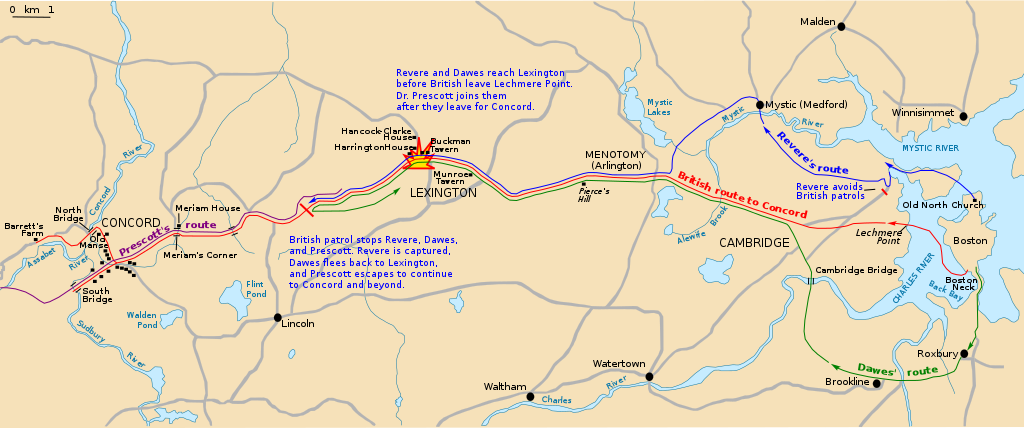

The Battles of Lexington and Concord, were the leading military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, Lincoln, Menotomy (present-day Arlington), and Cambridge. They marked the outbreak of armed conflict between the Kingdom of Great Britain and Patriot militias from America's thirteen colonies. In late 1774, Colonial leaders adopted the Suffolk Resolves in resistance to the alterations made to the Massachusetts colonial government by the British parliament following the Boston Tea Party. The colonial assembly responded by forming a Patriot provisional government known as the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and calling for local militias to train for possible hostilities. The Colonial government effectively controlled the colony outside of British-controlled Boston. In response, the British government in February 1775 declared Massachusetts to be in a state of rebellion. About 700 British Army regulars in Boston, under Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith, were given secret orders to capture and destroy Colonial military supplies reportedly stored by the Massachusetts militia at Concord. Through effective intelligence gathering, Patriot leaders had received word weeks before the expedition that their supplies might be at risk and had moved most of them to other locations. On the night before the battle, warning of the British expedition had been rapidly sent from Boston to militias in the area by several riders, including Paul Revere and Samuel Prescott, with information about British plans. The initial mode of the Army's arrival by water was signaled from the Old North Church in Boston to Charlestown using lanterns to communicate "one if by land, two if by sea". The first shots were fired just as the sun was rising at Lexington. Eight militiamen were killed, including Ensign Robert Munroe, their third in command. The British suffered only one casualty. The militia was outnumbered and fell back, and the regulars proceeded on to Concord, where they broke apart into companies to search for the supplies. At the North Bridge in Concord, approximately 400 militiamen engaged 100 regulars from three companies of the King's troops at about 11:00 am, resulting in casualties on both sides. The outnumbered regulars fell back from the bridge and rejoined the main body of British forces in Concord. The British forces began their return march to Boston after completing their search for military supplies, and more militiamen continued to arrive from the neighboring towns. Gunfire erupted again between the two sides and continued throughout the day as the regulars marched back towards Boston. Upon returning to Lexington, Lt. Col. Smith's expedition was rescued by reinforcements under Brigadier General Hugh Percy, a future Duke of Northumberland styled at this time by the courtesy title Earl Percy. The combined force of about 1,700 men marched back to Boston under heavy fire in a tactical withdrawal and eventually reached the safety of Charlestown. The accumulated militias then blockaded the narrow land accesses to Charlestown and Boston, starting the siege of Boston. Ralph Waldo Emerson describes the first shot fired by the Patriots at the North Bridge in his "Concord Hymn" as the "shot heard round the world". (Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

RECOMMENDED READING

From the Publisher:America’s beloved and distinguished historian presents, in a book of breathtaking excitement, drama, and narrative force, the stirring story of the year of our nation’s birth, 1776, interweaving, on both sides of the Atlantic, the actions and decisions that led Great Britain to undertake a war against her rebellious colonial subjects and that placed America’s survival in the hands of George Washington. In this masterful book, David McCullough tells the intensely human story of those who marched with General George Washington in the year of the Declaration of Independence—when the whole American cause was riding on their success, without which all hope for independence would have been dashed and the noble ideals of the Declaration would have amounted to little more than words on paper. Based on extensive research in both American and British archives, 1776 is a powerful drama written with extraordinary narrative vitality. It is the story of Americans in the ranks, men of every shape, size, and color, farmers, schoolteachers, shoemakers, no-accounts, and mere boys turned soldiers. And it is the story of the King’s men, the British commander, William Howe, and his highly disciplined redcoats who looked on their rebel foes with contempt and fought with a valor too little known.

Week 7: Wed., Nov. 20, 2024

Philadelphia 1775-1776

WEEK 7

The Second Continental Congress was the 1775-76 meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolution and its associated Revolutionary War that established American independence from the British Empire. The Congress created a new country that it first named the United Colonies, and in 1776, renamed the United States of America. The Congress began convening in Philadelphia, on May 10, 1775, with representatives from 12 of the 13 colonies, after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. The Second Continental Congress succeeded the First Continental Congress, which also met in Philadelphia from September 5 to October 26, 1774. The Second Congress functioned as the de facto national government at the outset of the Revolutionary War by raising militias, directing strategy, appointing diplomats, and writing petitions such as the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms and the Olive Branch Petition. All 13 colonies were represented by the time the Congress adopted the Lee Resolution, which declared independence from Britain on July 2, 1776, and the Congress unanimously agreed to the Declaration of Independence two days later. Congress functioned as the provisional government of the United States of America through March 1, 1781. During this period, it successfully managed the war effort, drafted the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, adopted the first U.S. constitution, secured diplomatic recognition and support from foreign nations, and resolved state land claims west of the Appalachian Mountains. Many of the delegates who attended the Second Congress had also attended the First. They again elected Peyton Randolph as president of the Congress and Charles Thomson as secretary. Notable new arrivals included Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania and John Hancock of Massachusetts. Within two weeks, Randolph was summoned back to Virginia to preside over the House of Burgesses; Hancock succeeded him as president, and Thomas Jefferson replaced him in the Virginia delegation. The number of participating colonies also grew, as Georgia endorsed the Congress in July 1775 and adopted the continental ban on trade with Britain. (Wikipedia)(/p>

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

RECOMMENDED READING

From the Publisher:America’s beloved and distinguished historian presents, in a book of breathtaking excitement, drama, and narrative force, the stirring story of the year of our nation’s birth, 1776, interweaving, on both sides of the Atlantic, the actions and decisions that led Great Britain to undertake a war against her rebellious colonial subjects and that placed America’s survival in the hands of George Washington. In this masterful book, David McCullough tells the intensely human story of those who marched with General George Washington in the year of the Declaration of Independence—when the whole American cause was riding on their success, without which all hope for independence would have been dashed and the noble ideals of the Declaration would have amounted to little more than words on paper. Based on extensive research in both American and British archives, 1776 is a powerful drama written with extraordinary narrative vitality. It is the story of Americans in the ranks, men of every shape, size, and color, farmers, schoolteachers, shoemakers, no-accounts, and mere boys turned soldiers. And it is the story of the King’s men, the British commander, William Howe, and his highly disciplined redcoats who looked on their rebel foes with contempt and fought with a valor too little known.

RECOMMENDED READING

Pauline Maier,

American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence,

Vintage,

ISBN 978-0679779087

NEXT WEEK IS THANKSGIVING WEEK

NO CLASSES ALL WEEK OF NOV 25-29 2024

Week 8: Wed., Dec. 4, 2024

Ben Franklin in Paris

WEEK 8

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

RECOMMENDED READING

Walter Isaacson,

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life,

Simon & Schuster (June 1, 2004),

ISBN 978-0743258074

Week 9: Wed., Dec. 11, 2024

Washington at War

WEEK 9

George Washington: ""I have often thought how much happier I should have been if, instead of accepting a command under such circumstances, I should have taken my musket upon my Shoulder & entered the Ranks or … had retir'd to the back country & lived in a Wig-wam."

—George Washington to Joseph Reed, 14 January 1776

WASHINGTON'S WAR BEGINS IN BOSTON SUMMER 1775

The siege of Boston (April 19, 1775 – March 17, 1776) was the opening phase of the American Revolutionary War. New England militiamen prevented the British Army from moving by land, and it was garrisoned in Boston, Massachusetts Bay. Both sides had to deal with resource, supply, and personnel issues over the course of the siege. British resupply and reinforcement was limited to sea access, which was impeded by American vessels. The British abandoned Boston after 11 months and transferred their troops and equipment to Nova Scotia. The siege began on April 19 after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, when Massachusetts militias blocked land access to Boston. The Continental Congress formed the Continental Army from the militias involved in the fighting and appointed George Washington as Commander in Chief. In June 1775, the British seized Bunker Hill, from which the Continentals were preparing to bombard the city, but their casualties were heavy and their gains insufficient to break the Continental Army's control over land access to Boston. After this, the Americans laid siege to the city; no major battles were fought during this time, and the conflict was limited to occasional raids, minor skirmishes, and sniper fire. British efforts to supply their troops were significantly impeded by the smaller but more agile American forces operating on land and sea, and the British consequently suffered from a continual lack of food, fuel, and supplies. In November 1775, George Washington sent Henry Knox on a mission to bring the heavy artillery that had recently been captured at Fort Ticonderoga. In a technically complex and demanding operation, Knox brought the cannons to Boston in January 1776, and this artillery fortified Dorchester Heights which overlooked Boston harbor. This development threatened to cut off the British supply lifeline from the sea. British commander William Howe saw his position as indefensible, and he withdrew his forces from Boston to Halifax, Nova Scotia on March 17.

WASHINGTON IN NEW YORK

David McCullough, 1776: "At Boston, Washington had known exactly where the enemy was, and who they were, and what was needed to contain them. At Boston the British had been largely at his mercy, and especially once winter set it. Here, with their overwhelming naval might and absolute control of the waters, they could strike at will and from almost any direction. The time and place of the battle would be entirely their choice, and this was the worry overriding all others….At Boston, Washington had benefited from a steady supply of valuable intelligence coming out of the besieged town, while Howe had known little or nothing of Washington's strengths or intentions. Here, with so much of the population still loyal to the king, the situation was the reverse." Washington: "The designs of the Enemy are too much behind the Curtain for me to form any accurate opinion of their Plan of operations… we are left to wander in the field of conjecture."

The British at New York: Joseph Ellis: "In a nearly miraculous burst of logistical energy, Great Britain assembled a fleet of 427 ships equipped with 1,200 cannons to transport 32,000 soldiers and 10,000 sailors across the Atlantic. It was the largest amphibious operation ever attempted by any European power, with an attack force larger than the population of Philadelphia, the biggest city in America" Last to arrive at New York, "was Admiral Richard Howe with by far the largest fleet, more than 150 ships with 20,000 troops and a six-month supply of food and munitions, by itself the largest armada to cross the Atlantic before the American Expeditionary Force in WWI."

This sketch by a British officer on Staten Island shows part of the king’s fleet anchored in the Narrows, across from Long Island on July 12, 1776. Admiral Howe’s flagship, Eagle, can be seen in the middle distance, approaching from the open sea.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

RECOMMENDED READING

From the Publisher:In Washington: A Life celebrated biographer Ron Chernow provides a richly nuanced portrait of the father of our nation. With a breadth and depth matched by no other one-volume life of Washington, this crisply paced narrative carries the reader through his troubled boyhood, his precocious feats in the French and Indian War, his creation of Mount Vernon, his heroic exploits with the Continental Army, his presiding over the Constitutional Convention, and his magnificent performance as America's first president. Despite the reverence his name inspires, Washington remains a lifeless waxwork for many Americans, worthy but dull. A laconic man of granite self-control, he often arouses more respect than affection. In this groundbreaking work, based on massive research, Chernow dashes forever the stereotype of a stolid, unemotional man. A strapping six feet, Washington was a celebrated horseman, elegant dancer, and tireless hunter, with a fiercely guarded emotional life. Chernow brings to vivid life a dashing, passionate man of fiery opinions and many moods. Probing his private life, he explores his fraught relationship with his crusty mother, his youthful infatuation with the married Sally Fairfax, and his often conflicted feelings toward his adopted children and grandchildren. He also provides a lavishly detailed portrait of his marriage to Martha and his complex behavior as a slave master. At the same time, Washington is an astute and surprising portrait of a canny political genius who knew how to inspire people. Not only did Washington gather around himself the foremost figures of the age, including James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson, but he also brilliantly orchestrated their actions to shape the new federal government, define the separation of powers, and establish the office of the presidency. In this unique biography, Ron Chernow takes us on a page-turning journey through all the formative events of America's founding. With a dramatic sweep worthy of its giant subject, Washington is a magisterial work from one of our most elegant storytellers.

RECOMMENDED READING

David Hackett Fischer,

Washington's Crossing (Pivotal Moments in American History),

Oxford University Press; Reprint edition (February 1, 2006),

ISBN 978-0195181593

Week 10: Wed., Dec. 18, 2024

Peace of Paris 1783

WEEK 10

1773 Dec. 16, Boston Tea Party

1774 Jan, Boston under British lockdown

1775 April 19, Battle of Lexington & Concord

1775 June 17 Battle of Bunker Hill

1775 July George Washington takes command in Boston

1775 Nov. Henry Knox goes to Ticonderoga for guns

1776 Jan. Knox and guns arrive at Boston

1776 Jan. Thomas Paine publishes "Common Sense"

1776 Mar. Washington puts guns on Dorchester Heights

1776 March 17 British evacuate Boston

1776 July British arrive in New York

1776 July 4, Declaration of Independence

1776 Aug. 27 Battle of Brooklyn Washington defeated

1776 Nov. 16 Washington loses New York

1776 Dec. 25/26 Washington wins Battle of Trenton

1777 Jan. 3, Washington wins Battle of Princeton

1777 Sept 19-Oct 7, Americans win Battle of Saratoga; brings in French aid

1778 Feb. 6, French-American alliance announced

1778 June 28, Battle of Monmouth, Geo Washington saves the day

1779 Feb. 3, Battle of Port Royal Island SC

1779 Nov Washington’s Main Army begins camping at Morristown, NJ

1780 Oct 7, Americans win Battle of Kings Mountain;

Thomas Jefferson called the battle "The turn of the tide of success."

1781 Mar 2, Articles of Confederation adopted

1781 Sep 28-Oct 19 - Siege of Yorktown, VA

1781 Oct 19, General Cornwallis officially surrenders at Yorktown, VA

1783 Sept 3, US and British sign Treaty of Paris

RECOMMENDED READING

The Chernow biography is the best source for the later war and its conclusion.