- Week 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- All

Week 21

Week 21: Tuesday, April 1, 2025

The Homestead Strike

Week 21

The Homestead strike, was an industrial lockout and strike that began on July 1, 1892, culminating in a battle in which strikers defeated private security agents on July 6, 1892. The governor responded by sending in the National Guard to protect strikebreakers. The dispute occurred at the Homestead Steel Works in the Pittsburgh-area town of Homestead, Pennsylvania, between the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers (the AA) and the Carnegie Steel Company. The final result was a major defeat for the union strikers and a setback for their efforts to unionize steelworkers. The battle was a pivotal event in U.S. labor history. Carnegie Steel made major technological innovations in the 1880s, especially the installation of the open-hearth system at Homestead in 1886. It now became possible to make steel suitable for structural beams and for armor plate for the United States Navy, which paid far higher prices for the premium product. In addition, the plant moved increasingly toward the continuous system of production. Carnegie installed vastly improved systems of material-handling, like overhead cranes, hoists, charging machines, and buggies. All of this greatly sped up the process of steelmaking, and allowed the production of vastly larger quantities of the product. As the mills expanded, the labor force grew rapidly, especially with unskilled workers. However, while Carnegie Steel grew and progressed, workers at Homestead were seeing their wages drop. (Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

From the Publisher:

"For too long we’ve lacked a compact, inexpensive, authoritative, and compulsively readable book that offers American readers a clear, informative, and inspiring narrative account of their country. Such a fresh retelling of the American story is especially needed today, to shape and deepen young Americans’ sense of the land they inhabit, help them to understand its roots and share in its memories, all the while equipping them for the privileges and responsibilities of citizenship in American society. The existing texts simply fail to tell that story with energy and conviction. Too often they reflect a fragmented outlook that fails to convey to American readers the grand trajectory of their own history. A great nation needs and deserves a great and coherent narrative, as an expression of its own self-understanding and its aspirations; and it needs to be able to convey that narrative effectively. Of course, it goes without saying that such a narrative cannot be a fairy tale of the past. It will not be convincing if it is not truthful. But as Land of Hope brilliantly shows, there is no contradiction between a truthful account of the American past and an inspiring one. Readers of Land of Hope will find both in its pages."

REVIEWS

“At a time of severe partisanship that has infected many accounts of our nation’s past, this brilliant new history, Land of Hope, written in lucid and often lyrical prose, is much needed. It is accurate, honest, and free of the unhistorical condescension so often paid to the people of America’s past. This generous but not uncritical story of our nation’s history ought to be read by every American. It explains and justifies the right kind of patriotism.”― Gordon S. Wood, author of Friends Divided: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson

“We’ve long needed a readable text that truly tells the American story, neither hiding the serious injustices in our history nor soft-pedaling our nation’s extraordinary achievements. Such a text cannot be a mere compilation of facts, and it certainly could not be written by someone lacking a deep understanding and appreciation of America’s constitutional ideals and institutions. Bringing his impressive skills as a political theorist, historian, and writer to bear, Wilfred McClay has supplied the need.”― Robert P. George, McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence, Princeton University

“No one has told the story of America with greater balance or better prose than Wilfred McClay. Land of Hope is a history book that you will not be able to put down. From the moment that ‘natives’ first crossed here over the Bering Strait, to the founding of America’s great experiment in republican government, to the horror and triumph of the Civil War...McClay’s account will capture your attention while offering an unforgettable education.”― James W. Ceaser, Professor of Politics, University of Virginia

22

Week 22: Tuesday, April 8, 2025

The Sherman Anti-Trust Act

Week 22

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (26 Stat. 209, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1–7) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce and consequently prohibits unfair monopolies. It was passed by Congress and is named for Senator John Sherman, its principal author. The Sherman Act broadly prohibits 1) anticompetitive agreements and 2) unilateral conduct that monopolizes or attempts to monopolize the relevant market. The Act authorizes the Department of Justice to bring suits to enjoin (i.e. prohibit) conduct violating the Act, and additionally authorizes private parties injured by conduct violating the Act to bring suits for treble damages (i.e. three times as much money in damages as the violation cost them). Over time, the federal courts have developed a body of law under the Sherman Act making certain types of anticompetitive conduct per se illegal, and subjecting other types of conduct to case-by-case analysis regarding whether the conduct unreasonably restrains trade. The law attempts to prevent the artificial raising of prices by restriction of trade or supply. "Innocent monopoly", or monopoly achieved solely by merit, is legal, but acts by a monopolist to artificially preserve that status, or nefarious dealings to create a monopoly, are not. The purpose of the Sherman Act is not to protect competitors from harm from legitimately successful businesses, nor to prevent businesses from gaining honest profits from consumers, but rather to preserve a competitive marketplace to protect consumers from abuses. Senator John Sherman is pictured above.

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (26 Stat. 209, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1–7) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce and consequently prohibits unfair monopolies. It was passed by Congress and is named for Senator John Sherman, its principal author. The Sherman Act broadly prohibits 1) anticompetitive agreements and 2) unilateral conduct that monopolizes or attempts to monopolize the relevant market. The Act authorizes the Department of Justice to bring suits to enjoin (i.e. prohibit) conduct violating the Act, and additionally authorizes private parties injured by conduct violating the Act to bring suits for treble damages (i.e. three times as much money in damages as the violation cost them). Over time, the federal courts have developed a body of law under the Sherman Act making certain types of anticompetitive conduct per se illegal, and subjecting other types of conduct to case-by-case analysis regarding whether the conduct unreasonably restrains trade. The law attempts to prevent the artificial raising of prices by restriction of trade or supply. "Innocent monopoly", or monopoly achieved solely by merit, is legal, but acts by a monopolist to artificially preserve that status, or nefarious dealings to create a monopoly, are not. The purpose of the Sherman Act is not to protect competitors from harm from legitimately successful businesses, nor to prevent businesses from gaining honest profits from consumers, but rather to preserve a competitive marketplace to protect consumers from abuses. Senator John Sherman is pictured above.

REQUIRED READING

See Chapter 12: "A Nation Transformed"

23

Week 23: Tuesday, April 15, 2025

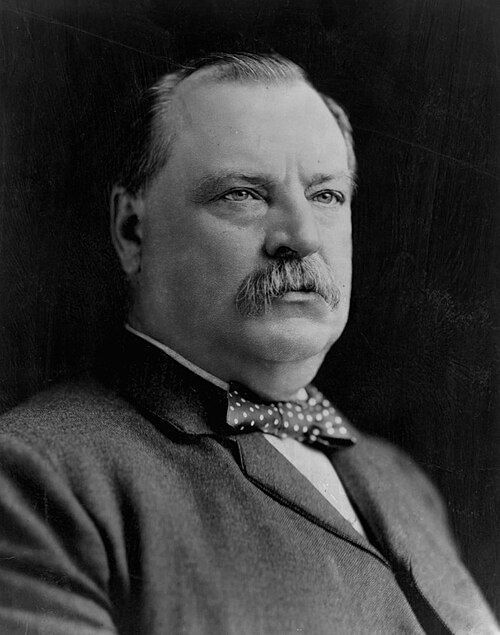

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837 – June 24, 1908) served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, from 1885 to 1889 and again from 1893 to 1897. He was the first Democrat to win election to the presidency after the Civil War and the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms. Born in Caldwell, New Jersey, Cleveland was elected mayor of Buffalo in 1881 and governor of New York in 1882. While governor, he closely cooperated with state assembly minority leader Theodore Roosevelt to pass reform measures, winning national attention. He led the Bourbon Democrats, a pro-business movement opposed to high tariffs, free silver, inflation, imperialism, and subsidies to businesses, farmers, or veterans. His crusade for political reform and fiscal conservatism made him an icon for American conservatives of the time. Cleveland also won praise for honesty, self-reliance, integrity, and commitment to the principles of classical liberalism. His fight against political corruption, patronage, and bossism convinced many like-minded Republicans, called "Mugwumps", to cross party lines and support him in the 1884 presidential election, which he narrowly won against Republican James G. Blaine. (Wikipedia)

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837 – June 24, 1908) served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, from 1885 to 1889 and again from 1893 to 1897. He was the first Democrat to win election to the presidency after the Civil War and the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms. Born in Caldwell, New Jersey, Cleveland was elected mayor of Buffalo in 1881 and governor of New York in 1882. While governor, he closely cooperated with state assembly minority leader Theodore Roosevelt to pass reform measures, winning national attention. He led the Bourbon Democrats, a pro-business movement opposed to high tariffs, free silver, inflation, imperialism, and subsidies to businesses, farmers, or veterans. His crusade for political reform and fiscal conservatism made him an icon for American conservatives of the time. Cleveland also won praise for honesty, self-reliance, integrity, and commitment to the principles of classical liberalism. His fight against political corruption, patronage, and bossism convinced many like-minded Republicans, called "Mugwumps", to cross party lines and support him in the 1884 presidential election, which he narrowly won against Republican James G. Blaine. (Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING

See Chapter 12: "A Nation Transformed"

24

Week 24: Tuesday, April 22, 2025

The Panic of 1893

Week 24

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States. It began in February 1893 and officially ended eight months later, but the effects from it continued to be felt until 1897. It was the most serious economic depression in history until the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Panic of 1893 deeply affected every sector of the economy and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment and the presidency of William McKinley. The Panic of 1893 has been traced to many causes, one of them pointing to Argentina; investment was encouraged by the Argentine agent bank, Baring Brothers. However, the 1890 wheat crop failure and a failed coup in Buenos Aires ended further investments. In addition, speculations in South African and Australian properties also collapsed. Because European investors were concerned that these problems might spread, they started a run on gold in the U.S. Treasury. Specie was considered more valuable than paper money; when people were uncertain about the future, they hoarded specie and rejected paper notes. During the Gilded Age of the 1870s and 1880s, the United States had experienced economic growth and expansion, but much of this expansion depended on high international commodity prices. Exacerbating the problems with international investments, wheat prices crashed in 1893. In particular, the opening of numerous mines in the western United States led to an oversupply of silver, leading to significant debate as to how much of the silver should be coined into money. During the 1880s, American railroads experienced what might today be called a "bubble": investors flocked to railroads, and they were greatly over-built. One of the first clear signs of trouble came on 20 February 1893, twelve days before the inauguration of U.S. President Grover Cleveland, with the appointment of receivers for the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, which had greatly overextended itself. Upon taking office, Cleveland dealt directly with the Treasury crisis and convinced Congress to repeal the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which he felt was mainly responsible for the economic crisis. As concern for the state of the economy deepened, people rushed to withdraw their money from banks, and caused bank runs. The credit crunch rippled through the economy. A financial panic in London combined with a drop in continental European trade caused foreign investors to sell American stocks to obtain American funds backed by gold. (Wikipedia)

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States. It began in February 1893 and officially ended eight months later, but the effects from it continued to be felt until 1897. It was the most serious economic depression in history until the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Panic of 1893 deeply affected every sector of the economy and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment and the presidency of William McKinley. The Panic of 1893 has been traced to many causes, one of them pointing to Argentina; investment was encouraged by the Argentine agent bank, Baring Brothers. However, the 1890 wheat crop failure and a failed coup in Buenos Aires ended further investments. In addition, speculations in South African and Australian properties also collapsed. Because European investors were concerned that these problems might spread, they started a run on gold in the U.S. Treasury. Specie was considered more valuable than paper money; when people were uncertain about the future, they hoarded specie and rejected paper notes. During the Gilded Age of the 1870s and 1880s, the United States had experienced economic growth and expansion, but much of this expansion depended on high international commodity prices. Exacerbating the problems with international investments, wheat prices crashed in 1893. In particular, the opening of numerous mines in the western United States led to an oversupply of silver, leading to significant debate as to how much of the silver should be coined into money. During the 1880s, American railroads experienced what might today be called a "bubble": investors flocked to railroads, and they were greatly over-built. One of the first clear signs of trouble came on 20 February 1893, twelve days before the inauguration of U.S. President Grover Cleveland, with the appointment of receivers for the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, which had greatly overextended itself. Upon taking office, Cleveland dealt directly with the Treasury crisis and convinced Congress to repeal the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which he felt was mainly responsible for the economic crisis. As concern for the state of the economy deepened, people rushed to withdraw their money from banks, and caused bank runs. The credit crunch rippled through the economy. A financial panic in London combined with a drop in continental European trade caused foreign investors to sell American stocks to obtain American funds backed by gold. (Wikipedia)

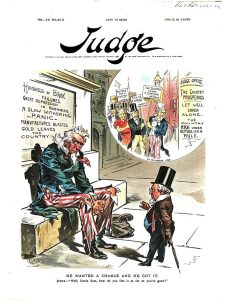

The pro-Republican party cartoon above suggests that the Panic was the fault of the newly elected Democrats.

Caption:He wanted a change and he got it.

Judge standing in front of Uncle Sam asks him, "Well, Uncle Sam, how do you like it as far as you've gone?"

REQUIRED READING

See Chapter 12: "A Nation Transformed"

25

Week 25: Tuesday, April 29, 2025

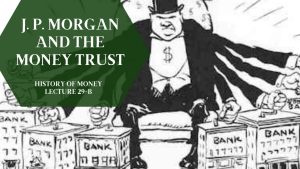

J. P. Morgan

Week 25

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. As the head of the banking firm that ultimately became known as J.P. Morgan & Co., he was a driving force behind the wave of industrial consolidations in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century. Over the course of his career on Wall Street, Morgan spearheaded the formation of several prominent multinational corporations including U.S. Steel, International Harvester, and General Electric. He and his partners also held controlling interests in numerous other American businesses including Aetna, Western Union, the Pullman Car Company, and 21 railroads. His grandfather Joseph Morgan was one of the co-founders of Aetna. Through his holdings, Morgan exercised enormous influence over capital markets in the United States. During the Panic of 1907, he organized a coalition of financiers that saved the American monetary system from collapse. As the Progressive Era's leading financier, Morgan's dedication to efficiency and modernization helped transform the shape of the American economy. Adrian Wooldridge characterized Morgan as America's "greatest banker." Morgan died in Rome, Italy, in his sleep in 1913 at the age of 75, leaving his fortune and business to his son, J. P. Morgan Jr. Biographer Ron Chernow estimated his fortune at $80 million (equivalent to $1.8 billion in 2023).

26

Week 26: Tuesday, May 6, 2025

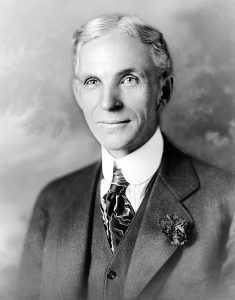

Henry Ford

Week 26

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist and business magnate. As the founder of the Ford Motor Company, he is credited as a pioneer in making vehicles affordable for middle-class Americans through the system that came to be known as Fordism. In 1911, he was awarded a patent for the transmission mechanism that would be used in the Ford Model T and other vehicles.Ford was born in a farmhouse in Springwells Township, Michigan, and left home at the age of 16 to find work in Detroit. It was a few years before this time that Ford first experienced automobiles, and throughout the later half of the 1880s, he began repairing and later constructing engines, and through the 1890s worked with a division of Edison Electric. He founded the Ford Motor Company in 1903 after prior failures in business, but success in constructing vehicles. The introduction of the Ford Model T vehicle in 1908 is credited with having revolutionized both transportation and American industry. As the sole owner of the Ford Motor Company, Ford became one of the wealthiest people in the world. He was also among the pioneers of the five-day work-week. Ford believed that consumerism could help to bring about world peace. His commitment to systematically lowering costs resulted in many technical and business innovations, including a franchise system, which allowed for car dealerships throughout North America and in major cities on six continents. Ford was known for his pacifism during the first years of World War I, although during the war his company became a major supplier of weapons. He promoted the League of Nations. In the 1920s Ford promoted antisemitism through his newspaper The Dearborn Independent and the book The International Jew. He opposed his country's entry into World War II, and served for a time on the board of the America First Committee. After his son Edsel died in 1943, Ford resumed control of the company, but was too frail to make decisions and quickly came under the control of several of his subordinates. He turned over the company to his grandson Henry Ford II in 1945. Upon his death in 1947, he left most of his wealth to the Ford Foundation, and control of the company to his family.

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist and business magnate. As the founder of the Ford Motor Company, he is credited as a pioneer in making vehicles affordable for middle-class Americans through the system that came to be known as Fordism. In 1911, he was awarded a patent for the transmission mechanism that would be used in the Ford Model T and other vehicles.Ford was born in a farmhouse in Springwells Township, Michigan, and left home at the age of 16 to find work in Detroit. It was a few years before this time that Ford first experienced automobiles, and throughout the later half of the 1880s, he began repairing and later constructing engines, and through the 1890s worked with a division of Edison Electric. He founded the Ford Motor Company in 1903 after prior failures in business, but success in constructing vehicles. The introduction of the Ford Model T vehicle in 1908 is credited with having revolutionized both transportation and American industry. As the sole owner of the Ford Motor Company, Ford became one of the wealthiest people in the world. He was also among the pioneers of the five-day work-week. Ford believed that consumerism could help to bring about world peace. His commitment to systematically lowering costs resulted in many technical and business innovations, including a franchise system, which allowed for car dealerships throughout North America and in major cities on six continents. Ford was known for his pacifism during the first years of World War I, although during the war his company became a major supplier of weapons. He promoted the League of Nations. In the 1920s Ford promoted antisemitism through his newspaper The Dearborn Independent and the book The International Jew. He opposed his country's entry into World War II, and served for a time on the board of the America First Committee. After his son Edsel died in 1943, Ford resumed control of the company, but was too frail to make decisions and quickly came under the control of several of his subordinates. He turned over the company to his grandson Henry Ford II in 1945. Upon his death in 1947, he left most of his wealth to the Ford Foundation, and control of the company to his family.

REQUIRED READING

See pp 281-283.

27

Week 27: Tuesday, May 13, 2025

Stanford White and American Architecture

Week 27

Stanford White (November 9, 1853 – June 25, 1906) was an American architect and a partner in the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, one of the most significant Beaux-Arts firms at the turn of the 20th century. White designed many houses for the wealthy, in addition to numerous civic, institutional and religious buildings. His temporary Washington Square Arch was so popular that he was commissioned to design a permanent one. White's design principles embodied the "American Renaissance". In 1906, White was murdered during a musical performance at the rooftop theatre of Madison Square Garden. His killer, Harry Kendall Thaw, was a wealthy but mentally unstable heir of a coal and railroad fortune who had become obsessed by White's alleged drugging and rape of, and subsequent relationship with, the woman who was to become Thaw's wife, Evelyn Nesbit, which had started when she was aged 16. At the time of White's killing, Nesbit was a famous fashion model. With the public nature of the killing and elements of a sex scandal among the wealthy, the resulting trial of Thaw was dubbed the "Trial of the Century" by contemporary reporters. Thaw was ultimately found not guilty by reason of insanity.

Stanford White (November 9, 1853 – June 25, 1906) was an American architect and a partner in the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, one of the most significant Beaux-Arts firms at the turn of the 20th century. White designed many houses for the wealthy, in addition to numerous civic, institutional and religious buildings. His temporary Washington Square Arch was so popular that he was commissioned to design a permanent one. White's design principles embodied the "American Renaissance". In 1906, White was murdered during a musical performance at the rooftop theatre of Madison Square Garden. His killer, Harry Kendall Thaw, was a wealthy but mentally unstable heir of a coal and railroad fortune who had become obsessed by White's alleged drugging and rape of, and subsequent relationship with, the woman who was to become Thaw's wife, Evelyn Nesbit, which had started when she was aged 16. At the time of White's killing, Nesbit was a famous fashion model. With the public nature of the killing and elements of a sex scandal among the wealthy, the resulting trial of Thaw was dubbed the "Trial of the Century" by contemporary reporters. Thaw was ultimately found not guilty by reason of insanity.

Rosecliff as seen from the front. Built by Theresa Fair Oelrichs heiress to the Comstock Lode fortune. Rosecliff is located in Newport, Rhode Island and was built between 1898 and 1902.

28

Week 28: Tuesday, May 20, 2025

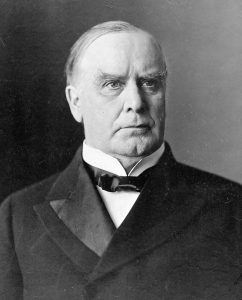

William McKinley

Week 28

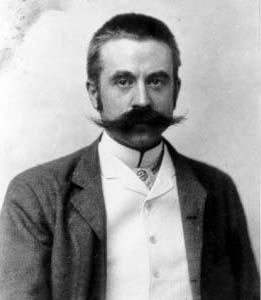

William McKinley (January 29, 1843 – September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party, he led a realignment that made Republicans largely dominant in the industrial states and nationwide for decades. He successfully led the U.S. in the Spanish–American War, overseeing a period of American expansionism, with the annexations of Puerto Rico, Guam, the Philippines, and Hawaii. McKinley also rejected inflationary plans such as free silver in favor of keeping the nation on the gold standard, and raised protective tariffs. McKinley was the last president to have served in the American Civil War; he was the only one to begin his service as an enlisted man and ended it as a brevet major. After the war, he settled in Canton, Ohio, where he practiced law and married Ida Saxton. In 1876, McKinley was elected to Congress, where he became the Republican expert on the protective tariff, which he believed would bring prosperity. His 1890 McKinley Tariff was highly controversial and, together with a Democratic redistricting aimed at gerrymandering him out of office, led to his defeat in the Democratic landslide of 1890. He was elected governor of Ohio in 1891 and 1893, steering a moderate course between capital and labor interests. He secured the Republican nomination for president in 1896 amid a deep economic depression and defeated his Democratic rival William Jennings Bryan after a front porch campaign in which he advocated "sound money" (the gold standard unless altered by international agreement) and promised that high tariffs would restore prosperity. Historians regard McKinley's victory as a realigning election in which the political stalemate of the post-Civil War era gave way to the Republican-dominated Fourth Party System, beginning with the Progressive Era. McKinley's presidency saw rapid economic growth. He promoted the 1897 Dingley Tariff to protect manufacturers and factory workers from foreign competition and, in 1900, secured the passage of the Gold Standard Act. He hoped to persuade Spain to grant independence to rebellious Cuba without conflict. Still, when negotiations failed, he requested and signed Congress's declaration of war to begin the Spanish-American War of 1898, in which the United States saw a quick and decisive victory. As part of the peace settlement, Spain turned over to the United States its main overseas colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines, while Cuba was promised independence but remained under the control of the United States Army until May 1902. In the Philippines, a pro-independence rebellion began; it was eventually suppressed. The United States annexed the independent Republic of Hawaii in 1898, and it became a United States territory in 1900. McKinley defeated Bryan again in the 1900 presidential election in a campaign focused on imperialism, protectionism, and free silver. His second term ended early when he was shot on September 6, 1901, by Leon Czolgosz, an anarchist. McKinley died eight days later and was succeeded by Vice President Theodore Roosevelt. (Wikipedia)

William McKinley (January 29, 1843 – September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party, he led a realignment that made Republicans largely dominant in the industrial states and nationwide for decades. He successfully led the U.S. in the Spanish–American War, overseeing a period of American expansionism, with the annexations of Puerto Rico, Guam, the Philippines, and Hawaii. McKinley also rejected inflationary plans such as free silver in favor of keeping the nation on the gold standard, and raised protective tariffs. McKinley was the last president to have served in the American Civil War; he was the only one to begin his service as an enlisted man and ended it as a brevet major. After the war, he settled in Canton, Ohio, where he practiced law and married Ida Saxton. In 1876, McKinley was elected to Congress, where he became the Republican expert on the protective tariff, which he believed would bring prosperity. His 1890 McKinley Tariff was highly controversial and, together with a Democratic redistricting aimed at gerrymandering him out of office, led to his defeat in the Democratic landslide of 1890. He was elected governor of Ohio in 1891 and 1893, steering a moderate course between capital and labor interests. He secured the Republican nomination for president in 1896 amid a deep economic depression and defeated his Democratic rival William Jennings Bryan after a front porch campaign in which he advocated "sound money" (the gold standard unless altered by international agreement) and promised that high tariffs would restore prosperity. Historians regard McKinley's victory as a realigning election in which the political stalemate of the post-Civil War era gave way to the Republican-dominated Fourth Party System, beginning with the Progressive Era. McKinley's presidency saw rapid economic growth. He promoted the 1897 Dingley Tariff to protect manufacturers and factory workers from foreign competition and, in 1900, secured the passage of the Gold Standard Act. He hoped to persuade Spain to grant independence to rebellious Cuba without conflict. Still, when negotiations failed, he requested and signed Congress's declaration of war to begin the Spanish-American War of 1898, in which the United States saw a quick and decisive victory. As part of the peace settlement, Spain turned over to the United States its main overseas colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines, while Cuba was promised independence but remained under the control of the United States Army until May 1902. In the Philippines, a pro-independence rebellion began; it was eventually suppressed. The United States annexed the independent Republic of Hawaii in 1898, and it became a United States territory in 1900. McKinley defeated Bryan again in the 1900 presidential election in a campaign focused on imperialism, protectionism, and free silver. His second term ended early when he was shot on September 6, 1901, by Leon Czolgosz, an anarchist. McKinley died eight days later and was succeeded by Vice President Theodore Roosevelt. (Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING

See Chapter 13: "Becoming a World Power"

29

Week 29: Tuesday, May 27, 2025

The Spanish-American War

Week 29

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – December 10, 1898) was fought between Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the U.S. acquiring sovereignty over Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, and establishing a protectorate over Cuba. It represented U.S. intervention in the Cuban War of Independence and Philippine Revolution, with the latter later leading to the Philippine–American War. The Spanish–American War brought an end to almost four centuries of Spanish presence in the Americas, Asia, and the Pacific; the United States meanwhile not only became a major world power, but also gained several island possessions spanning the globe, which provoked rancorous debate over the wisdom of expansionism. The 19th century represented a clear decline for the Spanish Empire, while the United States went from a newly founded country to a rising power. In 1895, Cuban nationalists began a revolt against Spanish rule, which was brutally suppressed by the colonial authorities. W. Joseph Campbell argues that yellow journalism in the U.S. exaggerated the atrocities in Cuba to sell more newspapers and magazines, which swayed American public opinion in support of the rebels. But historian Andrea Pitzer also points to the actual shift toward savagery of the Spanish military leadership, who adopted the brutal reconcentration policy after replacing the relatively conservative Governor-General of Cuba Arsenio Martínez Campos with the more unscrupulous and aggressive Valeriano Weyler, nicknamed "The Butcher." President Grover Cleveland resisted mounting demands for U.S. intervention, as did his successor William McKinley. Though not seeking a war, McKinley made preparations in readiness for one. In January 1898, the U.S. Navy armored cruiser USS Maine was sent to Havana to provide protection for U.S. citizens. After the Maine was sunk by a mysterious explosion in the harbor on February 15, 1898, political pressures pushed McKinley to receive congressional authority to use military force. On April 21, the U.S. began a blockade of Cuba, and soon after Spain and the U.S. declared war. The war was fought in both the Caribbean and the Pacific, where American war advocates correctly anticipated that U.S. naval power would prove decisive. On May 1, a squadron of U.S. warships destroyed the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay in the Philippines and captured the harbor. The first U.S. Marines landed in Cuba on June 10 in the island's southeast, moving west and engaging in at the Battles of El Caney and San Juan Hill on July 1 and the destroying the fleet at and capturing Santiago de Cuba on July 17. On June 20, the island of Guam surrendered without resistance, and on July 25, U.S. troops landed on Puerto Rico, which a blockade had begun on May 8 and where fighting continued until an armistice was signed on August 13. The war ended with the 1898 Treaty of Paris, signed on December 10 with terms favorable to the U.S. The treaty ceded ownership of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the U.S., and set Cuba up to become an independent state in 1902, although in practice it became a U.S. protectorate. The cession of the Philippines involved payment of $20 million ($760 million today) to Spain by the U.S. to cover infrastructure owned by Spain. In Spain, the defeat in the war was a profound shock to the national psyche and provoked a thorough philosophical and artistic reevaluation of Spanish society known as the Generation of '98.(Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING

See Chapter 13: "Becoming a World Power"

30

Week 30: Tuesday, June 3, 2025

Movies

Week 30

For our last class of the year, we will enjoy a look at the birth of movies which are created in the last decade of the 19th century.The "birth of film" is generally attributed to the Lumière brothers, who, in December 1895, presented the first commercial public screening of their Cinématographe in Paris, marking the beginning of cinema as we know it.

Here's a more detailed look at the early history of film:

Early Developments:

While the idea of capturing and projecting motion was a long time in the making, the Lumière brothers' Cinématographe was a pivotal invention.

The Lumière Brothers:

Auguste and Louis Lumière, inventors of several devices in the field of photography, invented the Cinematograph, which could take pictures, print positives, and project them onto a screen.

First Commercial Screening:

On December 28, 1895, the Lumière brothers screened ten short films at the Salon Indien du Grand Café in Paris, which is traditionally marked as the birth date of film.

The Cinématographe:

The Cinématographe was a camera, a projector, and a film printer all in one, allowing the Lumière brothers to create and project moving pictures.

Other Early Inventors:

Thomas Edison's Kinetoscope, which allowed one person at a time to view moving pictures, was also a significant early development, with public parlors established around the world by 1894.

The Edison Vitascope:

The Edison Vitascope brought projection to the United States and established the format for American film exhibition for the next several years.

All

Week 1: Wed., Oct. 9, 2024

Our First Revolution

WEEK 1

We begin our study of the American Revolution with a look back into English history. The roots of the American Revolution are to be found in the great revolutionary upheaval of 1688 in England. In that year the English people rose up again against the king (James II) who was trying to impose upon them his own personal Roman Catholic religion. The English people had made it clear in their parliament again and again that they were an Anglican nation with the religion that was their own version of Protestantism, created during the reign of Henry VIII, and did not want to join the international Roman Catholic Church. King James II tried and tried and tried to drag the nation into his own Roman Catholic beliefs. This failed in 1688, when he was pushed out of office and sent into permanent exile in France. In the years immediately succeeding this event, the English people wrote a "Bill of Rights" which was imposed upon the new Protestant monarchs William and Mary. This event and the literature that accompanied the event (John Locke) provided the intellectual and legal basis for the American Revolution a century later. The title of our lecture is taken from a wonderful book by the American political scientist Michael Barone.(Our First Revolution)

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

From the Publisher:

"For too long we’ve lacked a compact, inexpensive, authoritative, and compulsively readable book that offers American readers a clear, informative, and inspiring narrative account of their country. Such a fresh retelling of the American story is especially needed today, to shape and deepen young Americans’ sense of the land they inhabit, help them to understand its roots and share in its memories, all the while equipping them for the privileges and responsibilities of citizenship in American society. The existing texts simply fail to tell that story with energy and conviction. Too often they reflect a fragmented outlook that fails to convey to American readers the grand trajectory of their own history. A great nation needs and deserves a great and coherent narrative, as an expression of its own self-understanding and its aspirations; and it needs to be able to convey that narrative effectively. Of course, it goes without saying that such a narrative cannot be a fairy tale of the past. It will not be convincing if it is not truthful. But as Land of Hope brilliantly shows, there is no contradiction between a truthful account of the American past and an inspiring one. Readers of Land of Hope will find both in its pages."

REVIEWS

“At a time of severe partisanship that has infected many accounts of our nation’s past, this brilliant new history, Land of Hope, written in lucid and often lyrical prose, is much needed. It is accurate, honest, and free of the unhistorical condescension so often paid to the people of America’s past. This generous but not uncritical story of our nation’s history ought to be read by every American. It explains and justifies the right kind of patriotism.”― Gordon S. Wood, author of Friends Divided: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson

“We’ve long needed a readable text that truly tells the American story, neither hiding the serious injustices in our history nor soft-pedaling our nation’s extraordinary achievements. Such a text cannot be a mere compilation of facts, and it certainly could not be written by someone lacking a deep understanding and appreciation of America’s constitutional ideals and institutions. Bringing his impressive skills as a political theorist, historian, and writer to bear, Wilfred McClay has supplied the need.”― Robert P. George, McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence, Princeton University

“No one has told the story of America with greater balance or better prose than Wilfred McClay. Land of Hope is a history book that you will not be able to put down. From the moment that ‘natives’ first crossed here over the Bering Strait, to the founding of America’s great experiment in republican government, to the horror and triumph of the Civil War...McClay’s account will capture your attention while offering an unforgettable education.”― James W. Ceaser, Professor of Politics, University of Virginia

Week 2: Wed., Oct. 16, 2024

18th Century Britain

WEEK 2

The revolutionary activities that unfolded in the colonies of North America during the 1760s and 1770s were all actions taken by Englishmen. The ideas, the books, the legal arguments, of all the major revolutionaries, Samuel Adams, John Adams, John Dickinson, Ben Franklin, all of these ideas were rooted in the events in England during the 1700s. The revolutionaries in Boston had no desire to break away from their English homeland. They thought like Englishman. They wrote books rooted in English legal traditions. They responded to the latest publications in London. And they were supported in England by voices in the English parliament. Therefore, as the revolutionary movement developed in Boston, Philadelphia and Virginia, the whole movement was filled with English ideas, books, and language. In our second week we will talk about this 18th century England with its Hanoverian kings and it's brilliant legal scholars.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

RECOMMENDED BOOK

Week 3: Wed., Oct. 23, 2024

18th Century France

WEEK 3

The revolutionaries in Boston in the 1760s and 1770s were first of all Englishmen. But they read French books. They knew the literature of the French Enlightenment well, Voltaire, Montesquieu, Rousseau, and others as well as the literature coming out of England. And as the crisis evolved, everyone in Boston and Philadelphia began to realize that if there was a break with England, the one most important nation that might help the colonies was the nation of France. The French Connection was complicated by the fact that France also was going through a pre-revolutionary phase. By the 1770s, Paris was on fire with revolutionary ideas and books that were widely read. But the overriding issue for the French government was any alliance that would help them fight their traditional enemies on the British island. Therefore, some alliance between the American colonies and the French nation was obvious to all. King Louis XVI was very much in favor of French help for the American colonies. If you would like to know something about the French Revolution here is a very useful short introduction.

RECOMMENDED READING

William Doyle,

The French Revolution: A Very Short Introduction,

Oxford University Press; 1 edition (December 6, 2001),

ISBN 0192853961

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

Week 4: Wed., Oct. 30, 2024

Empire

WEEK 4

"The Seven Years’ War was particularly important to the future of America, where it came to be referred to as the French and Indian War, and would last from 1754 to 1763. The French and Indian War was enormously consequential. It would dramatically change the map of North America. It would also force a rethinking of the entire relationship between England and her colonies and bring to an end any remaining semblance of the “salutary neglect” policy. And that change, in turn, would help pave the way to the American Revolution."

McClay, Wilfred M.. Land of Hope (p. 35). Encounter Books.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

Week 5: Wed., Nov. 6, 2024

The Boston Massacre

WEEK 5

The Boston Massacre was a confrontation in Boston on March 5, 1770, in which nine British soldiers shot several of a crowd of three or four hundred who were harassing them verbally and throwing various projectiles. The event was heavily publicized as "a massacre" by leading Patriots such as Paul Revere and Samuel Adams. British troops had been stationed in the Province of Massachusetts Bay since 1768 in order to support crown-appointed officials and to enforce unpopular Parliamentary legislation. Amid tense relations between the civilians and the soldiers, a mob formed around a British sentry and verbally abused him. He was eventually supported by seven additional soldiers, led by Captain Thomas Preston, who were hit by clubs, stones, and snowballs. Eventually, one soldier fired, prompting the others to fire without an order by Preston. The gunfire instantly killed three people and wounded eight others, two of whom later died of their wounds. Depictions, reports, and propaganda about the event heightened tensions throughout the Thirteen Colonies, notably the colored engraving produced by Paul Revere which you can see below.

David McCullough on John Adams and the British soldiers arrested and accused of murder:

"Samuel Adams was quick to call the killings a 'bloody butchery' and to distribute a print published by Paul Revere vividly portraying the scene as a slaughter of the innocent, an image of British tyranny, the Boston Massacre, that would become fixed in the public mind. The following day thirty-four-year-old John Adams was asked to defend the soldiers and their captain, when they came to trial. No one else would take the case, he was informed. . . .Adams accepted, firm in the belief, as he said, that no man in a free country should be denied the right to counsel and a fair trial, and convinced, on principle, that the case was of utmost importance. As a lawyer, his duty was clear. That he would be hazarding his hard-earned reputation and, in his words, 'incurring a clamor and popular suspicions and prejudices' against him, was obvious, and if some of what he later said on the subject would sound a little self-righteous, he was also being entirely honest. Only the year before, in 1769, Adams had defended four American sailors charged with killing a British naval officer who had boarded their ship with a press gang to grab them for the British navy. The sailors were acquitted on grounds of acting in self-defense, but public opinion had been vehement against the heinous practice of impressment. Adams had been in step with the popular outrage, exactly as he was out of step now. He worried for Abigail, who was pregnant again, and feared he was risking his family’s safety as well as his own, such was the state of emotions in Boston."

McCullough, David. John Adams . Simon & Schuster.

John Adams willingness to defend these British soldiers was one of the most courageous acts of his lifetime, and although at the time of the trial Bostonians ranted and raged against him, later when the trial was over and temperatures cooled down, it became clear to the larger public that Adams was an extraordinarily brave and wise man. The trial and the acquittal set Adams apart from other Bostonian leaders.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

Week 6: Wed., Nov. 13, 2024

Lexington and Concord

WEEK 6

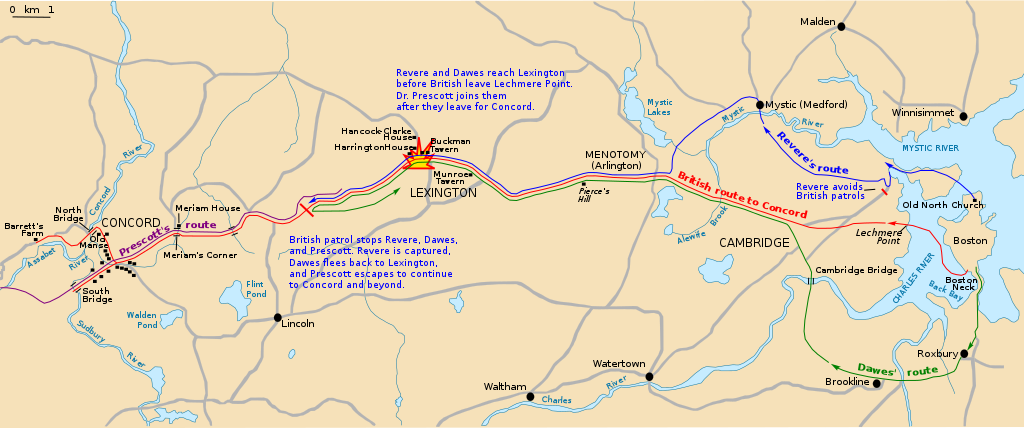

The Battles of Lexington and Concord, were the leading military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, Lincoln, Menotomy (present-day Arlington), and Cambridge. They marked the outbreak of armed conflict between the Kingdom of Great Britain and Patriot militias from America's thirteen colonies. In late 1774, Colonial leaders adopted the Suffolk Resolves in resistance to the alterations made to the Massachusetts colonial government by the British parliament following the Boston Tea Party. The colonial assembly responded by forming a Patriot provisional government known as the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and calling for local militias to train for possible hostilities. The Colonial government effectively controlled the colony outside of British-controlled Boston. In response, the British government in February 1775 declared Massachusetts to be in a state of rebellion. About 700 British Army regulars in Boston, under Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith, were given secret orders to capture and destroy Colonial military supplies reportedly stored by the Massachusetts militia at Concord. Through effective intelligence gathering, Patriot leaders had received word weeks before the expedition that their supplies might be at risk and had moved most of them to other locations. On the night before the battle, warning of the British expedition had been rapidly sent from Boston to militias in the area by several riders, including Paul Revere and Samuel Prescott, with information about British plans. The initial mode of the Army's arrival by water was signaled from the Old North Church in Boston to Charlestown using lanterns to communicate "one if by land, two if by sea". The first shots were fired just as the sun was rising at Lexington. Eight militiamen were killed, including Ensign Robert Munroe, their third in command. The British suffered only one casualty. The militia was outnumbered and fell back, and the regulars proceeded on to Concord, where they broke apart into companies to search for the supplies. At the North Bridge in Concord, approximately 400 militiamen engaged 100 regulars from three companies of the King's troops at about 11:00 am, resulting in casualties on both sides. The outnumbered regulars fell back from the bridge and rejoined the main body of British forces in Concord. The British forces began their return march to Boston after completing their search for military supplies, and more militiamen continued to arrive from the neighboring towns. Gunfire erupted again between the two sides and continued throughout the day as the regulars marched back towards Boston. Upon returning to Lexington, Lt. Col. Smith's expedition was rescued by reinforcements under Brigadier General Hugh Percy, a future Duke of Northumberland styled at this time by the courtesy title Earl Percy. The combined force of about 1,700 men marched back to Boston under heavy fire in a tactical withdrawal and eventually reached the safety of Charlestown. The accumulated militias then blockaded the narrow land accesses to Charlestown and Boston, starting the siege of Boston. Ralph Waldo Emerson describes the first shot fired by the Patriots at the North Bridge in his "Concord Hymn" as the "shot heard round the world". (Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

RECOMMENDED READING

From the Publisher:America’s beloved and distinguished historian presents, in a book of breathtaking excitement, drama, and narrative force, the stirring story of the year of our nation’s birth, 1776, interweaving, on both sides of the Atlantic, the actions and decisions that led Great Britain to undertake a war against her rebellious colonial subjects and that placed America’s survival in the hands of George Washington. In this masterful book, David McCullough tells the intensely human story of those who marched with General George Washington in the year of the Declaration of Independence—when the whole American cause was riding on their success, without which all hope for independence would have been dashed and the noble ideals of the Declaration would have amounted to little more than words on paper. Based on extensive research in both American and British archives, 1776 is a powerful drama written with extraordinary narrative vitality. It is the story of Americans in the ranks, men of every shape, size, and color, farmers, schoolteachers, shoemakers, no-accounts, and mere boys turned soldiers. And it is the story of the King’s men, the British commander, William Howe, and his highly disciplined redcoats who looked on their rebel foes with contempt and fought with a valor too little known.

Week 7: Wed., Nov. 20, 2024

Philadelphia 1775-1776

WEEK 7

The Second Continental Congress was the 1775-76 meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolution and its associated Revolutionary War that established American independence from the British Empire. The Congress created a new country that it first named the United Colonies, and in 1776, renamed the United States of America. The Congress began convening in Philadelphia, on May 10, 1775, with representatives from 12 of the 13 colonies, after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. The Second Continental Congress succeeded the First Continental Congress, which also met in Philadelphia from September 5 to October 26, 1774. The Second Congress functioned as the de facto national government at the outset of the Revolutionary War by raising militias, directing strategy, appointing diplomats, and writing petitions such as the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms and the Olive Branch Petition. All 13 colonies were represented by the time the Congress adopted the Lee Resolution, which declared independence from Britain on July 2, 1776, and the Congress unanimously agreed to the Declaration of Independence two days later. Congress functioned as the provisional government of the United States of America through March 1, 1781. During this period, it successfully managed the war effort, drafted the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, adopted the first U.S. constitution, secured diplomatic recognition and support from foreign nations, and resolved state land claims west of the Appalachian Mountains. Many of the delegates who attended the Second Congress had also attended the First. They again elected Peyton Randolph as president of the Congress and Charles Thomson as secretary. Notable new arrivals included Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania and John Hancock of Massachusetts. Within two weeks, Randolph was summoned back to Virginia to preside over the House of Burgesses; Hancock succeeded him as president, and Thomas Jefferson replaced him in the Virginia delegation. The number of participating colonies also grew, as Georgia endorsed the Congress in July 1775 and adopted the continental ban on trade with Britain. (Wikipedia)(/p>

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

RECOMMENDED READING

From the Publisher:America’s beloved and distinguished historian presents, in a book of breathtaking excitement, drama, and narrative force, the stirring story of the year of our nation’s birth, 1776, interweaving, on both sides of the Atlantic, the actions and decisions that led Great Britain to undertake a war against her rebellious colonial subjects and that placed America’s survival in the hands of George Washington. In this masterful book, David McCullough tells the intensely human story of those who marched with General George Washington in the year of the Declaration of Independence—when the whole American cause was riding on their success, without which all hope for independence would have been dashed and the noble ideals of the Declaration would have amounted to little more than words on paper. Based on extensive research in both American and British archives, 1776 is a powerful drama written with extraordinary narrative vitality. It is the story of Americans in the ranks, men of every shape, size, and color, farmers, schoolteachers, shoemakers, no-accounts, and mere boys turned soldiers. And it is the story of the King’s men, the British commander, William Howe, and his highly disciplined redcoats who looked on their rebel foes with contempt and fought with a valor too little known.

RECOMMENDED READING

Pauline Maier,

American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence,

Vintage,

ISBN 978-0679779087

NEXT WEEK IS THANKSGIVING WEEK

NO CLASSES ALL WEEK OF NOV 25-29 2024

Week 8: Wed., Dec. 4, 2024

Ben Franklin in Paris

WEEK 8

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

RECOMMENDED READING

Walter Isaacson,

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life,

Simon & Schuster (June 1, 2004),

ISBN 978-0743258074

Week 9: Wed., Dec. 11, 2024

Washington at War

WEEK 9

George Washington: ""I have often thought how much happier I should have been if, instead of accepting a command under such circumstances, I should have taken my musket upon my Shoulder & entered the Ranks or … had retir'd to the back country & lived in a Wig-wam."

—George Washington to Joseph Reed, 14 January 1776

WASHINGTON'S WAR BEGINS IN BOSTON SUMMER 1775

The siege of Boston (April 19, 1775 – March 17, 1776) was the opening phase of the American Revolutionary War. New England militiamen prevented the British Army from moving by land, and it was garrisoned in Boston, Massachusetts Bay. Both sides had to deal with resource, supply, and personnel issues over the course of the siege. British resupply and reinforcement was limited to sea access, which was impeded by American vessels. The British abandoned Boston after 11 months and transferred their troops and equipment to Nova Scotia. The siege began on April 19 after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, when Massachusetts militias blocked land access to Boston. The Continental Congress formed the Continental Army from the militias involved in the fighting and appointed George Washington as Commander in Chief. In June 1775, the British seized Bunker Hill, from which the Continentals were preparing to bombard the city, but their casualties were heavy and their gains insufficient to break the Continental Army's control over land access to Boston. After this, the Americans laid siege to the city; no major battles were fought during this time, and the conflict was limited to occasional raids, minor skirmishes, and sniper fire. British efforts to supply their troops were significantly impeded by the smaller but more agile American forces operating on land and sea, and the British consequently suffered from a continual lack of food, fuel, and supplies. In November 1775, George Washington sent Henry Knox on a mission to bring the heavy artillery that had recently been captured at Fort Ticonderoga. In a technically complex and demanding operation, Knox brought the cannons to Boston in January 1776, and this artillery fortified Dorchester Heights which overlooked Boston harbor. This development threatened to cut off the British supply lifeline from the sea. British commander William Howe saw his position as indefensible, and he withdrew his forces from Boston to Halifax, Nova Scotia on March 17.

WASHINGTON IN NEW YORK

David McCullough, 1776: "At Boston, Washington had known exactly where the enemy was, and who they were, and what was needed to contain them. At Boston the British had been largely at his mercy, and especially once winter set it. Here, with their overwhelming naval might and absolute control of the waters, they could strike at will and from almost any direction. The time and place of the battle would be entirely their choice, and this was the worry overriding all others….At Boston, Washington had benefited from a steady supply of valuable intelligence coming out of the besieged town, while Howe had known little or nothing of Washington's strengths or intentions. Here, with so much of the population still loyal to the king, the situation was the reverse." Washington: "The designs of the Enemy are too much behind the Curtain for me to form any accurate opinion of their Plan of operations… we are left to wander in the field of conjecture."

The British at New York: Joseph Ellis: "In a nearly miraculous burst of logistical energy, Great Britain assembled a fleet of 427 ships equipped with 1,200 cannons to transport 32,000 soldiers and 10,000 sailors across the Atlantic. It was the largest amphibious operation ever attempted by any European power, with an attack force larger than the population of Philadelphia, the biggest city in America" Last to arrive at New York, "was Admiral Richard Howe with by far the largest fleet, more than 150 ships with 20,000 troops and a six-month supply of food and munitions, by itself the largest armada to cross the Atlantic before the American Expeditionary Force in WWI."

This sketch by a British officer on Staten Island shows part of the king’s fleet anchored in the Narrows, across from Long Island on July 12, 1776. Admiral Howe’s flagship, Eagle, can be seen in the middle distance, approaching from the open sea.

REQUIRED READING FOR THE WHOLE YEAR OF HISTORY OF THE USA

RECOMMENDED READING

From the Publisher:In Washington: A Life celebrated biographer Ron Chernow provides a richly nuanced portrait of the father of our nation. With a breadth and depth matched by no other one-volume life of Washington, this crisply paced narrative carries the reader through his troubled boyhood, his precocious feats in the French and Indian War, his creation of Mount Vernon, his heroic exploits with the Continental Army, his presiding over the Constitutional Convention, and his magnificent performance as America's first president. Despite the reverence his name inspires, Washington remains a lifeless waxwork for many Americans, worthy but dull. A laconic man of granite self-control, he often arouses more respect than affection. In this groundbreaking work, based on massive research, Chernow dashes forever the stereotype of a stolid, unemotional man. A strapping six feet, Washington was a celebrated horseman, elegant dancer, and tireless hunter, with a fiercely guarded emotional life. Chernow brings to vivid life a dashing, passionate man of fiery opinions and many moods. Probing his private life, he explores his fraught relationship with his crusty mother, his youthful infatuation with the married Sally Fairfax, and his often conflicted feelings toward his adopted children and grandchildren. He also provides a lavishly detailed portrait of his marriage to Martha and his complex behavior as a slave master. At the same time, Washington is an astute and surprising portrait of a canny political genius who knew how to inspire people. Not only did Washington gather around himself the foremost figures of the age, including James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson, but he also brilliantly orchestrated their actions to shape the new federal government, define the separation of powers, and establish the office of the presidency. In this unique biography, Ron Chernow takes us on a page-turning journey through all the formative events of America's founding. With a dramatic sweep worthy of its giant subject, Washington is a magisterial work from one of our most elegant storytellers.

RECOMMENDED READING

David Hackett Fischer,

Washington's Crossing (Pivotal Moments in American History),

Oxford University Press; Reprint edition (February 1, 2006),

ISBN 978-0195181593

Week 10: Wed., Dec. 18, 2024

Peace of Paris 1783

WEEK 10

1773 Dec. 16, Boston Tea Party

1774 Jan, Boston under British lockdown

1775 April 19, Battle of Lexington & Concord

1775 June 17 Battle of Bunker Hill

1775 July George Washington takes command in Boston

1775 Nov. Henry Knox goes to Ticonderoga for guns

1776 Jan. Knox and guns arrive at Boston

1776 Jan. Thomas Paine publishes "Common Sense"

1776 Mar. Washington puts guns on Dorchester Heights

1776 March 17 British evacuate Boston

1776 July British arrive in New York

1776 July 4, Declaration of Independence

1776 Aug. 27 Battle of Brooklyn Washington defeated

1776 Nov. 16 Washington loses New York

1776 Dec. 25/26 Washington wins Battle of Trenton

1777 Jan. 3, Washington wins Battle of Princeton

1777 Sept 19-Oct 7, Americans win Battle of Saratoga; brings in French aid

1778 Feb. 6, French-American alliance announced

1778 June 28, Battle of Monmouth, Geo Washington saves the day

1779 Feb. 3, Battle of Port Royal Island SC

1779 Nov Washington’s Main Army begins camping at Morristown, NJ

1780 Oct 7, Americans win Battle of Kings Mountain;

Thomas Jefferson called the battle "The turn of the tide of success."

1781 Mar 2, Articles of Confederation adopted

1781 Sep 28-Oct 19 - Siege of Yorktown, VA

1781 Oct 19, General Cornwallis officially surrenders at Yorktown, VA

1783 Sept 3, US and British sign Treaty of Paris

RECOMMENDED READING

The Chernow biography is the best source for the later war and its conclusion.