Week 2

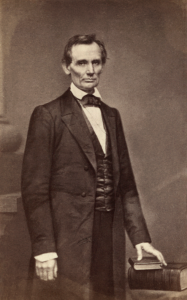

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

People who knew Lincoln, wrote J. G. Holland, an early biographer who interviewed dozens of associates and intimates in the months after his death, said that "he was one of the saddest men that ever lived, and that he was one of the jolliest men that ever lived; that he was very religious, but that he was not a Christian; … that he was the most cunning man in America, and that he had not a particle of cunning in him; that he had the strongest personal attachments, and that he had no personal attachments at all; … that he was a tyrant, and that he was the softest-hearted, most brotherly man that ever lived; … that he was a leader of the people, and that he was led by the people; that he was cool and impassive, and that he was susceptible of the strongest passions." It's of course a cliché to say that some great figure in our history was "a bundle of contradictions." But the fact that so many people held such different and indeed contradictory opinions about him is already suggestive of the complexity of his character

It is hardly a news flash to say that Abraham Lincoln was our greatest President. But what do we mean by "greatness"? It's a term that historians, who spend much of their time debunking reputations, are reluctant to use, because it lacks precision. But let's begin by acknowledging that Lincoln, like Churchill in the following century, (1) changed the course of history by saving a beleaguered democracy; (2) that in the dire circumstances in which he found himself in 1861, only he could have done this (again, like Churchill in 1940); and (3) that his extraordinary character as a leader depended not simply on excellence in one sphere of activity but in multiple roles, including the ability to articulate unforgettably the meaning of the struggle in which he and his people were engaged. Here, too, in his mastery of all the resources of the English language, Churchill resembled him. But there was a difference: Churchill was an aristocrat, born in a palace; Lincoln, as everybody knows, was born in a log cabin and almost entirely self-taught.

PROF. BRUCE THOMPSON

THE LINCOLN-DOUGLAS DEBATES

The most famous debates in American political history focused almost exclusively on the issue that divided Americans most bitterly and threatened the very integrity of their nation: slavery. Douglas defended his doctrine of popular sovereignty: he endorsed the decision of the citizens of Illinois to abolish slavery in their own state, but argued that what the people of other states and territories decided to do about slavery was their own business. He accused Lincoln, no longer a Whig, of being a "black Republican" who placed the interests of black slaves and his own political aspirations above the integrity of the Union. He backed Lincoln into a corner and forced him to declare himself in some respects at least a white supremacist. Lincoln fought back by attacking not only Douglas's doctrine of popular sovereignty but also the Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision of the previous year, which stated that no black person could be a citizen, that owning slaves was an inviolable right of property, and that the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and the Missouri Compromise of 1820 had violated the Fifth Amendment's prohibition against taking property without due process. If slave ownership was a constitutionally protected property right, how could territorial settlers legally exclude slavery? The Court, he said, had watered down Douglas's popular sovereignty doctrine until it was "as thin as the homeopathic soup that was made by boiling the shadow of a pigeon that had starved to death." Douglas replied that the people of a territory could override the Supreme Court by refusing to pass a slave code, but Lincoln pointed out that if this "lawless" doctrine were accepted then abolitionists by the same logic could refuse to enforce the fugitive slave clause of the Constitution. Lincoln, in other words, showed that Douglas's doctrine of popular sovereignty and Chief Justice Taney's decision that the Constitution endorsed slavery as an inviolable right of property, were logically incompatible with each other. But Lincoln went further, and deeper. Did Douglas deny that black slaves were human beings? Did he maintain that they had no rights at all? Lincoln famously argued that although all men were not created equal in every respect, they were equal in at least one respect: that they were entitled to a share in the fruits of their own labor. Conceding that the African American was "perhaps" not the equal of the white American in some respects, he insisted that in the right to put into his mouth the bread that he had earned with his own hands, he is the equal of every other man.

PROF. BRUCE THOMPSON

RECOMMENDED READING

Destined to become a classic in American history and biography, David Herbert Donald’s Lincoln is a masterly account of how one man’s extraordinary political acumen steered the Union to victory in the Civil War, and of how his soaring rhetoric gave meaning to that agonizing struggle for nationhood and equality. This fully rounded biography of America’s sixteenth President is the product of Donald’s half-century of study of Lincoln and his times. In preparing it, Donald has drawn more extensively than any previous writer on Lincoln’s personal papers and those of his contemporaries, and he has taken full advantage of the voluminous newly discovered records of Lincoln’s legal practice. He presents his findings with the same literary skill and psychological understanding exhibited in his previous biographies, which have received two Pulitzer Prizes. Donald brilliantly traces Lincoln’s rise from humble origins in Kentucky to prominent positions in legal and political circles in Illinois, and then to the pinnacle of the presidency. He shows how, in all these roles, Lincoln repeatedly demonstrated his enormous capacity for growth, which enabled one of the least experienced and most poorly prepared men ever elected to high office to become a giant in the annals of American politics. Much more than a political biography, Donald’s Lincoln reveals the development of the future President’s character and shows how his private life helped to shape his public career.

RECOMMENDED READING

Michael Burlingame,

Abraham Lincoln: A Life,

Johns Hopkins University Press; Abridged edition (October 10, 2023),

ISBN 978-1421445557

(For best deal, OK to purchase used hardcover from Amazon)