Week 1

Week 1: Tuesday, October 11, 2022

Russia Before the Russians

Week 1

"Russian history begins with the polity that scholars have come to call Kiev Rus, the ancestor of modern Russia. Rus was the name that the inhabitants gave to themselves and their land, and Kiev was its capital. In modern terms, it embraced all of Belarus, the northern half of the Ukraine, and the center and northwest of European Russia. The peoples of these three modern states are the Eastern Slavs, who all speak closely related languages derived from the East Slavic language of Kiev Rus. In the west its neighbors were roughly the same as the neighbors of those three states today: Hungary, Poland, the Baltic peoples, and Finland. In the north Kiev Rus stretched toward the Arctic Ocean, with Slavic farmers only beginning to move into the far north. Beyond the Slavs to the east was Volga Bulgaria, a small Turkic Islamic state that came into being in about AD 950 where modern Tatarstan stands today. Beyond Volga Bulgaria were the Urals and Siberia, vast forests and plains inhabited by small tribes who lived by hunting and gathering food. The core of Kiev Rus was along the route that ran from northern Novgorod south to Kiev along the main rivers. There in the area of richest soil lay the capital, Kiev. Even farther to the south of Kiev began the steppe." Bushkovitch, Paul. A Concise History of Russia (Cambridge Concise Histories) (p. 1). Cambridge University Press.

REQUIRED READING

The book below is our year-long history book that we will all use. You will be very grateful as we proceed, to have this succinct, well-organized volume available. It is part of the Concise History series at Cambridge University Press. Please buy it using this link so that the Institute gets a little financial credit for the purchase.

Review

"For any student trying to get a grasp of the essentials of Russian history this book is the place to start. To cover everything from the origins of the Russian people to the collapse of the Soviet Union in one short book requires great skill, but Paul Bushkovitch is one of the leading experts on Russian history in the world and he manages this task with great insight and panache."

Dominic Lieven, Trinity College, Cambridge University

"This is a lively and readable account, covering more than a thousand years of Russian history in an authoritative narrative. The author deals perceptively not only with political developments, but also with those aspects of modern Russian culture and science that have had an international impact."

Maureen Perrie, University of Birmingham

"If you want to understand Russia, and the story of the Russians, you can do no better than Paul Bushkovitch’s A Concise History of Russia. Bushkovitch has performed a minor miracle: he’s told the remarkably complicated, convoluted, and controversial tale of Russian history simply, directly, and even-handedly. He doesn’t get mired in the details, lost in the twists and turns, or sidetracked by axe grinding. He tells you what happened and why, full stop. So if you want to know what happened and why in Russian history, you be advised to begin with Bushkovitch's masterful introduction."

Marshall Poe, University of Iowa

2

Week 2: Tuesday, October 18, 2022

Kievan Rus

Week 2

Kievan Rus was a loose federation of East Slavic and Uralic peoples in Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century, under the reign of the Rurik dynasty, founded by the Varangian prince Rurik. The modern nations of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine all claim Kievan Rus as their cultural ancestors, with Belarus and Russia deriving their names from it. The Rurik dynasty would continue to rule parts of Rus' until the 16th century with the Tsardom of Russia. At its greatest extent, in the mid-11th century, it stretched from the White Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south and from the headwaters of the Vistula in the west to the Taman Peninsula in the east, uniting the majority of East Slavic tribes. According to Rus Primary Chronicle, the first ruler to start uniting East Slavic lands into what has become known as Kievan Rus was Prince Oleg (879–912). He extended his control from Novgorod south along the Dnieper river valley to protect trade from Khazar incursions from the east, and moved his capital to the more strategic Kiev.

Also, we should take note of the neighboring Bulgarians at the same period. Csar Simeon I the Great ruled over Bulgaria from 893 to 927, during the First Bulgarian Empire. Simeon's successful campaigns against the Byzantines, Magyars and Serbs led Bulgaria to its greatest territorial expansion ever, making it the most powerful state in contemporary Eastern and Southeast Europe. His reign was also a period of unmatched cultural prosperity and enlightenment later deemed the Golden Age of Bulgarian culture. During Simeon's rule, Bulgaria spread over a territory between the Aegean, the Adriatic and the Black Sea. The newly independent Bulgarian Orthodox Church became the first new patriarchate besides the Pentarchy, and Bulgarian Glagolitic and Cyrillic translations of Christian texts spread all over the Slavic world of the time. It was at the Preslav Literary School in the 890s that the Cyrillic alphabet was developed. Halfway through his reign, Simeon assumed the title of Emperor (Csar), having prior to that been styled Prince.

REQUIRED READING

3

Week 3: Tuesday, October 25, 2022

Christians Come to Russia

Week 3

"The moment the first East Slavic state—the precursor of today’s Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus—began to coalesce was the same moment of its Christianization a thousand years ago. Therefore, Christianity has been central to Russian culture throughout its history."

ScotT Kenworthy, Understanding World Christianity: Russia 5 (p. 63). Fortress Press

The church tradition of Georgia and Ukraine regards Saint Andrew as the first preacher of Christianity in the territory of Georgia and Ukraine and as the founder of the Georgian and Ukraine church. This tradition was apparently derived from the Byzantine sources, particularly Nicetas of Paphlagonia (died c. 890) who asserts that "Andrew preached to the Iberians, Sauromatians, Taurians, and Scythians and to every region and city, on the Black Sea, both north and south." This version was adopted by the 10th–11th-century Georgian ecclesiastics and, refurbished with more details, was inserted in the Georgian Chronicles. The story of Saint Andrew's mission in the Georgian lands endowed the Georgian church with apostolic origin and served as a defence argument to George the Hagiorite against the encroachments from the Antiochian church authorities on the Georgian church. The Georgian Orthodox Church marks two feast days in honor of Saint Andrew, on 12 May and 13 December. The former date, dedicated to Saint Andrew's arrival in Georgia, is a public holiday in Georgia.

REQUIRED READING

RECOMMENDED READING

Scott Kenworthy,

Understanding World Christianity: Russia,

Fortress Press (January 19, 2021),

ISBN 1451472501

Editorial Reviews

"Written by two of the world's leading scholars of Russian Orthodoxy, this splendid volume fills a huge gap in the literature of World Christianity. Kenworthy and Agadjanian's skillful overview balances theological traditions and historical developments with nuanced treatment of contemporary issues. Accessible to broad audiences, and also useful for specialists, it introduces the rich devotional and institutional life of Russia's majority Christian tradition. I recommend it very highly." --Dana L. Robert, Truman Collins Professor of World Christianity and History of Mission, Boston University

"This powerful and engaging book provides clear-headed knowledge about Russian Orthodoxy, its faith and religious practice, its aspirations and fears. No one could read this book without gaining understanding and insight. A wonderful book! Essential reading!" --Archpriest Andrew Louth FBA, Professor Emeritus, University of Durham, UK

"In this luminously written study we have a most beautiful introduction to Russian Christianity that is at once masterly in its coverage and also deeply fascinating in its level of detail." --John A. McGuckin, Oxford University Faculty of Theology

"This excellent guide to Russian Orthodoxy is much needed, as the subject is poorly understood, even by many experts on Russia. Kenworthy sums up lucidly the serious research done by scholars in recent years, and displays the Orthodox Church in all its spiritual, theological, geographic and ethnic diversity." --Geoffrey Hosking, Emeritus Professor of Russian History, University College London

"This compact study of Christianity in Russia, by leading historian Scott Kenworthy and historical sociologist Alexander Agadjanian, provides a systematic and sophisticated account of Christianity in Russia from its medieval origins to the present day. It is a state-of-the-art piece of scholarship, reflecting the massive research in Russia and abroad since the collapse of the Soviet Union moved the study of religion to the front burner. Specialists and non-specialists will profit from a close reading of this important volume." --Gregory Freeze, Brandeis University

4

Week 4: Tuesday, November 1, 2022

Mongolians

Week4

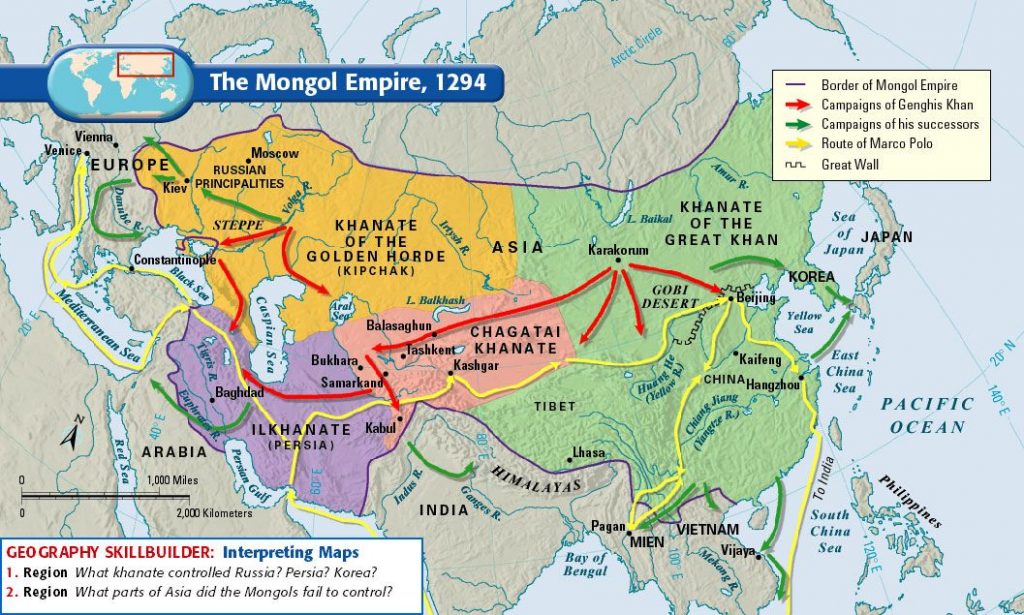

"After the gradual disintegration of Kiev Rus, the regional powers that supplanted it began to grow apart. In these centuries the territories of Novgorod and the old northeast began to form a distinct language and culture that we can call Russian. Though the older term Rus persisted until replaced by Russia (Rossiia) in the fifteenth century, for this period we may begin to call the area Russia and the people Russian. In these centuries, Russia, like the other territories of Kiev Rus that would fall to Lithuania, experienced a cataclysm in the form of the Mongol invasion, one that shaped its history for the next three centuries. The Mongol Empire was the last and largest of the nomadic empires formed on the Eurasian steppe. It was largely the work of Temuchin, a Mongolian chieftain who united the Mongolian tribes in 1206 and took the name of Genghis Khan. In his mind, the Eternal Blue Heaven had granted him rule over all people who lived in felt tents, and he was thus the legitimate ruler of all inner Asian nomads. The steppe was not enough. In 1211 Genghis Khan moved south over the Great Wall and overran northern China. His armies then swept west, and by his death in 1227, they had added all of Inner and Central Asia to their domains." Bushkovitch, Paul. A Concise History of Russia (Cambridge Concise Histories) (p. 19). Cambridge University Press.

REQUIRED READING

5

Week 5: Tuesday, November 8, 2022

The Birth of Russia

Week 5

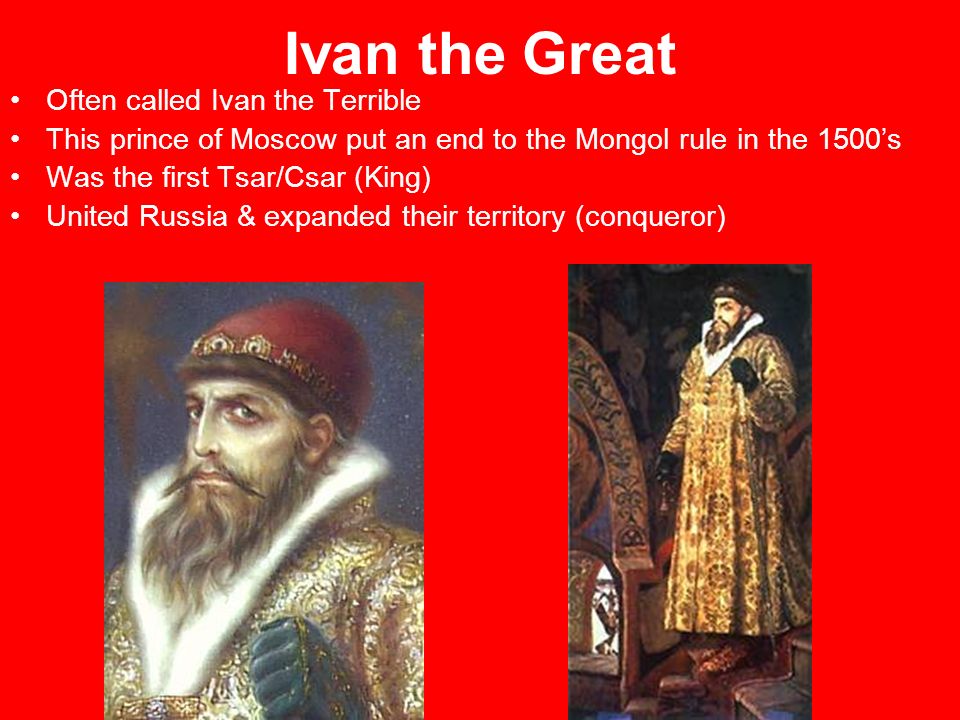

"At the end of the fifteenth century, Russia came into being as a state – no longer just a group of related principalities. Precisely at this time in written usage the modern term Rossia (a literary expression borrowed from Greek) began to edge out the traditional and vernacular Rus. If we must choose a moment for the birth of Russia out of the Moscow principality, it is the final annexation of Novgorod by Grand Prince Ivan III (1462–1505) of Moscow in 1478. By this act, Ivan united the two principal political and ecclesiastical centers of medieval Russia under one ruler, and in the next generation he and his son Vasilii III (1505–1533) added the remaining territories. In the west and north, the boundaries they established are roughly those of Russia today, while in the south and east the frontier for most of its length remained the ecological boundary between forest and steppe. In spite of later expansion, this territory formed the core of Russia until the middle of the eighteenth century, and it contained most of the population and the centers of state and church. The Russians were still a people scattered along the rivers between great forests." Bushkovitch, Paul. A Concise History of Russia (Cambridge Concise Histories) (p. 37). Cambridge University Press.

REQUIRED READING

6

Week 6: Tuesday, November 15, 2022

Boris Godunov

Week 6

"On Ivan’s death the country was slowly recovering from the disasters of the last twenty-five years of his reign. He had two surviving sons, the eldest Fyodor from Anastasiia and Dmitrii (born 1582) from his fourth wife, Mariia Nagaia. Fyodor, who appears to have been limited in both abilities and health, was married to Irina Godunov, the sister of Boris Godunov, a boyar who had risen from modest origins in the landholding class through the Oprichnina. With the accession of his brother-in-law to the throne, Boris was now in a position to become the dominant personality around the tsar. First, however, he had to get rid of powerful boyar rivals who saw their chance to restore their power at the court. Indeed at the beginning of Fyodor’s reign virtually every boyar clan that had suffered under Ivan returned to the duma if they had not already done so. Boris lost no time in marginalizing them one by one and forcing some into exile. His second problem was the presence of the tsarevich Dmitrii, for Fyodor and Irina had only a daughter who died in infancy." Bushkovitch, Paul. A Concise History of Russia (Cambridge Concise Histories) (pp. 53-54). Cambridge University Press.

REQUIRED READING

THANKSGIVING NEXT WEEK NO CLASS

7

Week 7: Tuesday, November 29, 2022

Tsar Michael

Week 7

Michael I (Mikhaíl Fyodorovich Románov) (1596 – 1645) became the first Russian Tsar of the House of Romanov after the zemskiy sobor of 1613 elected him to rule the Czardom of Russia. He was the son of Feodor Nikitich Romanov (later known as Patriarch Filaret) and of Xenia (later known as "the great nun" Martha). He was also a first cousin once removed of the last Rurikid Czar Feodor I through his great-aunt Anastasia Romanovna, who was the mother of Feodor I, and through marriage, a great-nephew in-law with Czar Ivan IV of Russia. His accession marked the end of the "Time of Troubles". During his reign, Russia conquered most of Siberia, largely with the help of the Cossacks and the Stroganov family. Russia had extended to the Pacific Ocean by the end of Michael's reign. Michael's grandfather, Nikita, was brother to the first Russian Tsaritsa Anastasia and a central advisor to Ivan the Terrible. As a young boy, Michael and his mother had been exiled to Beloozero in 1600. This was a result of the recently elected Tsar Boris Godunov, in 1598, falsely accusing his father, Feodor, of treason. This may have been partly because Feodor had married Ksenia Shestova against Boris' wishes. Michael was unanimously elected Tsar of Russia by a national assembly on 21 February 1613, but the delegates of the council did not discover the young Tsar and his mother at the Ipatiev Monastery near Kostroma until 24 March. He had been chosen after several other options had been removed, including royalty of Poland and Sweden. Initially, Martha protested, believing and stating that her son was too young and tender for so difficult an office, and in such a troublesome time. (Wikipedia)

Michael I (Mikhaíl Fyodorovich Románov) (1596 – 1645) became the first Russian Tsar of the House of Romanov after the zemskiy sobor of 1613 elected him to rule the Czardom of Russia. He was the son of Feodor Nikitich Romanov (later known as Patriarch Filaret) and of Xenia (later known as "the great nun" Martha). He was also a first cousin once removed of the last Rurikid Czar Feodor I through his great-aunt Anastasia Romanovna, who was the mother of Feodor I, and through marriage, a great-nephew in-law with Czar Ivan IV of Russia. His accession marked the end of the "Time of Troubles". During his reign, Russia conquered most of Siberia, largely with the help of the Cossacks and the Stroganov family. Russia had extended to the Pacific Ocean by the end of Michael's reign. Michael's grandfather, Nikita, was brother to the first Russian Tsaritsa Anastasia and a central advisor to Ivan the Terrible. As a young boy, Michael and his mother had been exiled to Beloozero in 1600. This was a result of the recently elected Tsar Boris Godunov, in 1598, falsely accusing his father, Feodor, of treason. This may have been partly because Feodor had married Ksenia Shestova against Boris' wishes. Michael was unanimously elected Tsar of Russia by a national assembly on 21 February 1613, but the delegates of the council did not discover the young Tsar and his mother at the Ipatiev Monastery near Kostroma until 24 March. He had been chosen after several other options had been removed, including royalty of Poland and Sweden. Initially, Martha protested, believing and stating that her son was too young and tender for so difficult an office, and in such a troublesome time. (Wikipedia)

A NOTE ON CZAR VERSUS TSAR:

Tsar also spelled czar, tzar, or csar, is a title used to designate East and South Slavic monarchs or supreme rulers of Eastern Europe, originally the Bulgarian monarchs from 10th century onwards, much later a title for two rulers of the Serbian Empire, and from 1547 the supreme ruler of the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire. In this last capacity it lends its name to a system of government, tsarist autocracy or tsarism. The term is derived from the Latin word caesar, which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the term—a ruler with the same rank as a Roman emperor, holding it by the approval of another emperor or a supreme ecclesiastical official (the Pope or the Ecumenical Patriarch)—but was usually considered by western Europeans to be equivalent to king, or to be somewhat in-between a royal and imperial rank.

"Tsar" and its variants were the official titles of the following states:

Bulgarian Empire (First Bulgarian Empire in 919–1018, Second Bulgarian Empire in 1185–1396)

Serbian Empire, in 1346–1371

Tsardom of Russia, in 1547–1721 (replaced in 1721 by imperator in Russian Empire, but still remaining in use, also officially in relation to several regions until 1917)

The first ruler to adopt the title tsar was Simeon I of Bulgaria.

REQUIRED READING

8

Week 8: Tuesday, December 6, 2022

Peter the Great

Week 8

"The reign of Peter the Great saw the greatest transformation in Russia until the revolution of 1917. Unlike the Soviet revolution, Peter’s transformation of Russia had little impact on the social order, for serfdom remained and the nobility remained their masters. What Peter changed was the structure and form of the state, turning the traditional Russian tsardom into a variant of European monarchy. At the same time he profoundly transformed Russian culture, a contribution that along with his new capital of St. Petersburg has lasted to the present day." Bushkovitch, Paul. A Concise History of Russia (Cambridge Concise Histories) (p. 79). Cambridge University Press.

REQUIRED READING

RECOMMENDED READING

9

Week 9: Tuesday, December 13, 2022

Two Empresses

Week 9

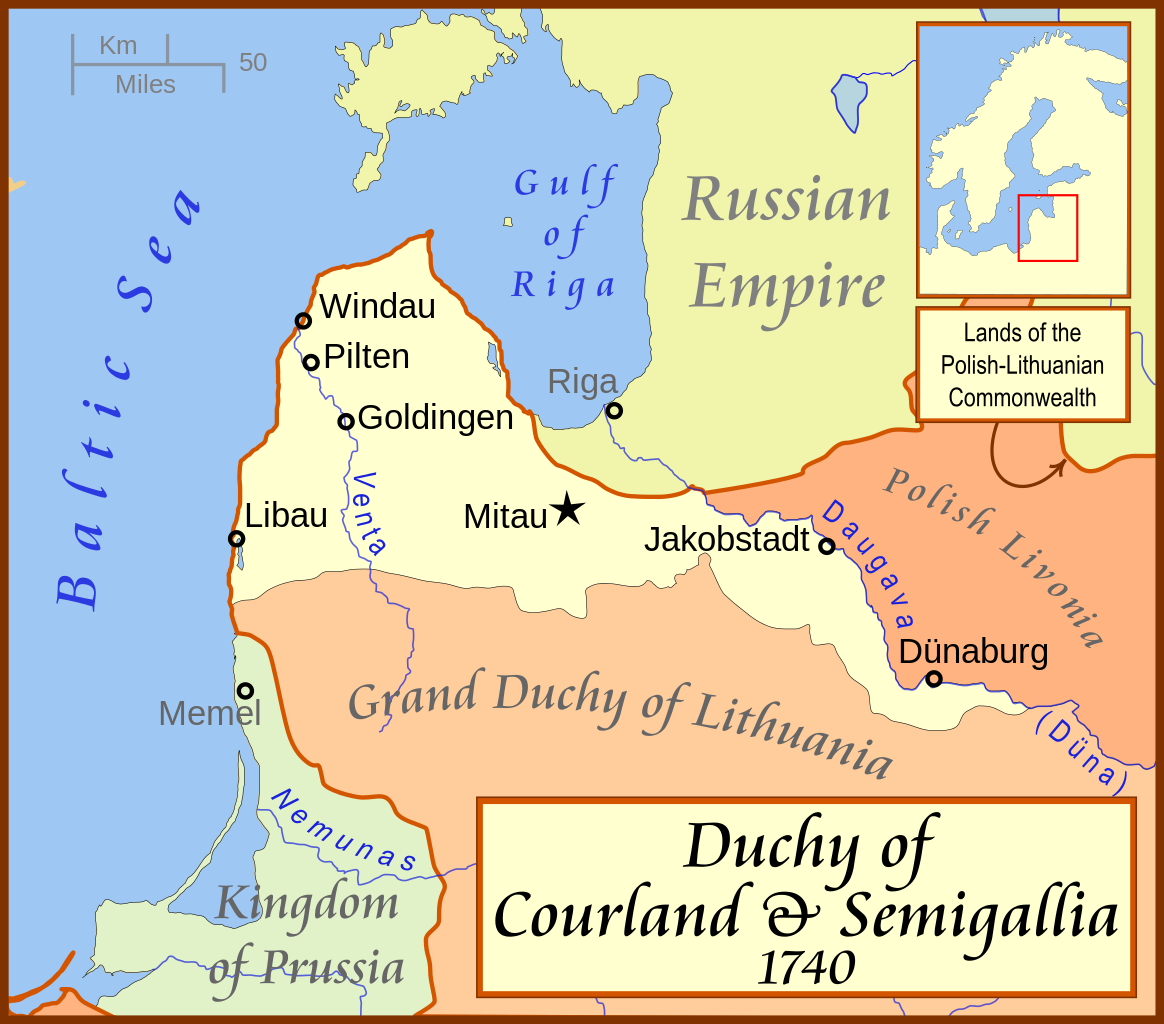

"With the restoration of autocracy, Duchess Anna of Courland came to the throne as Empress of Russia, and after a time she sent the leaders of the Golitsyn and Dolgorukii clans into exile. The ten years of Anna’s reign in the memory of the Russian nobility was a dark period of rule by Anna’s German favorites – particularly her chamberlain – Ernst-Johann Bühren (Biron to the Russians), who was allegedly all-powerful and indifferent to Russian interests. That memory was a considerable exaggeration. After a brief interlude, Empress Elizabeth, Peter the Great’s daughter and a capable and strong monarch succeeded her (1741–1761). Underneath all the drama at court, Russia’s new culture took shape, and Russia entered the age of the Enlightenment. In these decades we can also get a glimpse of Russian society that goes beyond descriptions of legal status into the web of human relations. Politically Anna’s court was not a terribly pleasant place, though the story of “German domination” is largely a legend. Anna was personally close to Biron, who had served her well in Courland, where she had lived since the death of her husband the duke in 1711. She entrusted foreign policy to Count Andrei Ostermann and the army to Count Burkhard Christian Münnich, but the three were in no sense a clique. Indeed, they hated one another and made alliances with the more numerous Russian grandees in the court and in the government. The truth was that Anna relied on them and a few others and she did not consult with the elite as a whole. The Senate languished. Not surprisingly, Anna was terrified that there would be plots against her in favor of Elizabeth, Peter’s eldest surviving daughter, or other candidates for the throne" Bushkovitch, Paul. A Concise History of Russia (Cambridge Concise Histories) (pp. 101-102). Cambridge University Press.

You can see in the map below, the the Duchy of Courland would be in Lithuania today. But in the 18th century, its position on the border of Prussia, Lithuania, and Russia made it a valuable prize.

REQUIRED READING

RECOMMENDED READING

This book about Frederick the Great helps the reader understand much of Russian history since Frederick is in the background of all the maneuvering inside the Russian court.

10

Week 10: Tuesday, December 20, 2022

Young Catherine

Week 10

Empress Elizabeth makes plans for a successor and finds this young man a wife from Germany: this is the future Catherine the Great called Sophie when she first came to Russia with her mother in 1744.

"Empress Elizabeth, like her predecessor Anna, had to provide for a succession to her throne, as she had no children of her own. She chose her nephew, Karl Peter Ulrich, the Duke of Holstein-Gottorp and the son of her older sister Anna Petrovna, who had married the then Duke in 1725. Elizabeth’s idea was to keep the succession in her family, not in the family of Empress Anna. The Holstein connection also had diplomatic advantages in relation to Sweden and the German states, especially Prussia. Elizabeth brought the boy to Russia in 1742 with a large suite of Holsteiners and he converted to Orthodoxy with the name Peter in honor of his grandfather, Peter the Great. The young Peter was not a particularly promising boy, and Elizabeth decided that he needed a wife. She chose Sophie, the daughter of the Duke of Anhalt-Zerbst – Anhalt-Zerbst being a small German principality in the Prussian orbit. Sophie’s mother was also from the Holstein family, so that Sophie and Peter were cousins and were both related to the then King of Sweden. The family also had the support of Frederick the Great of Prussia, victorious in war with Austria (1740–1748), and whom Elizabeth opposed but wished to placate. In 1744 Sophie came to Russia with her mother and there was instructed in Orthodoxy, eventually taking the name Catherine at conversion. Thus at the age of fifteen the future Catherine the Great took up her position at the Russian court as the wife of the heir to the throne. The young girl was lonely, and her mother’s intrigues only increased their isolation. The one bright spot for the princess was that she got along with the Empress well on a personal level." Bushkovitch, Paul. A Concise History of Russia (Cambridge Concise Histories) (p. 113). Cambridge University Press.

REQUIRED READING

RECOMMENDED READING

Robert Massie,

Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman,

Random House Trade Paperbacks,

ISBN 0345408772

All

Week 1: Tue., Oct. 11, 2022

Russia Before the Russians

Week 1

"Russian history begins with the polity that scholars have come to call Kiev Rus, the ancestor of modern Russia. Rus was the name that the inhabitants gave to themselves and their land, and Kiev was its capital. In modern terms, it embraced all of Belarus, the northern half of the Ukraine, and the center and northwest of European Russia. The peoples of these three modern states are the Eastern Slavs, who all speak closely related languages derived from the East Slavic language of Kiev Rus. In the west its neighbors were roughly the same as the neighbors of those three states today: Hungary, Poland, the Baltic peoples, and Finland. In the north Kiev Rus stretched toward the Arctic Ocean, with Slavic farmers only beginning to move into the far north. Beyond the Slavs to the east was Volga Bulgaria, a small Turkic Islamic state that came into being in about AD 950 where modern Tatarstan stands today. Beyond Volga Bulgaria were the Urals and Siberia, vast forests and plains inhabited by small tribes who lived by hunting and gathering food. The core of Kiev Rus was along the route that ran from northern Novgorod south to Kiev along the main rivers. There in the area of richest soil lay the capital, Kiev. Even farther to the south of Kiev began the steppe." Bushkovitch, Paul. A Concise History of Russia (Cambridge Concise Histories) (p. 1). Cambridge University Press.

REQUIRED READING

The book below is our year-long history book that we will all use. You will be very grateful as we proceed, to have this succinct, well-organized volume available. It is part of the Concise History series at Cambridge University Press. Please buy it using this link so that the Institute gets a little financial credit for the purchase.

Review

"For any student trying to get a grasp of the essentials of Russian history this book is the place to start. To cover everything from the origins of the Russian people to the collapse of the Soviet Union in one short book requires great skill, but Paul Bushkovitch is one of the leading experts on Russian history in the world and he manages this task with great insight and panache."

Dominic Lieven, Trinity College, Cambridge University

"This is a lively and readable account, covering more than a thousand years of Russian history in an authoritative narrative. The author deals perceptively not only with political developments, but also with those aspects of modern Russian culture and science that have had an international impact."

Maureen Perrie, University of Birmingham

"If you want to understand Russia, and the story of the Russians, you can do no better than Paul Bushkovitch’s A Concise History of Russia. Bushkovitch has performed a minor miracle: he’s told the remarkably complicated, convoluted, and controversial tale of Russian history simply, directly, and even-handedly. He doesn’t get mired in the details, lost in the twists and turns, or sidetracked by axe grinding. He tells you what happened and why, full stop. So if you want to know what happened and why in Russian history, you be advised to begin with Bushkovitch's masterful introduction."

Marshall Poe, University of Iowa

Week 2: Tue., Oct. 18, 2022

Kievan Rus

Week 2

Kievan Rus was a loose federation of East Slavic and Uralic peoples in Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century, under the reign of the Rurik dynasty, founded by the Varangian prince Rurik. The modern nations of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine all claim Kievan Rus as their cultural ancestors, with Belarus and Russia deriving their names from it. The Rurik dynasty would continue to rule parts of Rus' until the 16th century with the Tsardom of Russia. At its greatest extent, in the mid-11th century, it stretched from the White Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south and from the headwaters of the Vistula in the west to the Taman Peninsula in the east, uniting the majority of East Slavic tribes. According to Rus Primary Chronicle, the first ruler to start uniting East Slavic lands into what has become known as Kievan Rus was Prince Oleg (879–912). He extended his control from Novgorod south along the Dnieper river valley to protect trade from Khazar incursions from the east, and moved his capital to the more strategic Kiev.

Also, we should take note of the neighboring Bulgarians at the same period. Csar Simeon I the Great ruled over Bulgaria from 893 to 927, during the First Bulgarian Empire. Simeon's successful campaigns against the Byzantines, Magyars and Serbs led Bulgaria to its greatest territorial expansion ever, making it the most powerful state in contemporary Eastern and Southeast Europe. His reign was also a period of unmatched cultural prosperity and enlightenment later deemed the Golden Age of Bulgarian culture. During Simeon's rule, Bulgaria spread over a territory between the Aegean, the Adriatic and the Black Sea. The newly independent Bulgarian Orthodox Church became the first new patriarchate besides the Pentarchy, and Bulgarian Glagolitic and Cyrillic translations of Christian texts spread all over the Slavic world of the time. It was at the Preslav Literary School in the 890s that the Cyrillic alphabet was developed. Halfway through his reign, Simeon assumed the title of Emperor (Csar), having prior to that been styled Prince.

REQUIRED READING

Week 3: Tue., Oct. 25, 2022

Christians Come to Russia

Week 3

"The moment the first East Slavic state—the precursor of today’s Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus—began to coalesce was the same moment of its Christianization a thousand years ago. Therefore, Christianity has been central to Russian culture throughout its history."

ScotT Kenworthy, Understanding World Christianity: Russia 5 (p. 63). Fortress Press

The church tradition of Georgia and Ukraine regards Saint Andrew as the first preacher of Christianity in the territory of Georgia and Ukraine and as the founder of the Georgian and Ukraine church. This tradition was apparently derived from the Byzantine sources, particularly Nicetas of Paphlagonia (died c. 890) who asserts that "Andrew preached to the Iberians, Sauromatians, Taurians, and Scythians and to every region and city, on the Black Sea, both north and south." This version was adopted by the 10th–11th-century Georgian ecclesiastics and, refurbished with more details, was inserted in the Georgian Chronicles. The story of Saint Andrew's mission in the Georgian lands endowed the Georgian church with apostolic origin and served as a defence argument to George the Hagiorite against the encroachments from the Antiochian church authorities on the Georgian church. The Georgian Orthodox Church marks two feast days in honor of Saint Andrew, on 12 May and 13 December. The former date, dedicated to Saint Andrew's arrival in Georgia, is a public holiday in Georgia.

REQUIRED READING

RECOMMENDED READING

Scott Kenworthy,

Understanding World Christianity: Russia,

Fortress Press (January 19, 2021),

ISBN 1451472501

Editorial Reviews

"Written by two of the world's leading scholars of Russian Orthodoxy, this splendid volume fills a huge gap in the literature of World Christianity. Kenworthy and Agadjanian's skillful overview balances theological traditions and historical developments with nuanced treatment of contemporary issues. Accessible to broad audiences, and also useful for specialists, it introduces the rich devotional and institutional life of Russia's majority Christian tradition. I recommend it very highly." --Dana L. Robert, Truman Collins Professor of World Christianity and History of Mission, Boston University

"This powerful and engaging book provides clear-headed knowledge about Russian Orthodoxy, its faith and religious practice, its aspirations and fears. No one could read this book without gaining understanding and insight. A wonderful book! Essential reading!" --Archpriest Andrew Louth FBA, Professor Emeritus, University of Durham, UK

"In this luminously written study we have a most beautiful introduction to Russian Christianity that is at once masterly in its coverage and also deeply fascinating in its level of detail." --John A. McGuckin, Oxford University Faculty of Theology

"This excellent guide to Russian Orthodoxy is much needed, as the subject is poorly understood, even by many experts on Russia. Kenworthy sums up lucidly the serious research done by scholars in recent years, and displays the Orthodox Church in all its spiritual, theological, geographic and ethnic diversity." --Geoffrey Hosking, Emeritus Professor of Russian History, University College London

"This compact study of Christianity in Russia, by leading historian Scott Kenworthy and historical sociologist Alexander Agadjanian, provides a systematic and sophisticated account of Christianity in Russia from its medieval origins to the present day. It is a state-of-the-art piece of scholarship, reflecting the massive research in Russia and abroad since the collapse of the Soviet Union moved the study of religion to the front burner. Specialists and non-specialists will profit from a close reading of this important volume." --Gregory Freeze, Brandeis University

Week 4: Tue., Nov. 1, 2022

Mongolians

Week4

"After the gradual disintegration of Kiev Rus, the regional powers that supplanted it began to grow apart. In these centuries the territories of Novgorod and the old northeast began to form a distinct language and culture that we can call Russian. Though the older term Rus persisted until replaced by Russia (Rossiia) in the fifteenth century, for this period we may begin to call the area Russia and the people Russian. In these centuries, Russia, like the other territories of Kiev Rus that would fall to Lithuania, experienced a cataclysm in the form of the Mongol invasion, one that shaped its history for the next three centuries. The Mongol Empire was the last and largest of the nomadic empires formed on the Eurasian steppe. It was largely the work of Temuchin, a Mongolian chieftain who united the Mongolian tribes in 1206 and took the name of Genghis Khan. In his mind, the Eternal Blue Heaven had granted him rule over all people who lived in felt tents, and he was thus the legitimate ruler of all inner Asian nomads. The steppe was not enough. In 1211 Genghis Khan moved south over the Great Wall and overran northern China. His armies then swept west, and by his death in 1227, they had added all of Inner and Central Asia to their domains." Bushkovitch, Paul. A Concise History of Russia (Cambridge Concise Histories) (p. 19). Cambridge University Press.

REQUIRED READING

Week 5: Tue., Nov. 8, 2022

The Birth of Russia

Week 5

"At the end of the fifteenth century, Russia came into being as a state – no longer just a group of related principalities. Precisely at this time in written usage the modern term Rossia (a literary expression borrowed from Greek) began to edge out the traditional and vernacular Rus. If we must choose a moment for the birth of Russia out of the Moscow principality, it is the final annexation of Novgorod by Grand Prince Ivan III (1462–1505) of Moscow in 1478. By this act, Ivan united the two principal political and ecclesiastical centers of medieval Russia under one ruler, and in the next generation he and his son Vasilii III (1505–1533) added the remaining territories. In the west and north, the boundaries they established are roughly those of Russia today, while in the south and east the frontier for most of its length remained the ecological boundary between forest and steppe. In spite of later expansion, this territory formed the core of Russia until the middle of the eighteenth century, and it contained most of the population and the centers of state and church. The Russians were still a people scattered along the rivers between great forests." Bushkovitch, Paul. A Concise History of Russia (Cambridge Concise Histories) (p. 37). Cambridge University Press.

REQUIRED READING

Week 6: Tue., Nov. 15, 2022

Boris Godunov

Week 6

"On Ivan’s death the country was slowly recovering from the disasters of the last twenty-five years of his reign. He had two surviving sons, the eldest Fyodor from Anastasiia and Dmitrii (born 1582) from his fourth wife, Mariia Nagaia. Fyodor, who appears to have been limited in both abilities and health, was married to Irina Godunov, the sister of Boris Godunov, a boyar who had risen from modest origins in the landholding class through the Oprichnina. With the accession of his brother-in-law to the throne, Boris was now in a position to become the dominant personality around the tsar. First, however, he had to get rid of powerful boyar rivals who saw their chance to restore their power at the court. Indeed at the beginning of Fyodor’s reign virtually every boyar clan that had suffered under Ivan returned to the duma if they had not already done so. Boris lost no time in marginalizing them one by one and forcing some into exile. His second problem was the presence of the tsarevich Dmitrii, for Fyodor and Irina had only a daughter who died in infancy." Bushkovitch, Paul. A Concise History of Russia (Cambridge Concise Histories) (pp. 53-54). Cambridge University Press.

REQUIRED READING

THANKSGIVING NEXT WEEK NO CLASS

Week 7: Tue., Nov. 29, 2022

Tsar Michael

Week 7

Michael I (Mikhaíl Fyodorovich Románov) (1596 – 1645) became the first Russian Tsar of the House of Romanov after the zemskiy sobor of 1613 elected him to rule the Czardom of Russia. He was the son of Feodor Nikitich Romanov (later known as Patriarch Filaret) and of Xenia (later known as "the great nun" Martha). He was also a first cousin once removed of the last Rurikid Czar Feodor I through his great-aunt Anastasia Romanovna, who was the mother of Feodor I, and through marriage, a great-nephew in-law with Czar Ivan IV of Russia. His accession marked the end of the "Time of Troubles". During his reign, Russia conquered most of Siberia, largely with the help of the Cossacks and the Stroganov family. Russia had extended to the Pacific Ocean by the end of Michael's reign. Michael's grandfather, Nikita, was brother to the first Russian Tsaritsa Anastasia and a central advisor to Ivan the Terrible. As a young boy, Michael and his mother had been exiled to Beloozero in 1600. This was a result of the recently elected Tsar Boris Godunov, in 1598, falsely accusing his father, Feodor, of treason. This may have been partly because Feodor had married Ksenia Shestova against Boris' wishes. Michael was unanimously elected Tsar of Russia by a national assembly on 21 February 1613, but the delegates of the council did not discover the young Tsar and his mother at the Ipatiev Monastery near Kostroma until 24 March. He had been chosen after several other options had been removed, including royalty of Poland and Sweden. Initially, Martha protested, believing and stating that her son was too young and tender for so difficult an office, and in such a troublesome time. (Wikipedia)

Michael I (Mikhaíl Fyodorovich Románov) (1596 – 1645) became the first Russian Tsar of the House of Romanov after the zemskiy sobor of 1613 elected him to rule the Czardom of Russia. He was the son of Feodor Nikitich Romanov (later known as Patriarch Filaret) and of Xenia (later known as "the great nun" Martha). He was also a first cousin once removed of the last Rurikid Czar Feodor I through his great-aunt Anastasia Romanovna, who was the mother of Feodor I, and through marriage, a great-nephew in-law with Czar Ivan IV of Russia. His accession marked the end of the "Time of Troubles". During his reign, Russia conquered most of Siberia, largely with the help of the Cossacks and the Stroganov family. Russia had extended to the Pacific Ocean by the end of Michael's reign. Michael's grandfather, Nikita, was brother to the first Russian Tsaritsa Anastasia and a central advisor to Ivan the Terrible. As a young boy, Michael and his mother had been exiled to Beloozero in 1600. This was a result of the recently elected Tsar Boris Godunov, in 1598, falsely accusing his father, Feodor, of treason. This may have been partly because Feodor had married Ksenia Shestova against Boris' wishes. Michael was unanimously elected Tsar of Russia by a national assembly on 21 February 1613, but the delegates of the council did not discover the young Tsar and his mother at the Ipatiev Monastery near Kostroma until 24 March. He had been chosen after several other options had been removed, including royalty of Poland and Sweden. Initially, Martha protested, believing and stating that her son was too young and tender for so difficult an office, and in such a troublesome time. (Wikipedia)

A NOTE ON CZAR VERSUS TSAR:

Tsar also spelled czar, tzar, or csar, is a title used to designate East and South Slavic monarchs or supreme rulers of Eastern Europe, originally the Bulgarian monarchs from 10th century onwards, much later a title for two rulers of the Serbian Empire, and from 1547 the supreme ruler of the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire. In this last capacity it lends its name to a system of government, tsarist autocracy or tsarism. The term is derived from the Latin word caesar, which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the term—a ruler with the same rank as a Roman emperor, holding it by the approval of another emperor or a supreme ecclesiastical official (the Pope or the Ecumenical Patriarch)—but was usually considered by western Europeans to be equivalent to king, or to be somewhat in-between a royal and imperial rank.

"Tsar" and its variants were the official titles of the following states:

Bulgarian Empire (First Bulgarian Empire in 919–1018, Second Bulgarian Empire in 1185–1396)

Serbian Empire, in 1346–1371

Tsardom of Russia, in 1547–1721 (replaced in 1721 by imperator in Russian Empire, but still remaining in use, also officially in relation to several regions until 1917)

The first ruler to adopt the title tsar was Simeon I of Bulgaria.

REQUIRED READING

Week 8: Tue., Dec. 6, 2022

Peter the Great

Week 8

"The reign of Peter the Great saw the greatest transformation in Russia until the revolution of 1917. Unlike the Soviet revolution, Peter’s transformation of Russia had little impact on the social order, for serfdom remained and the nobility remained their masters. What Peter changed was the structure and form of the state, turning the traditional Russian tsardom into a variant of European monarchy. At the same time he profoundly transformed Russian culture, a contribution that along with his new capital of St. Petersburg has lasted to the present day." Bushkovitch, Paul. A Concise History of Russia (Cambridge Concise Histories) (p. 79). Cambridge University Press.

REQUIRED READING

RECOMMENDED READING

Week 9: Tue., Dec. 13, 2022

Two Empresses

Week 9

"With the restoration of autocracy, Duchess Anna of Courland came to the throne as Empress of Russia, and after a time she sent the leaders of the Golitsyn and Dolgorukii clans into exile. The ten years of Anna’s reign in the memory of the Russian nobility was a dark period of rule by Anna’s German favorites – particularly her chamberlain – Ernst-Johann Bühren (Biron to the Russians), who was allegedly all-powerful and indifferent to Russian interests. That memory was a considerable exaggeration. After a brief interlude, Empress Elizabeth, Peter the Great’s daughter and a capable and strong monarch succeeded her (1741–1761). Underneath all the drama at court, Russia’s new culture took shape, and Russia entered the age of the Enlightenment. In these decades we can also get a glimpse of Russian society that goes beyond descriptions of legal status into the web of human relations. Politically Anna’s court was not a terribly pleasant place, though the story of “German domination” is largely a legend. Anna was personally close to Biron, who had served her well in Courland, where she had lived since the death of her husband the duke in 1711. She entrusted foreign policy to Count Andrei Ostermann and the army to Count Burkhard Christian Münnich, but the three were in no sense a clique. Indeed, they hated one another and made alliances with the more numerous Russian grandees in the court and in the government. The truth was that Anna relied on them and a few others and she did not consult with the elite as a whole. The Senate languished. Not surprisingly, Anna was terrified that there would be plots against her in favor of Elizabeth, Peter’s eldest surviving daughter, or other candidates for the throne" Bushkovitch, Paul. A Concise History of Russia (Cambridge Concise Histories) (pp. 101-102). Cambridge University Press.

You can see in the map below, the the Duchy of Courland would be in Lithuania today. But in the 18th century, its position on the border of Prussia, Lithuania, and Russia made it a valuable prize.

REQUIRED READING

RECOMMENDED READING

This book about Frederick the Great helps the reader understand much of Russian history since Frederick is in the background of all the maneuvering inside the Russian court.

Week 10: Tue., Dec. 20, 2022

Young Catherine

Week 10

Empress Elizabeth makes plans for a successor and finds this young man a wife from Germany: this is the future Catherine the Great called Sophie when she first came to Russia with her mother in 1744.

"Empress Elizabeth, like her predecessor Anna, had to provide for a succession to her throne, as she had no children of her own. She chose her nephew, Karl Peter Ulrich, the Duke of Holstein-Gottorp and the son of her older sister Anna Petrovna, who had married the then Duke in 1725. Elizabeth’s idea was to keep the succession in her family, not in the family of Empress Anna. The Holstein connection also had diplomatic advantages in relation to Sweden and the German states, especially Prussia. Elizabeth brought the boy to Russia in 1742 with a large suite of Holsteiners and he converted to Orthodoxy with the name Peter in honor of his grandfather, Peter the Great. The young Peter was not a particularly promising boy, and Elizabeth decided that he needed a wife. She chose Sophie, the daughter of the Duke of Anhalt-Zerbst – Anhalt-Zerbst being a small German principality in the Prussian orbit. Sophie’s mother was also from the Holstein family, so that Sophie and Peter were cousins and were both related to the then King of Sweden. The family also had the support of Frederick the Great of Prussia, victorious in war with Austria (1740–1748), and whom Elizabeth opposed but wished to placate. In 1744 Sophie came to Russia with her mother and there was instructed in Orthodoxy, eventually taking the name Catherine at conversion. Thus at the age of fifteen the future Catherine the Great took up her position at the Russian court as the wife of the heir to the throne. The young girl was lonely, and her mother’s intrigues only increased their isolation. The one bright spot for the princess was that she got along with the Empress well on a personal level." Bushkovitch, Paul. A Concise History of Russia (Cambridge Concise Histories) (p. 113). Cambridge University Press.

REQUIRED READING

RECOMMENDED READING

Robert Massie,

Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman,

Random House Trade Paperbacks,

ISBN 0345408772