Week 1

Week 1: Tuesday, October 5, 2021

Germany Before the Germans

WEEK 1

It was Julius Caesar who named the area east of the Rhine as "Germania." Cologne was already a very important Roman city on the Rhine, but only on the west side of the Rhine. The whole vast area east of the Rhine was still unconquered territory in Caesar's day. The victory of the Germanic tribes in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (AD 9) prevented annexation by the Roman Empire, although the Roman provinces of Germania Superior and Germania Inferior were established along the west side of the Rhine. Following the Fall of the Western Roman Empire after 400 AD, the Franks conquered the other West Germanic tribes which led to the new early Medieval empire, the Kingdom of the Franks. The Kingdom of the Franks included much of France and western Germany. Out of this vast territory would emerge the Carolingian empire (with both French and German territories) in the 700s and the Holy Roman Empire in the 900s.

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

TIMELINE OF GERMAN HISTORY:

2

Week 2: Tuesday, October 12, 2021

Germanicus

WEEK 2

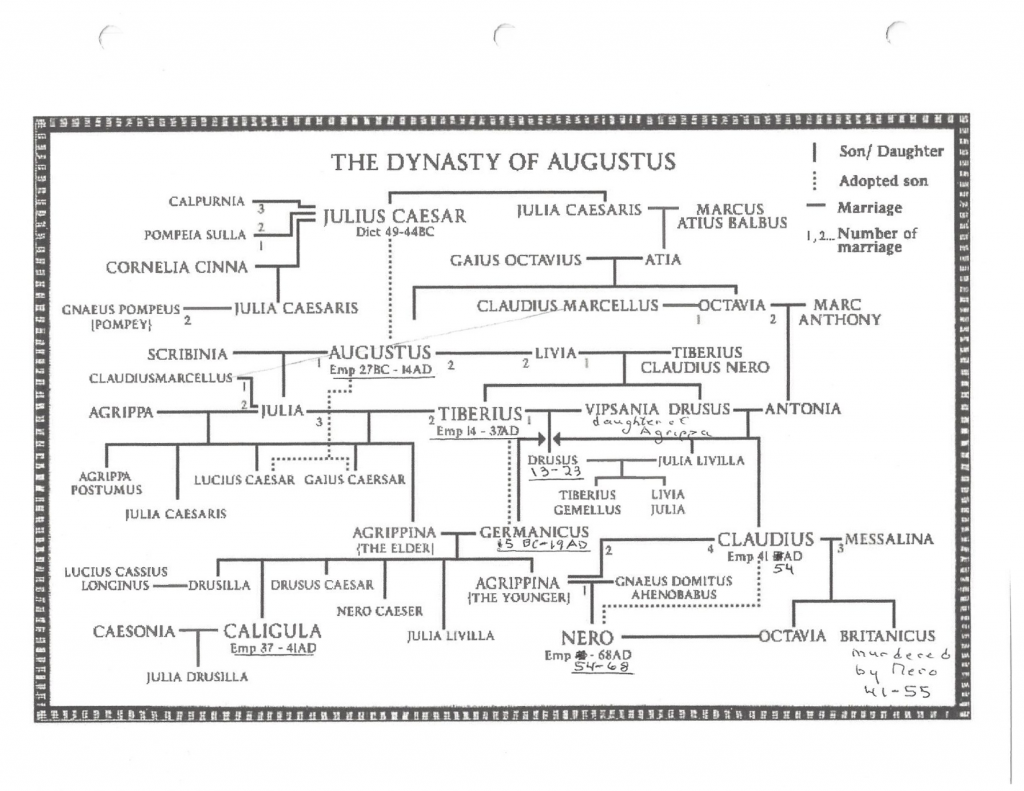

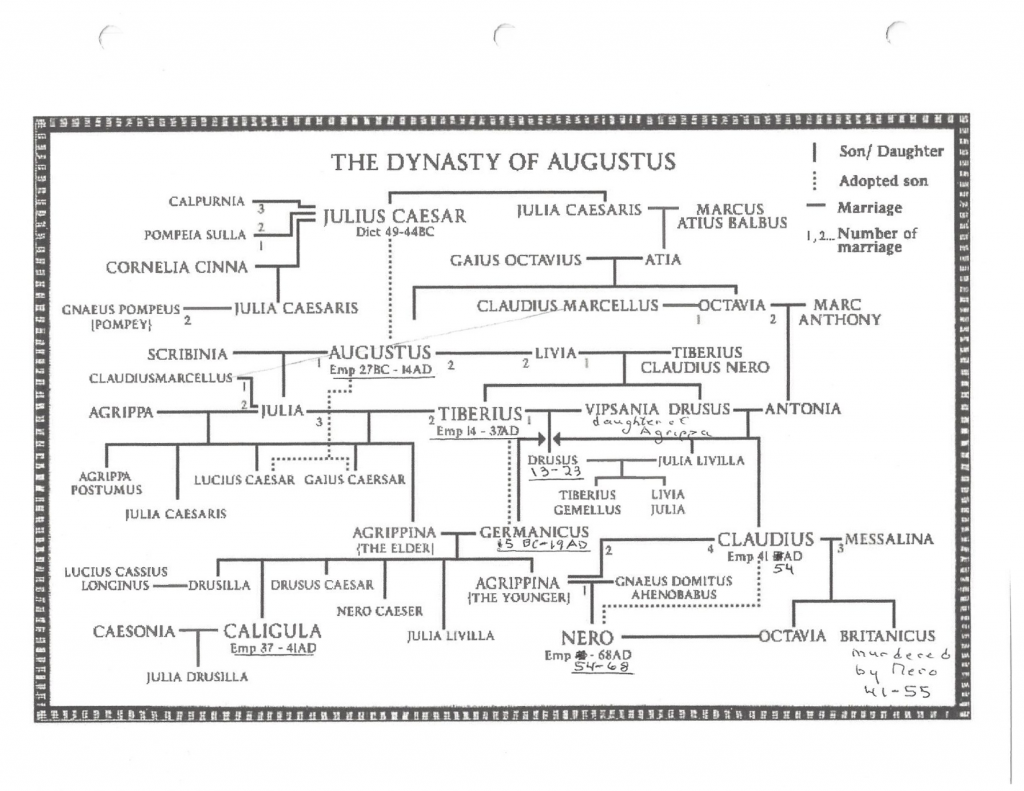

The most dramatic and memorable chapter in the relationship between Rome and Germany took place in the first century BC-AD during the lifetime of the Roma general Germanicus. The name was a nickname given to him by his troops and the Roman public who adored him. Germanicus' own campaigns in Germany made him famous after avenging the defeat at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (9 BC) and retrieving two of the three legionary eagles that had been lost during the battle. Beloved by the people, he was widely considered to be the perfect Roman long after his death. The Roman people for centuries would consider him as Rome's Alexander the Great due to the nature of his death at a young age, his virtuous character, his dashing physique and his military renown. His place in the imperial family is visible in the chart below. He was the son of Drusus and Antonia. Antonia was the daughter of Mark Anthony and Augustus' sister Octavia. Drusus and his brother Claudius were royalty. And so was the brilliant young man "Germanicus."

The most dramatic and memorable chapter in the relationship between Rome and Germany took place in the first century BC-AD during the lifetime of the Roma general Germanicus. The name was a nickname given to him by his troops and the Roman public who adored him. Germanicus' own campaigns in Germany made him famous after avenging the defeat at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (9 BC) and retrieving two of the three legionary eagles that had been lost during the battle. Beloved by the people, he was widely considered to be the perfect Roman long after his death. The Roman people for centuries would consider him as Rome's Alexander the Great due to the nature of his death at a young age, his virtuous character, his dashing physique and his military renown. His place in the imperial family is visible in the chart below. He was the son of Drusus and Antonia. Antonia was the daughter of Mark Anthony and Augustus' sister Octavia. Drusus and his brother Claudius were royalty. And so was the brilliant young man "Germanicus."

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

3

Week 3: Tuesday, October 19, 2021

The Franks

WEEK 3

The Franks (Latin: Franci) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire. Later the term was associated with Romanized Germanic dynasties within the collapsing Western Roman Empire, who eventually commanded the whole region between the rivers Loire and Rhine. They imposed power over many other post-Roman kingdoms and Germanic peoples. Still later, Frankish rulers were given recognition by the Catholic Church as successors to the old rulers of the Western Roman Empire. Although the Frankish name does not appear until the 3rd century, at least some of the original Frankish tribes had long been known to the Romans under their own names, both as allies providing soldiers, and as enemies. The new name first appears when the Romans and their allies were losing control of the Rhine region. The Franks were first reported as working together to raid Roman territory. However, from the beginning the Franks also suffered attacks upon them from outside their frontier area, by the Saxons, for example, and as frontier tribes they desired to move into Roman territory, with which they had had centuries of close contact.

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

4

Week 4: Tuesday, October 26, 2021

Saint Boniface and German Christians

WEEK 4

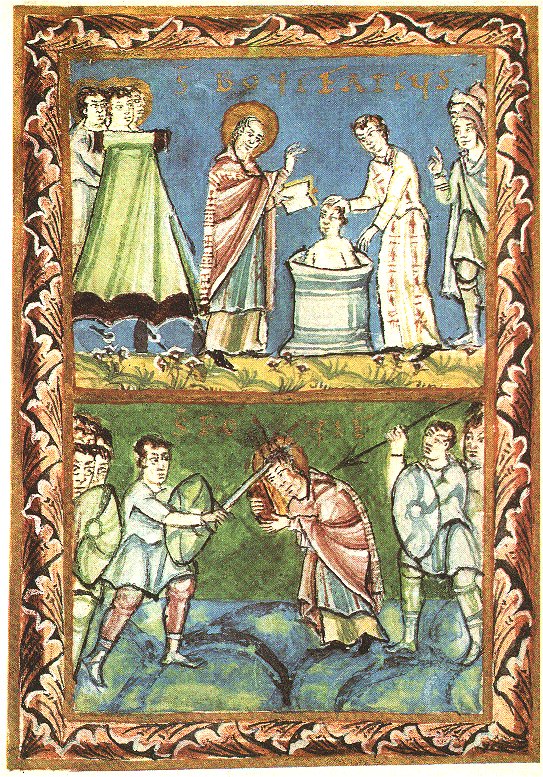

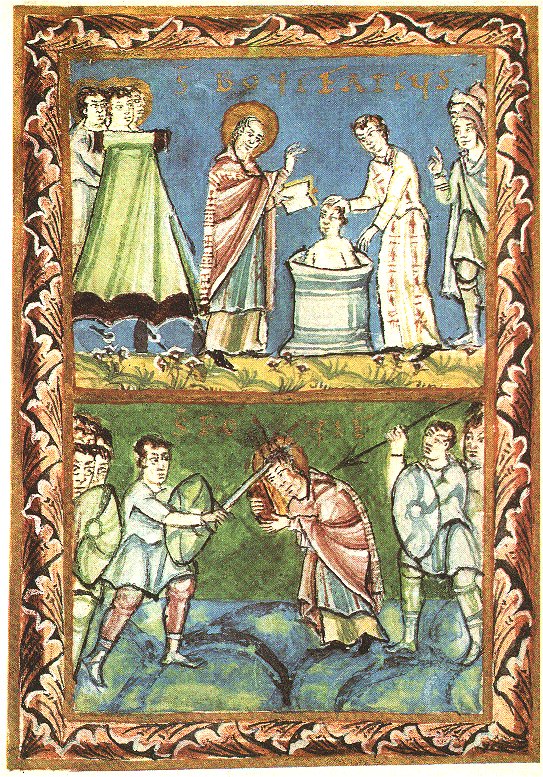

Saint Boniface, "The Apostle to the Germans" was not a German. He came from a little Devon town in southern England. He studied at a monastery close by and in the early 700s went to the Continent to share the Christian teaching with the still unconverted Franks and Belgians. He preached in the northern areas of present day Belgium, the Netherlands and northern Germany with extraordinary success and is still seen as the man who turned Germany to Christianity. He was martyred in 754 in Frisia by bandits who expected to find riches among the travelers possessions. The body of Boniface was taken to the church in Fulda where he remains to this day. Boniface was important in three ways for Germany. First, he organized the growing German church. Through his efforts to reorganize and regulate the church of the Franks, he helped shape the Latin Church in Europe, and many of the dioceses he proposed remain today. He also helped shape the doctrine and practices of the German church to bring it into conformity with the teaching of the Vatican. Most important of all, he was the creator of the alliance between the Papacy and the Carolingian dynasty. This alliance was going to bring into existence the Holy Roman Empire, one of the dominant institutions of the Middle Ages. See below, a Medieval Illuminated book illustration that shows Boniface baptizing and Boniface being murdered.

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

5

Week 5: Tuesday, November 2, 2021

The Carolingians

WEEK 5

The Carolingian dynasty was a Frankish noble family founded by Charles Martel with origins in the Arnulfing and Pippinid clans of the 7th century AD. The dynasty consolidated its power within the Frankish political class in Tours, the capital of the Kingdom, during the 700s. In 751 the older Frankish Merovingian dynasty which had ruled the Germanic Franks for several hundred years, was overthrown with the consent of the Papacy, and the Frankish aristocracy. And Pepin the Short, son of Charles Martel, was crowned King of the Franks. The Carolingian dynasty reached its peak in 800 with the crowning of Pepin's son, Charles the Big, Charlemagne, as the first "Emperor of Romans" in the West in over three centuries. He was crowned in Rome by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day, 800. His death in 814 began an extended period of fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire and decline that would eventually lead to the evolution of a new kingdom in the West called the Kingdom of France, and another new institution in German lands called The Holy Roman Empire, which as Voltaire remarked: "was neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire." You might remember that wonderful witty line as you plunge into the complexity of the Holy Roman Empire, since Voltaire was both very funny and very correct. The HRE (a nice abbreviation) really was a German institution driven by German medieval politics for about 700 years.

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

Einhard,

The Life of Charlemagne,

Ann Arbor Paperbacks,

ISBN 047206035X

ABOUT THIS BOOK:

Vita Karoli Magni (Life of Charles the Great) is a biography of Charlemagne, King of the Franks and Holy Roman Emperor, written by Einhard. Historians have traditionally described the work as the first example of a biography of a European king. The author endeavored to imitate the style of that of the ancient Roman biographer Suetonius, most famous for his work the Twelve Caesars. Einhard's biography is especially modeled after the biography of Emperor Augustus, the first emperor of the Roman Empire. The date of the work is uncertain and a number of theories have been put forward. The inclusion of Charlemagne's will at the end of the work makes it fairly clear that it was written after his death in 814. The first reference to the work, however, comes in a letter to Einhard from Lupus of Ferrieres which is dated to the mid-ninth century. Dates have been suggested ranging from about 817 to 833, usually based on interpretations of the text in the political context of the first years of the reign of Louis the Pious and Louis' attitude to his father. Einhard's book is about intimate glimpses of Charlemagne's personal habits and tastes. He occupied favoured position at Charlemagne's court so he had inside information. Einhard received advanced schooling at the monastery of Fulda sometime after 779. Here he was an exceptional student and was quite knowledgeable. The word was sent to Charlemagne of Einhard's expertise. He was then sent to Charlemagne’s Palace School at Aachen in 791. Einhard then received employment at Charlemagne's Frankish court about 796. He remained at this position for twenty some years. Einhard's book was expressly intended to convey his appreciation for advanced education. He wrote his biography after he had left Aachen and was living in Seligenstadt. Einhard's position while with Charlemagne was that of a modern day minister of public works, so he had intimate knowledge of his court. Einhard was also given the responsibility of many of Charlemagne's abbeys.

This is the source of all our knowledge of Charlemagne written by someone who knew him. It is a small book, easy to read, and a small gem. Go get it.

RECOMMENDED READING

If you would like the very best biography of Charlemagne, here it is, new and from our own University of California Press. It is in the Institute library. We are open all day all week if you was to borrow this or any other book.

Janet Nelson,

King and Emperor: A New Life of Charlemagne,

University of California Press; First Edition (September 17, 2019),

ISBN 0520314204

Editorial Reviews

Review

"A deeply learned and humane portrait . . . Nelson’s King and Emperor brings alive the age of Charlemagne, the ruler usually associated with the first effort after the fall of Rome to unite Europe under a single rule. This 'new life' is a bold book. . . . Each chapter is a masterclass in tracing specific bodies of evidence back to the persons or incidents from which they arose. . . . King and Emperor is a masterpiece of historical writing and a robust step toward filling the gap in our historical imagination left by the passing of Rome."

, New York Review of Books

"Janet Nelson assembles an astonishingly rich picture from the most unrewarding of texts. The way she puzzles out probable facts and motivations, based on a complete reading of the existing texts, is a joy to witness. She draws on and shows off the clever work of earlier historians, while giving short shrift to their more biased assumptions. The narrative voice emerges as that of a patient, inquisitive, incisive and helpful master detective, with funny asides, a beautiful style and sensible politics."

, Times Literary Supplement

""There have been countless studies of Charlemagne in many languages...but few have been as ambitiously biographical as Nelson’s. Historians of early medieval Europe are trained to interpret scattered clues and fragments, however, and Nelson is one of the very best."

, London Review of Books

"King and Emperor takes on the compelling suspense of good detective work as well as good history. . . . Janet L. Nelson comes as close as one can to approaching this extraordinary man."

, Wall Street Journal

6

Week 6: Tuesday, November 9, 2021

The Ottonians

WEEK 6

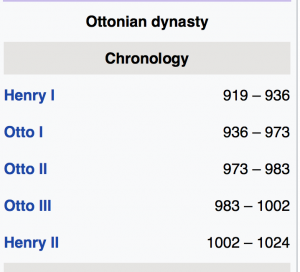

In the period after the death of Charlemagne in 814, the successive generations of his sons and grandsons were unable to hold the empire together. Similar territories within the Roman Empire had required hundreds of years to become well integrated into an international empire. And the Carolingians had tried to do it all in just three. In the next 200 years, the slow disintegration produced a myriad of small states, dukedoms, bishoprics etc. that developed their own histories and institutions. For 200 years there wsa no unity and no one dominant German family. Then in the late 900s, the Ottonians emerged. The Ottonian dynasty (German: Ottonen) was a Saxon dynasty of German monarchs(919–1024), named after three of its kings and Holy Roman Emperors named Otto, especially its first Emperor Otto I. It is also known as the Saxon dynasty after the family's origin in the German duchy of Saxony. When this very strong new dynasty of the Ottonians emerged around the late 900s (Otto I, II, III) the choice of the king/emperor had already evolved into an election within which the seven most powerful states chose the next emperor. Therefore, the complex electoral process of choosing the new emperor emerged and remained right to the end of the Empire when Napoleon essentially ended it in 1806.

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

7

Week 7: Tuesday, November 16, 2021

Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II

WEEK 7

Frederick II (26 December 1194 – 13 December 1250) was King of Sicily from 1198, King of Germany from 1212, King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor from 1220 and King of Jerusalem from 1225. He was the son of emperor Henry VI of the Hohenstaufen dynasty and of Constance, heiress to the Norman kings of Sicily. His political and cultural ambitions were enormous as he ruled a vast area, beginning with Sicily and stretching through Italy all the way north to Germany. As the Crusades progressed, he acquired control of Jerusalem and styled himself its king. However, the Papacy became his enemy, and it eventually prevailed. Viewing himself as a direct successor to the Roman emperors of antiquity, he was Emperor of the Romans from his papal coronation in 1220 until his death; he was also a claimant to the title of King of the Romans from 1212 and unopposed holder of that monarchy from 1215. As such, he was King of Germany, of Italy, and of Burgundy. At the age of three, he was crowned King of Sicily as a co-ruler with his mother, Constance of Hauteville, the daughter of Roger II of Sicily. His other royal title was King of Jerusalem by virtue of marriage and his connection with the Sixth Crusade. Frequently at war with the papacy, which was hemmed in between Frederick's lands in northern Italy and his Kingdom of Sicily (the Regno) to the south, he was excommunicated three times and often vilified in pro-papal chronicles of the time and after. Pope Gregory IX went so far as to call him an Antichrist. Speaking six languages (Latin, Sicilian, Middle High German, Langues d'oïl, Greek and Arabic, Frederick was an avid patron of science and the arts. He played a major role in promoting literature through the Sicilian School of poetry. His Sicilian royal court in Palermo, beginning around 1220, saw the first use of a literary form of an Italo-Romance language, Sicilian. The poetry that emanated from the school had a significant influence on literature and on what was to become the modern Italian language. He was also the first king to formally outlaw trial by ordeal, which had come to be viewed as superstitious. After his death his line did not survive, and the House of Hohenstaufen came to an end. Furthermore, the Holy Roman Empire entered a long period of decline during the Great Interregnum from which it did not completely recover until the reign of Charles V, 250 years later. (Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

NEXT WEEK THANKSGIVING BREAK

NO CLASSES ALL WEEK

8

Week 8: Tuesday, November 30, 2021

Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII

WEEK 8

Henry VII (German: Heinrich; c. 1278–August 24, 1313) was the King of Germany(or Rex Romanorum) from 1308 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1312. He was the first emperor of the House of Luxembourg. During his brief career he reinvigorated the imperial cause in Italy, which was racked with the partisan struggles between the divided Guelf and Ghibelline factions, and inspired the praise of Dino Compagni and Dante Alighieri. He was the first emperor since the death of Frederick II in 1250, ending the Great Interregnum of the Holy Roman Empire; however, his premature death threatened to undo his life's work. His son, John of Bohemia, failed to be elected as his successor, and there was briefly another anti-king, Frederick the Fair contesting the rule of Louis IV. (Wikipedia)

Henry met Dante in Pisa in 1311. Dante's alto Arrigo

Henry is the famous alto Arrigo in Dante's Paradiso, in which the poet is shown the seat of honor that awaits Henry in Heaven. Henry in Paradiso xxx.137f is "He who came to reform Italy before she was ready for it". Dante also alludes to him numerous times in Purgatorio as the savior who will bring imperial rule back to Italy, and end the inappropriate temporal control of the Church. Henry VII's success in Italy was not lasting, however, and after his death the anti-imperial forces regained control.

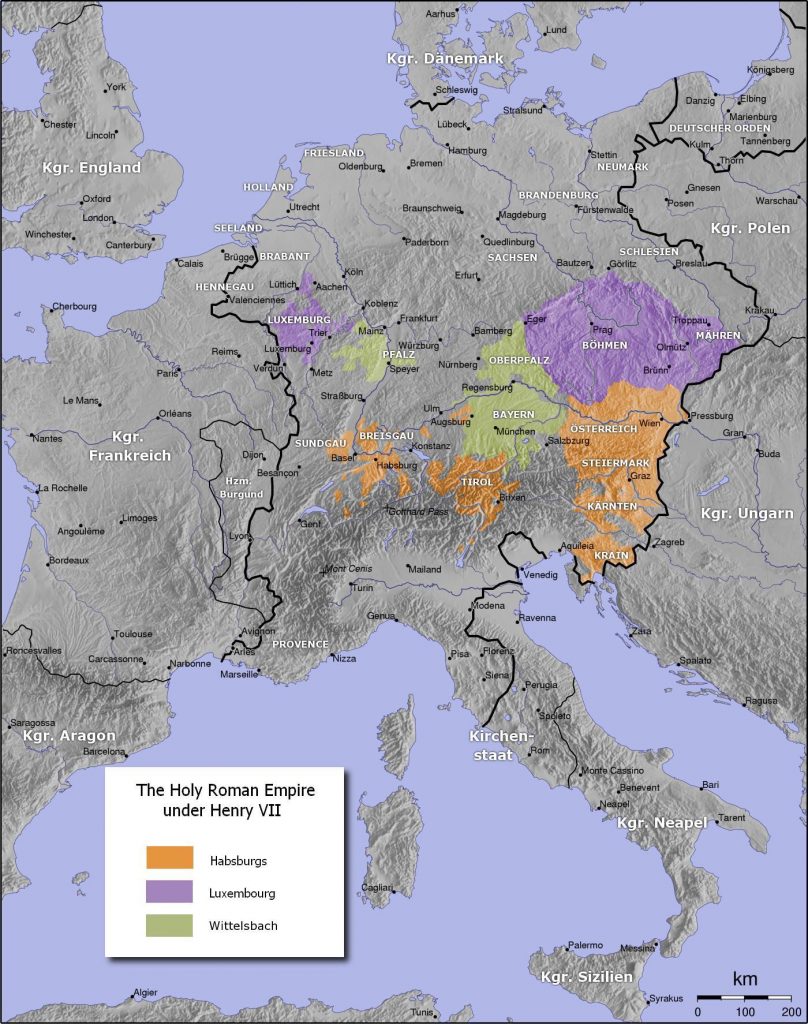

The map below shows you the lands held by Henry VII of Luxembourg. As you can see, his family holdings were very sparse within German territories. He added Bohemia through marriage. He hoped to expand his power, by using his role as Holy Roman Emperor to go into Italy and grow his power by adding Italian cities to his empire. This brought him face to face with an implacable foe: Florence.

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

9

Week 9: Tuesday, December 7, 2021

Germany and the Black Death

WEEK 9

The Black Death hit all European countries in 1348. Italy was first, with sailors arriving in Sicily early in the year carrying the plague. Then it moved to the mainland and then it moved north and over the Alps to Germany and the rest of northern Europe. The experience of the plague in Germany was unique. In Germany, especially in the Rhineland, hysteria about the plague manifested itself in a unique outbreak of anti-Semitism. In many ways this explosion of hatred of the Jews would not be repeated with this degree of intensity until the 20th century. From Wikipedia: "Renewed religious fervor and fanaticism bloomed in the wake of the Black Death. Some Europeans targeted "various groups such as Jews, friars, foreigners, beggars, pilgrims", lepers, and Romani, blaming them for the crisis. Lepers, and others with skin diseases such as acne or psoriasis, were killed throughout Europe. Because 14th-century healers and governments were at a loss to explain or stop the disease, Europeans turned to astrological forces, earthquakes, and the poisoning of wells by Jews as possible reasons for outbreaks. Many believed the epidemic was a punishment by God for their sins, and could be relieved by winning God's forgiveness. There were many attacks against Jewish communities. In the Strasbourg massacre of February 1349, about 2,000 Jews were murdered. In August 1349, the Jewish communities in Mainz and Cologne were annihilated. By 1351, 60 major and 150 smaller Jewish communities had been destroyed. During this period many Jews relocated to Poland, where they received a warm welcome from King Casimir the Great."

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

RECOMMENDED READING

John Kelly,

The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death,

Harper Pennial paperback, 2005,

ISBN 0060006935

REVIEW:

Amazon.com Review. A book chronicling one of the worst human disasters in recorded history really has no business being entertaining. But John Kelly's The Great Mortality is a page-turner despite its grim subject matter and graphic detail. Credit Kelly's animated prose and uncanny ability to drop his reader smack in the middle of the 14th century, as a heretofore unknown menace stalks Eurasia from "from the China Sea to the sleepy fishing villages of coastal Portugal [producing] suffering and death on a scale that, even after two world wars and twenty-seven million AIDS deaths worldwide, remains astonishing." Take Kelly's vivid description of London in the fall of 1348: "A nighttime walk across Medieval London would probably take only twenty minutes or so, but traversing the daytime city was a different matter.... Imagine a shopping mall where everyone shouts, no one washes, front teeth are uncommon and the shopping music is provided by the slaughterhouse up the road." Yikes, and that's before just about everything with a pulse starts dying and piling up in the streets, reducing the population of Europe by anywhere from a third to 60 percent in a few short years. In addition to taking readers on a walking tour through plague-ravaged Europe, Kelly heaps on the ancillary information and every last bit of it is captivating. We get a thorough breakdown of the three types of plagues that prey on humans; a detailed account of how the plague traveled from nation to nation (initially by boat via flea-infested rats); how floods (and the appalling hygiene of medieval people) made Europe so susceptible to the disease; how the plague triggered a new social hierarchy favoring women and the proletariat but also sparked vicious anti-Semitism; and especially, how the plague forever changed the way people viewed the church. Engrossing, accessible, and brimming with first-hand accounts drawn from the Middle Ages, The Great Mortality illuminates and inspires. History just doesn't get better than that. --Kim Hughes

10

Week 10: Tuesday, December 14, 2021

The Council of Constance

WEEK 10

The Council of Constance took place in the lovely lakeside city of Constance in the Cathedral of Constance. The international church council was the most important church council since the Council of Nicaea in 325 presided over by Emperor Constantine. The issue at Constance was the unity of the Church. The Roman Catholic Church was in tatters by 1400. During the 14th century, the church had found itself with two popes and then later with three. Two popes is one too many popes. The whole church knew by the late 1390s that somehow the Roman Christian church had to find a way back to unity. Thus was called a church council in Constance. Constance was a choice that attempted to satisfy both Northern European countries as well as the very important Italians. It was really "German" in a sense with German language population and a location on the edge of Germanic territories; it was French in the sense that much of the Swiss territories spoke French; and it was Italian with close ties to all the northern Italian Lake District cities and city states. The council's main purpose was to end the Papal schism which had resulted from the confusion following the Avignon Papacy. Pope Gregory XI's return to Rome in 1377, followed by his death (in 1378) and the controversial election of his successor, Pope Urban VI, resulted in the defection of a number of cardinals and the election of a rival pope based at Avignon in 1378. After thirty years of schism, the rival courts convened the Council of Pisa seeking to resolve the situation by deposing the two claimant popes and electing a new one. The council claimed that in such a situation, a council of bishops had greater authority than just one bishop, even if he were the bishop of Rome. Though the elected Antipope Alexander V and his successor, Antipope John XXIII (not to be confused with the 20th-century Pope John XXIII), gained widespread support, especially at the cost of the Avignon antipope, the schism remained, now involving not two but three claimants: Gregory XII at Rome, Benedict XIII at Avignon, and John XXIII. Therefore, many voices, including Sigismund, King of the Romans and of Hungary (and later Holy Roman Emperor), pressed for another council to resolve the issue. That council was called by John XXIII and was held from 16 November 1414 to 22 April 1418 in Constance, Germany

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

All

Week 1: Tue., Oct. 5, 2021

Germany Before the Germans

WEEK 1

It was Julius Caesar who named the area east of the Rhine as "Germania." Cologne was already a very important Roman city on the Rhine, but only on the west side of the Rhine. The whole vast area east of the Rhine was still unconquered territory in Caesar's day. The victory of the Germanic tribes in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (AD 9) prevented annexation by the Roman Empire, although the Roman provinces of Germania Superior and Germania Inferior were established along the west side of the Rhine. Following the Fall of the Western Roman Empire after 400 AD, the Franks conquered the other West Germanic tribes which led to the new early Medieval empire, the Kingdom of the Franks. The Kingdom of the Franks included much of France and western Germany. Out of this vast territory would emerge the Carolingian empire (with both French and German territories) in the 700s and the Holy Roman Empire in the 900s.

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

TIMELINE OF GERMAN HISTORY:

Week 2: Tue., Oct. 12, 2021

Germanicus

WEEK 2

The most dramatic and memorable chapter in the relationship between Rome and Germany took place in the first century BC-AD during the lifetime of the Roma general Germanicus. The name was a nickname given to him by his troops and the Roman public who adored him. Germanicus' own campaigns in Germany made him famous after avenging the defeat at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (9 BC) and retrieving two of the three legionary eagles that had been lost during the battle. Beloved by the people, he was widely considered to be the perfect Roman long after his death. The Roman people for centuries would consider him as Rome's Alexander the Great due to the nature of his death at a young age, his virtuous character, his dashing physique and his military renown. His place in the imperial family is visible in the chart below. He was the son of Drusus and Antonia. Antonia was the daughter of Mark Anthony and Augustus' sister Octavia. Drusus and his brother Claudius were royalty. And so was the brilliant young man "Germanicus."

The most dramatic and memorable chapter in the relationship between Rome and Germany took place in the first century BC-AD during the lifetime of the Roma general Germanicus. The name was a nickname given to him by his troops and the Roman public who adored him. Germanicus' own campaigns in Germany made him famous after avenging the defeat at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (9 BC) and retrieving two of the three legionary eagles that had been lost during the battle. Beloved by the people, he was widely considered to be the perfect Roman long after his death. The Roman people for centuries would consider him as Rome's Alexander the Great due to the nature of his death at a young age, his virtuous character, his dashing physique and his military renown. His place in the imperial family is visible in the chart below. He was the son of Drusus and Antonia. Antonia was the daughter of Mark Anthony and Augustus' sister Octavia. Drusus and his brother Claudius were royalty. And so was the brilliant young man "Germanicus."

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

Week 3: Tue., Oct. 19, 2021

The Franks

WEEK 3

The Franks (Latin: Franci) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire. Later the term was associated with Romanized Germanic dynasties within the collapsing Western Roman Empire, who eventually commanded the whole region between the rivers Loire and Rhine. They imposed power over many other post-Roman kingdoms and Germanic peoples. Still later, Frankish rulers were given recognition by the Catholic Church as successors to the old rulers of the Western Roman Empire. Although the Frankish name does not appear until the 3rd century, at least some of the original Frankish tribes had long been known to the Romans under their own names, both as allies providing soldiers, and as enemies. The new name first appears when the Romans and their allies were losing control of the Rhine region. The Franks were first reported as working together to raid Roman territory. However, from the beginning the Franks also suffered attacks upon them from outside their frontier area, by the Saxons, for example, and as frontier tribes they desired to move into Roman territory, with which they had had centuries of close contact.

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

Week 4: Tue., Oct. 26, 2021

Saint Boniface and German Christians

WEEK 4

Saint Boniface, "The Apostle to the Germans" was not a German. He came from a little Devon town in southern England. He studied at a monastery close by and in the early 700s went to the Continent to share the Christian teaching with the still unconverted Franks and Belgians. He preached in the northern areas of present day Belgium, the Netherlands and northern Germany with extraordinary success and is still seen as the man who turned Germany to Christianity. He was martyred in 754 in Frisia by bandits who expected to find riches among the travelers possessions. The body of Boniface was taken to the church in Fulda where he remains to this day. Boniface was important in three ways for Germany. First, he organized the growing German church. Through his efforts to reorganize and regulate the church of the Franks, he helped shape the Latin Church in Europe, and many of the dioceses he proposed remain today. He also helped shape the doctrine and practices of the German church to bring it into conformity with the teaching of the Vatican. Most important of all, he was the creator of the alliance between the Papacy and the Carolingian dynasty. This alliance was going to bring into existence the Holy Roman Empire, one of the dominant institutions of the Middle Ages. See below, a Medieval Illuminated book illustration that shows Boniface baptizing and Boniface being murdered.

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

Week 5: Tue., Nov. 2, 2021

The Carolingians

WEEK 5

The Carolingian dynasty was a Frankish noble family founded by Charles Martel with origins in the Arnulfing and Pippinid clans of the 7th century AD. The dynasty consolidated its power within the Frankish political class in Tours, the capital of the Kingdom, during the 700s. In 751 the older Frankish Merovingian dynasty which had ruled the Germanic Franks for several hundred years, was overthrown with the consent of the Papacy, and the Frankish aristocracy. And Pepin the Short, son of Charles Martel, was crowned King of the Franks. The Carolingian dynasty reached its peak in 800 with the crowning of Pepin's son, Charles the Big, Charlemagne, as the first "Emperor of Romans" in the West in over three centuries. He was crowned in Rome by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day, 800. His death in 814 began an extended period of fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire and decline that would eventually lead to the evolution of a new kingdom in the West called the Kingdom of France, and another new institution in German lands called The Holy Roman Empire, which as Voltaire remarked: "was neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire." You might remember that wonderful witty line as you plunge into the complexity of the Holy Roman Empire, since Voltaire was both very funny and very correct. The HRE (a nice abbreviation) really was a German institution driven by German medieval politics for about 700 years.

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

Einhard,

The Life of Charlemagne,

Ann Arbor Paperbacks,

ISBN 047206035X

ABOUT THIS BOOK:

Vita Karoli Magni (Life of Charles the Great) is a biography of Charlemagne, King of the Franks and Holy Roman Emperor, written by Einhard. Historians have traditionally described the work as the first example of a biography of a European king. The author endeavored to imitate the style of that of the ancient Roman biographer Suetonius, most famous for his work the Twelve Caesars. Einhard's biography is especially modeled after the biography of Emperor Augustus, the first emperor of the Roman Empire. The date of the work is uncertain and a number of theories have been put forward. The inclusion of Charlemagne's will at the end of the work makes it fairly clear that it was written after his death in 814. The first reference to the work, however, comes in a letter to Einhard from Lupus of Ferrieres which is dated to the mid-ninth century. Dates have been suggested ranging from about 817 to 833, usually based on interpretations of the text in the political context of the first years of the reign of Louis the Pious and Louis' attitude to his father. Einhard's book is about intimate glimpses of Charlemagne's personal habits and tastes. He occupied favoured position at Charlemagne's court so he had inside information. Einhard received advanced schooling at the monastery of Fulda sometime after 779. Here he was an exceptional student and was quite knowledgeable. The word was sent to Charlemagne of Einhard's expertise. He was then sent to Charlemagne’s Palace School at Aachen in 791. Einhard then received employment at Charlemagne's Frankish court about 796. He remained at this position for twenty some years. Einhard's book was expressly intended to convey his appreciation for advanced education. He wrote his biography after he had left Aachen and was living in Seligenstadt. Einhard's position while with Charlemagne was that of a modern day minister of public works, so he had intimate knowledge of his court. Einhard was also given the responsibility of many of Charlemagne's abbeys.

This is the source of all our knowledge of Charlemagne written by someone who knew him. It is a small book, easy to read, and a small gem. Go get it.

RECOMMENDED READING

If you would like the very best biography of Charlemagne, here it is, new and from our own University of California Press. It is in the Institute library. We are open all day all week if you was to borrow this or any other book.

Janet Nelson,

King and Emperor: A New Life of Charlemagne,

University of California Press; First Edition (September 17, 2019),

ISBN 0520314204

Editorial Reviews

Review

"A deeply learned and humane portrait . . . Nelson’s King and Emperor brings alive the age of Charlemagne, the ruler usually associated with the first effort after the fall of Rome to unite Europe under a single rule. This 'new life' is a bold book. . . . Each chapter is a masterclass in tracing specific bodies of evidence back to the persons or incidents from which they arose. . . . King and Emperor is a masterpiece of historical writing and a robust step toward filling the gap in our historical imagination left by the passing of Rome."

, New York Review of Books

"Janet Nelson assembles an astonishingly rich picture from the most unrewarding of texts. The way she puzzles out probable facts and motivations, based on a complete reading of the existing texts, is a joy to witness. She draws on and shows off the clever work of earlier historians, while giving short shrift to their more biased assumptions. The narrative voice emerges as that of a patient, inquisitive, incisive and helpful master detective, with funny asides, a beautiful style and sensible politics."

, Times Literary Supplement

""There have been countless studies of Charlemagne in many languages...but few have been as ambitiously biographical as Nelson’s. Historians of early medieval Europe are trained to interpret scattered clues and fragments, however, and Nelson is one of the very best."

, London Review of Books

"King and Emperor takes on the compelling suspense of good detective work as well as good history. . . . Janet L. Nelson comes as close as one can to approaching this extraordinary man."

, Wall Street Journal

Week 6: Tue., Nov. 9, 2021

The Ottonians

WEEK 6

In the period after the death of Charlemagne in 814, the successive generations of his sons and grandsons were unable to hold the empire together. Similar territories within the Roman Empire had required hundreds of years to become well integrated into an international empire. And the Carolingians had tried to do it all in just three. In the next 200 years, the slow disintegration produced a myriad of small states, dukedoms, bishoprics etc. that developed their own histories and institutions. For 200 years there wsa no unity and no one dominant German family. Then in the late 900s, the Ottonians emerged. The Ottonian dynasty (German: Ottonen) was a Saxon dynasty of German monarchs(919–1024), named after three of its kings and Holy Roman Emperors named Otto, especially its first Emperor Otto I. It is also known as the Saxon dynasty after the family's origin in the German duchy of Saxony. When this very strong new dynasty of the Ottonians emerged around the late 900s (Otto I, II, III) the choice of the king/emperor had already evolved into an election within which the seven most powerful states chose the next emperor. Therefore, the complex electoral process of choosing the new emperor emerged and remained right to the end of the Empire when Napoleon essentially ended it in 1806.

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

Week 7: Tue., Nov. 16, 2021

Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II

WEEK 7

Frederick II (26 December 1194 – 13 December 1250) was King of Sicily from 1198, King of Germany from 1212, King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor from 1220 and King of Jerusalem from 1225. He was the son of emperor Henry VI of the Hohenstaufen dynasty and of Constance, heiress to the Norman kings of Sicily. His political and cultural ambitions were enormous as he ruled a vast area, beginning with Sicily and stretching through Italy all the way north to Germany. As the Crusades progressed, he acquired control of Jerusalem and styled himself its king. However, the Papacy became his enemy, and it eventually prevailed. Viewing himself as a direct successor to the Roman emperors of antiquity, he was Emperor of the Romans from his papal coronation in 1220 until his death; he was also a claimant to the title of King of the Romans from 1212 and unopposed holder of that monarchy from 1215. As such, he was King of Germany, of Italy, and of Burgundy. At the age of three, he was crowned King of Sicily as a co-ruler with his mother, Constance of Hauteville, the daughter of Roger II of Sicily. His other royal title was King of Jerusalem by virtue of marriage and his connection with the Sixth Crusade. Frequently at war with the papacy, which was hemmed in between Frederick's lands in northern Italy and his Kingdom of Sicily (the Regno) to the south, he was excommunicated three times and often vilified in pro-papal chronicles of the time and after. Pope Gregory IX went so far as to call him an Antichrist. Speaking six languages (Latin, Sicilian, Middle High German, Langues d'oïl, Greek and Arabic, Frederick was an avid patron of science and the arts. He played a major role in promoting literature through the Sicilian School of poetry. His Sicilian royal court in Palermo, beginning around 1220, saw the first use of a literary form of an Italo-Romance language, Sicilian. The poetry that emanated from the school had a significant influence on literature and on what was to become the modern Italian language. He was also the first king to formally outlaw trial by ordeal, which had come to be viewed as superstitious. After his death his line did not survive, and the House of Hohenstaufen came to an end. Furthermore, the Holy Roman Empire entered a long period of decline during the Great Interregnum from which it did not completely recover until the reign of Charles V, 250 years later. (Wikipedia)

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

NEXT WEEK THANKSGIVING BREAK

NO CLASSES ALL WEEK

Week 8: Tue., Nov. 30, 2021

Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII

WEEK 8

Henry VII (German: Heinrich; c. 1278–August 24, 1313) was the King of Germany(or Rex Romanorum) from 1308 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1312. He was the first emperor of the House of Luxembourg. During his brief career he reinvigorated the imperial cause in Italy, which was racked with the partisan struggles between the divided Guelf and Ghibelline factions, and inspired the praise of Dino Compagni and Dante Alighieri. He was the first emperor since the death of Frederick II in 1250, ending the Great Interregnum of the Holy Roman Empire; however, his premature death threatened to undo his life's work. His son, John of Bohemia, failed to be elected as his successor, and there was briefly another anti-king, Frederick the Fair contesting the rule of Louis IV. (Wikipedia)

Henry met Dante in Pisa in 1311. Dante's alto Arrigo

Henry is the famous alto Arrigo in Dante's Paradiso, in which the poet is shown the seat of honor that awaits Henry in Heaven. Henry in Paradiso xxx.137f is "He who came to reform Italy before she was ready for it". Dante also alludes to him numerous times in Purgatorio as the savior who will bring imperial rule back to Italy, and end the inappropriate temporal control of the Church. Henry VII's success in Italy was not lasting, however, and after his death the anti-imperial forces regained control.

The map below shows you the lands held by Henry VII of Luxembourg. As you can see, his family holdings were very sparse within German territories. He added Bohemia through marriage. He hoped to expand his power, by using his role as Holy Roman Emperor to go into Italy and grow his power by adding Italian cities to his empire. This brought him face to face with an implacable foe: Florence.

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

Week 9: Tue., Dec. 7, 2021

Germany and the Black Death

WEEK 9

The Black Death hit all European countries in 1348. Italy was first, with sailors arriving in Sicily early in the year carrying the plague. Then it moved to the mainland and then it moved north and over the Alps to Germany and the rest of northern Europe. The experience of the plague in Germany was unique. In Germany, especially in the Rhineland, hysteria about the plague manifested itself in a unique outbreak of anti-Semitism. In many ways this explosion of hatred of the Jews would not be repeated with this degree of intensity until the 20th century. From Wikipedia: "Renewed religious fervor and fanaticism bloomed in the wake of the Black Death. Some Europeans targeted "various groups such as Jews, friars, foreigners, beggars, pilgrims", lepers, and Romani, blaming them for the crisis. Lepers, and others with skin diseases such as acne or psoriasis, were killed throughout Europe. Because 14th-century healers and governments were at a loss to explain or stop the disease, Europeans turned to astrological forces, earthquakes, and the poisoning of wells by Jews as possible reasons for outbreaks. Many believed the epidemic was a punishment by God for their sins, and could be relieved by winning God's forgiveness. There were many attacks against Jewish communities. In the Strasbourg massacre of February 1349, about 2,000 Jews were murdered. In August 1349, the Jewish communities in Mainz and Cologne were annihilated. By 1351, 60 major and 150 smaller Jewish communities had been destroyed. During this period many Jews relocated to Poland, where they received a warm welcome from King Casimir the Great."

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832

RECOMMENDED READING

John Kelly,

The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death,

Harper Pennial paperback, 2005,

ISBN 0060006935

REVIEW:

Amazon.com Review. A book chronicling one of the worst human disasters in recorded history really has no business being entertaining. But John Kelly's The Great Mortality is a page-turner despite its grim subject matter and graphic detail. Credit Kelly's animated prose and uncanny ability to drop his reader smack in the middle of the 14th century, as a heretofore unknown menace stalks Eurasia from "from the China Sea to the sleepy fishing villages of coastal Portugal [producing] suffering and death on a scale that, even after two world wars and twenty-seven million AIDS deaths worldwide, remains astonishing." Take Kelly's vivid description of London in the fall of 1348: "A nighttime walk across Medieval London would probably take only twenty minutes or so, but traversing the daytime city was a different matter.... Imagine a shopping mall where everyone shouts, no one washes, front teeth are uncommon and the shopping music is provided by the slaughterhouse up the road." Yikes, and that's before just about everything with a pulse starts dying and piling up in the streets, reducing the population of Europe by anywhere from a third to 60 percent in a few short years. In addition to taking readers on a walking tour through plague-ravaged Europe, Kelly heaps on the ancillary information and every last bit of it is captivating. We get a thorough breakdown of the three types of plagues that prey on humans; a detailed account of how the plague traveled from nation to nation (initially by boat via flea-infested rats); how floods (and the appalling hygiene of medieval people) made Europe so susceptible to the disease; how the plague triggered a new social hierarchy favoring women and the proletariat but also sparked vicious anti-Semitism; and especially, how the plague forever changed the way people viewed the church. Engrossing, accessible, and brimming with first-hand accounts drawn from the Middle Ages, The Great Mortality illuminates and inspires. History just doesn't get better than that. --Kim Hughes

Week 10: Tue., Dec. 14, 2021

The Council of Constance

WEEK 10

The Council of Constance took place in the lovely lakeside city of Constance in the Cathedral of Constance. The international church council was the most important church council since the Council of Nicaea in 325 presided over by Emperor Constantine. The issue at Constance was the unity of the Church. The Roman Catholic Church was in tatters by 1400. During the 14th century, the church had found itself with two popes and then later with three. Two popes is one too many popes. The whole church knew by the late 1390s that somehow the Roman Christian church had to find a way back to unity. Thus was called a church council in Constance. Constance was a choice that attempted to satisfy both Northern European countries as well as the very important Italians. It was really "German" in a sense with German language population and a location on the edge of Germanic territories; it was French in the sense that much of the Swiss territories spoke French; and it was Italian with close ties to all the northern Italian Lake District cities and city states. The council's main purpose was to end the Papal schism which had resulted from the confusion following the Avignon Papacy. Pope Gregory XI's return to Rome in 1377, followed by his death (in 1378) and the controversial election of his successor, Pope Urban VI, resulted in the defection of a number of cardinals and the election of a rival pope based at Avignon in 1378. After thirty years of schism, the rival courts convened the Council of Pisa seeking to resolve the situation by deposing the two claimant popes and electing a new one. The council claimed that in such a situation, a council of bishops had greater authority than just one bishop, even if he were the bishop of Rome. Though the elected Antipope Alexander V and his successor, Antipope John XXIII (not to be confused with the 20th-century Pope John XXIII), gained widespread support, especially at the cost of the Avignon antipope, the schism remained, now involving not two but three claimants: Gregory XII at Rome, Benedict XIII at Avignon, and John XXIII. Therefore, many voices, including Sigismund, King of the Romans and of Hungary (and later Holy Roman Emperor), pressed for another council to resolve the issue. That council was called by John XXIII and was held from 16 November 1414 to 22 April 1418 in Constance, Germany

REQUIRED READING

Steven Ozment,

A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People,

Harper Perennial,

ISBN 0060934832