American Gigolo

American Gigolo (USA, 1980)

Director and Writer: Paul Schrader

(Blue Collar, Hardcore, Affliction, Forever Mine)

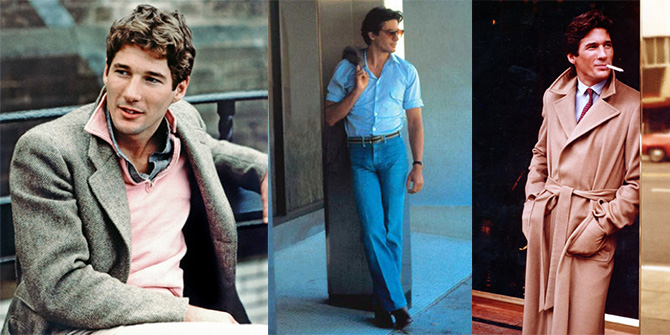

Cast: Richard Gere, Luren Hutton, Hector Elizondo, Nina Van Pallandt

From Roger Ebert:

“American Gigolo” is a stylish and surprisingly poignant handling of this material. The experiences in the film may be alien to us, but the emotions of the characters are not: Julian Kay, the gigolo of the title, is played by Richard Gere as tender, vulnerable, and a little dumb. We care about him. His business — making love to rich women of a certain age — allows him to buy the baubles by which Beverly Hills measures success, and he has his Mercedes, his expensive wardrobe, his antique vases, his entree to country clubs.

But he says he’s in business for reasons other than money, and we believe him, if only because he hardly seems to value his possessions as anything other than props. He feels a sense of satisfaction when he makes a middle-aged woman happy, he says. He seems to see himself as a cross between a sexual surrogate and a therapist, and the movie does, too: Why, he’s hardly a whore at all, not even counting his heart of gold. The movie sentimentalizes on this point, setting up the character of Julian Kay as so sympathetic that we forgive him his profession. That’s a tactic that “American Gigolo”‘s writer and director, Paul Schrader, is borrowing from one of his own heroes, the French director Robert Bresson, whose “Pickpocket” makes a criminal into an antihero. Schrader is setting the stage for the key relationship in the film, between Julian and the senator’s wife (Lauren Hutton). He tries to pick her up in an exclusive restaurant, but breaks off their conversation when he decides she’s not a likely client. But she is all too likely, and tracks him down to his apartment. They fall in love, at about the time he’s being framed for the murder of a Palm Springs socialite, and the movie wants us to believe in the power of love to redeem both characters: Julian learns to love unselfishly, without money, and the woman learns to love honestly, without regard for her husband’s position. This business of redemption would work better if “American Gigolo” had at least a few more scenes developing the relationship between Gere and Hutton: Her character, so central to the movie’s upbeat conclusion, isn’t seen clearly enough. We aren’t shown the steps by which she moves from sex to love. We aren’t given enough detail about their feelings. That’s a weakness, but not a fatal one, because when Schrader cuts away from their relationship, it’s to develop a very involving story about the murder, the framing, and the police investigation. The movie has an especially effective performance by Hector Elizondo as a cigar-chomping vice detective who cheerfully admits he thinks Gere is guilty as sin. The whole movie has a winning sadness about it; take away the story’s sensational aspects and what you have is a study in loneliness. Richard Gere’s performance is central to that effect, and some of his scenes — reading the morning paper, rearranging some paintings, selecting a wardrobe — underline the emptiness of his life. We leave “American Gigolo” with the curious feeling that if women weren’t paying this man to sleep with them, he’d be paying them: He needs the human connection and he has a certain shyness, a loner quality, that makes it easier for him when love seems to be just another deal.